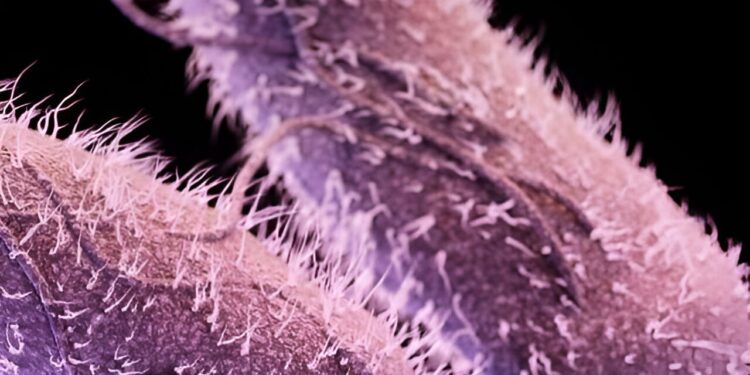

Salmonella Baildon, shown here in large format, is a rare type of Salmonella, reported in less than 1% of cases nationwide over five years. Researchers found it in wastewater from the plants studied and confirmed that one reported case came from a person who lived in the catchment area of one of the plants. Credit: CDC

First used in the 1940s to monitor polio, wastewater surveillance has proven to be such a powerful disease surveillance tool that the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) created the National Wastewater Surveillance System to support SARS-CoV-2 surveillance in September 2020. Now, a team of scientists from Penn State and the Pennsylvania Department of Health has shown that monitoring household wastewater is also useful for a foodborne pathogen.

In the results published on September 19 in the Journal of Clinical MicrobiologyResearchers report that Salmonella enterica bacteria were detected in samples from two central Pennsylvania wastewater treatment plants in June 2022.

“Nontyphoidal salmonella is a common cause of gastroenteritis worldwide, but current disease surveillance is suboptimal. In this research, we evaluated the utility of wastewater surveillance to improve surveillance for this foodborne pathogen,” said Nkuchia M’ikanatha, chief epidemiologist for the Pennsylvania Department of Health and an affiliated researcher in the Department of Food Science at Penn State University’s College of Agricultural Sciences.

“In this study, we investigated wastewater surveillance as a tool to improve surveillance of this foodborne pathogen. Wastewater testing can detect traces of infectious diseases circulating in a community, even in asymptomatic individuals, providing an early warning system for potential outbreaks.”

Although health care professionals are required to report cases of salmonellosis, many cases go unnoticed. Salmonella bacteria, found in the intestines of animals and humans, are excreted in feces. The CDC estimates that salmonella is responsible for approximately 1.35 million infections, 26,500 hospitalizations, and 420 deaths per year in the United States, primarily through contaminated food.

In June 2022, the researchers analyzed raw wastewater samples collected twice weekly from two treatment plants in central Pennsylvania for nontyphoidal Salmonella and characterized the isolates using whole genome sequencing. They recovered 43 Salmonella isolates from the wastewater samples, which were differentiated by genomic analysis into seven serovars, which are groupings of microorganisms based on similarities. Eight of the isolates, or nearly 20%, were from a rare type of Salmonella called Baildon.

The researchers analyzed raw wastewater samples collected twice weekly from two treatment plants in central Pennsylvania for nontyphoidal Salmonella and characterized the isolates using whole genome sequencing. They recovered 43 Salmonella isolates from the wastewater samples. Credit: Ed Dudley.

The researchers assessed the genetic relatedness and epidemiological links between nontyphoidal Salmonella isolates from wastewater and similar bacteria from patients with salmonellosis. The Salmonella Baildon serovars isolated from wastewater were genetically indistinguishable from a similar bacterium found in a patient associated with a salmonellosis outbreak during the same period in the region.

Salmonella Baildon in wastewater and in the national outbreak detection database, 42 outbreak-related isolates had the same genetic composition. One of the 42 outbreak-related isolates was obtained from a patient residing in the wastewater sample catchment area, which serves approximately 17,000 people.

Salmonella Baildon is a rare serovar, reported in less than 1% of cases nationally over five years, noted M’ikanatha, the study’s first author. He noted that this research demonstrates the value of monitoring wastewater in a defined population to complement traditional surveillance methods to detect evidence of Salmonella infections and determine the extent of outbreaks.

“Using whole genome sequencing, we showed that isolates of the Salmonella Baildon variant clustered with those from an outbreak that occurred in a similar time period,” he said.

“The reported cases were primarily from Pennsylvania, and one individual lived within the catchment area of the treatment plant. This study supports the use of domestic wastewater surveillance to help public health agencies identify communities affected by infectious diseases.”

Ed Dudley, a professor of food science and the study’s lead author, said the findings highlight the potential of wastewater monitoring as an early warning system for foodborne illness outbreaks, potentially before doctors and labs even report cases. This proactive approach could allow health officials to quickly trace the source of contaminated food, reducing the number of people affected, suggested Dudley, who also directs Penn State’s E. coli Reference Center.

“While it may not happen overnight, I foresee a future where many, if not most, domestic wastewater treatment plants will provide samples of raw sewage to monitor for signs of various diseases,” he said. “This would likely involve collaboration between public health agencies, academia and federal entities, similar to our pilot study. I see this as another critical lesson from the pandemic.”

More information:

Nkuchia M. M’ikanatha et al., Salmonella Baildon associated with outbreak found in wastewater demonstrates how wastewater surveillance can complement traditional disease surveillance, Journal of Clinical Microbiology (2024). DOI: 10.1128/jcm.00825-24

Provided by Pennsylvania State University

Quote: Wastewater monitoring can detect foodborne illness, researchers say (2024, September 20) retrieved September 20, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.