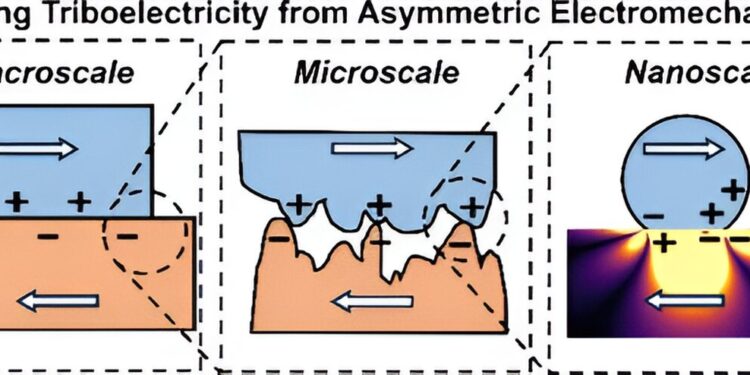

Graphic summary. Credit: Nano Letters (2024). DOI: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.4c03656

Anyone who has ever petted a cat or dragged their feet across a carpet knows that the friction of objects generates static electricity. But the explanation for this phenomenon has eluded researchers for more than two millennia.

Now, scientists at Northwestern University have finally discovered the mechanisms at work.

Researchers have discovered that when an object slides, the front and back of the object experience different forces. This difference in forces causes different electrical charges to accumulate on the front and back of the object. And the difference in electrical charges creates a current, which causes a light discharge.

The study was published in the journal Nano Letters.

“For the first time, we are able to explain a mystery that no one could solve before: why friction matters,” said Laurence Marks of Northwestern, who led the study.

“People have tried, but they have failed to explain the experimental results without making assumptions that were neither justified nor justifiable. Now we can, and the answer is surprisingly simple. Simply having different deformations—and therefore different charges—at the front and back of a sliding object causes current to form.”

Marks, a surface structure specialist, is professor emeritus of materials science and engineering at Northwestern’s McCormick School of Engineering. Karl Olson, a doctoral student in Marks’ research group, is the paper’s first author.

The Greek philosopher Thales of Miletus first reported friction-induced static electricity in 600 BC. After rubbing amber with fur, he noticed that the fur attracted dust.

“It has since become clear that friction induces static charge in all insulators, not just fur,” Marks said. “However, that’s more or less where the scientific consensus ends.”

Marks and his team began to unravel the mystery in 2019. In a study published in Physical Exam LettersThey found that rubbing two materials against each other causes tiny protrusions on the surface of the materials to bend. These bent and deformed protrusions give rise to stresses, the researchers discovered.

“In 2019, we had an idea of what was going on. However, like all seeds, it took time for it to grow,” Marks said. “Now it has flowered. We have developed a new model that calculates the electric current. The current values for a series of different cases agreed well with the experimental results.”

The concept of “elastic shear” is at the heart of the new model. Elastic shear can occur when a material resists a sliding force. If a person pushes a plate across a table, the plate will resist sliding. As soon as the person stops pushing, the plate stops moving. This extra friction, caused by the sliding resistance, causes the electric charges to move.

“Sliding and shear are intimately related,” Marks said.

Static electricity can cause some fun mishaps, like your hair standing on end after sliding down a slide, but it can also cause serious problems. For example, sparks from static electricity cause industrial fires and even explosions. It can also interfere with the consistent dosing of powdered pharmaceuticals. By better understanding the mechanisms at play, researchers could potentially come up with new solutions to these problems.

“Static electricity affects life in ways that are both simple and profound,” Marks said. “The static charge on coffee beans has a major influence on how coffee beans are ground and how they taste. Earth probably wouldn’t be a planet without a key step in the aggregation of particles that form planets, which occurs because of the static electricity generated by the collision of beans. It’s amazing how much of our lives are affected by static electricity and how much the universe depends on it.”

More information:

Karl P. Olson et al., What Puts the “Tribo” in Triboelectricity?, Nano Letters (2024). DOI: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.4c03656

Provided by Northwestern University

Quote: Why Petting Your Cat Causes Static Electricity (2024, September 18) retrieved September 19, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.