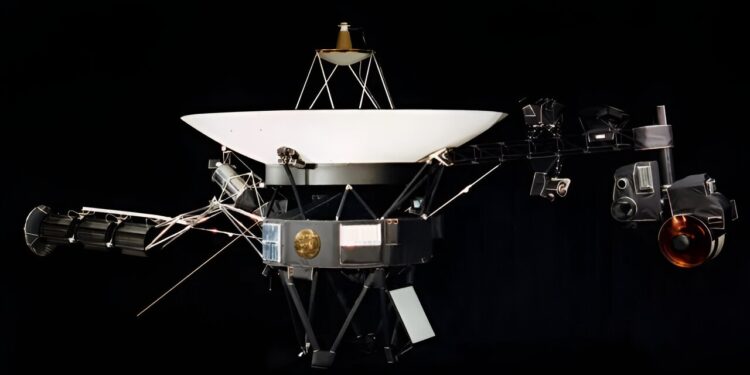

A model of NASA’s Voyager spacecraft. The twin Voyager probes have been flying since 1977, exploring the outer regions of our solar system. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Engineers working on NASA’s Voyager 1 probe have successfully fixed a problem with the spacecraft’s thrusters, which keep the deep-sea explorer pointed toward Earth so it can receive commands, send engineering data and provide the unique scientific data it collects.

After 47 years, a fuel tube inside the thrusters became clogged with silicon dioxide, a byproduct that appears over time from a rubber diaphragm in the spacecraft’s fuel tank. The clog reduces how efficiently the thrusters can generate force. After weeks of careful planning, the team replaced the spacecraft with another set of thrusters.

The thrusters are powered by liquid hydrazine, which is converted to gas and released in bursts lasting a few tens of milliseconds to gently tilt the spacecraft’s antenna toward Earth. If the clogged thruster were in good condition, it would fire about 40 of these short pulses a day.

Both Voyager probes are equipped with three thruster groups: two attitude thruster groups and one trajectory correction maneuvering thruster group. During the mission’s planetary flybys, the two types of thrusters were used for different purposes. But because Voyager 1 is following an unchanged trajectory out of the solar system, its thruster requirements are simpler, and either thruster group can be used to point the spacecraft toward Earth.

In 2002, the mission engineering team, based at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, noticed that some fuel tubes in the attitude thruster branch used for pointing were clogged. So the team switched to the second branch. When that branch showed signs of obstruction in 2018, the team switched to the trajectory-correction maneuvering thrusters and has been using that branch ever since.

Now, those trajectory correction thruster tubes are even more clogged than the original branches were when the team swapped them out in 2018.

The clogged tubes are located inside the thrusters and direct fuel to the catalyst beds, where it is converted to gas. (These tubes are different from the fuel tubes that send hydrazine to the thrusters.) While the tube opening was originally only 0.01 inch (0.25 millimeters) in diameter, the obstruction reduced it to 0.0015 inch (0.035 mm), or about half the width of a human hair. As a result, the team had to revert to one of the thruster branches for attitude propulsion.

Warming up the thrusters

The thruster swap would have been a relatively simple operation for the mission in 1980 or even 2002. But the age of the spacecraft introduced new challenges, primarily related to power and temperature. The mission turned off all nonessential systems on board, including some heaters, on both spacecraft to preserve their gradually diminishing power supplies, generated by plutonium decay.

While these measures reduced power consumption, they also caused the spacecraft to cool down, an effect compounded by the loss of other non-essential systems that produced heat. As a result, the legs of the attitude thrusters became cold, and operating them in this state could damage them, rendering the thrusters unusable.

The team decided that the best option would be to warm up the thrusters before making the switch by turning on the heating elements that were considered nonessential. However, as with many challenges the Voyager team faced, this solution presented a problem: The spacecraft’s electrical power is so low that turning on the nonessential heating elements would require the mission to turn off something else to provide the heating elements with enough power, and whatever is currently running is considered essential.

After studying the issue, they ruled out turning off any of the still-functioning science instruments for a limited time, because there is a risk that the instrument might not turn back on. After additional study and planning, the engineering team determined that they could safely turn off one of the spacecraft’s main heaters for an hour, freeing up enough energy to turn on the thruster heaters.

It worked. On August 27, they confirmed that the necessary thruster branch was back in action, helping to steer Voyager 1 toward Earth.

“Any decisions we have to make in the future will require much more analysis and caution than before,” said Suzanne Dodd, Voyager project manager at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, which manages Voyager for NASA.

The probes explore interstellar space, the region outside the bubble of particles and magnetic fields created by the Sun, where no other spacecraft are expected to go for a long time. The mission’s science team is working to keep the Voyager probes operating for as long as possible, so they can continue to reveal what the interstellar environment is like.

Quote: Voyager 1 Crew Completes Delicate Thruster Swap (2024, September 11) Retrieved September 11, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.