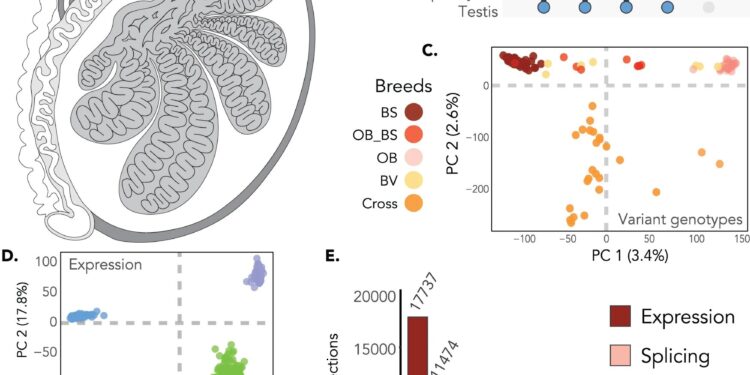

Overview of the molQTL cohort for three male reproductive tissues. A The three male reproductive tissues used in our study and the number of samples considered for each tissue. B Swatches overlap between fabric types. The height of the bar represents the number of individuals. The fabrics are colored as in (A)). VS PCA of sequence variant genotypes of 366,090 uncorrelated variants, with colors corresponding to the breed assigned by the Swiss herdbook Braunvieh or Cross. BV = Braunvieh; BS = Brown Swiss; OB = original BV; BS_OB = Crossing between BS and OB; Crossbreed = Crossbreeding between OB or BS and another breed. D Scatterplot of the two main PCA components of normalized expression values (TPM; upper panel) and normalized splicing phenotypes (PSI; lower panel) for all tissues. The fabrics are colored as in A). E Overlap of expressed and spliced genes in the three tissues (based on TPM and PSI matrices). Credit: Natural communications (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-44935-7

Infertility is a widespread problem: worldwide, one in eight couples fail to realize their desire to have children within a year, if at all. In half of cases, this is due to male fertility disorders. However, it is difficult to identify the genetic causes of these fertility disorders in men. Researchers lack data on sperm quality and molecular markers from sufficiently large cohorts of healthy men of reproductive age.

The path to a better understanding of the genes and mechanisms that control male fertility therefore passes through appropriate laboratory animals, in this case bulls.

A research team led by Hubert Pausch, professor of animal genomics at ETH Zurich, studied young bulls to study in detail which genes are active in different tissues of the animals’ reproductive organs and how this affects their fertility. Their study was recently published in the journal Natural communications.

For this investigation, researchers from the Institute of Agricultural Sciences used samples of testicles, epididymis and vas deferens from 118 freshly slaughtered bulls of reproductive age. The animals were not killed specifically for research.

One thing the scientists characterized using these biopsies was the bulls’ transcriptome, that is, all the messenger RNAs present in each tissue type, which represent the gene transcripts. This allowed the team to discover which genes are active in which of the three tissues. Based on this knowledge, they created corresponding transcriptome profiles for the bulls. They then compared these profiles with those of humans and mice.

Through this research, the team discovered a large number of genes and their variants associated with fertility in bulls. Most of the genes discovered are also likely to be relevant to male fertility in humans. In evolutionary terms, the regulation of male fertility is “highly conserved,” explains Xena Mapel, first author of the study. This means that the genes responsible for reproduction work the same way in mammals.

“These genes are closely linked to low fertility in bulls,” says Mapel. “Such subfertile bulls do not appear during conventional ejaculate screening. However, they can be reliably detected using our new marker genes.”

Unusual animal model

Although cattle are an unusual choice of animal model, they are ideal for such studies. On the one hand, the genes of breeding bulls are well understood, and on the other hand, breeding organizations obtain ejaculation from animals twice a week as part of their normal operations. This is analyzed in detail before being diluted and used to inseminate hundreds of cows – or is thrown away if the quality of the ejaculate is poor.

The cohort of bulls analyzed here also has the great advantage that all animals are the same age. “This cohort is very homogeneous. If we were to carry out a comparable study on men, we would have to rely on voluntary donors, potentially in all possible age groups. This would give us very difficult data to compare.”

Data on the fertility of young men are collected every year from Swiss recruits to the armed forces, but they can hardly be used for such analyses. “We do not know what influences the men were exposed to before taking the fertility test, which will be different for each test subject. Additionally, it is virtually impossible to obtain tissue samples from their reproductive tract, as this would involve an invasive medical procedure.”

Findings for the benefit of breeders

It is not yet clear how these new findings will be integrated into human fertility research, but they are already paving the way for better diagnostics to identify corresponding genes and their variants in breeding bulls. This means that breeders will likely be the first to benefit from the results, as they will help minimize financial losses due to failed artificial inseminations.

Currently, the quality of each bull’s ejaculate is tested before use and the calves’ genome is analyzed; however, some infertile bulls still escape. If a breeder inseminates cows with semen from an infertile bull, the cows will not become pregnant.

And since each insemination costs 80 Swiss francs, this can quickly eat up a breeder’s budget: a typical Swiss dairy farm spends several thousand Swiss francs per year to artificially inseminate its herd of cows. But it doesn’t stop there: unsuccessfully inseminated cows often cause other problems for farmers, because they don’t give birth to calves and no longer produce milk, forcing the farmer to replace them. And it costs money.

Artificial insemination is now the norm in beef and dairy cattle breeding, as well as pig farming. In Switzerland, around 800,000 cows are artificially inseminated each year. Natural matings – when a bull mates naturally with a cow – occur very rarely. “Raising a bull is not easy. Most farmers don’t have space for such a large animal,” says Pausch.

More information:

Xena Marie Mapel et al, Molecular quantitative trait loci in reproductive tissues impact male fertility in cattle, Natural communications (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-44935-7

Quote: What can bulls tell us about men? Genetic discovery could translate into human fertility research (February 16, 2024) retrieved February 16, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.