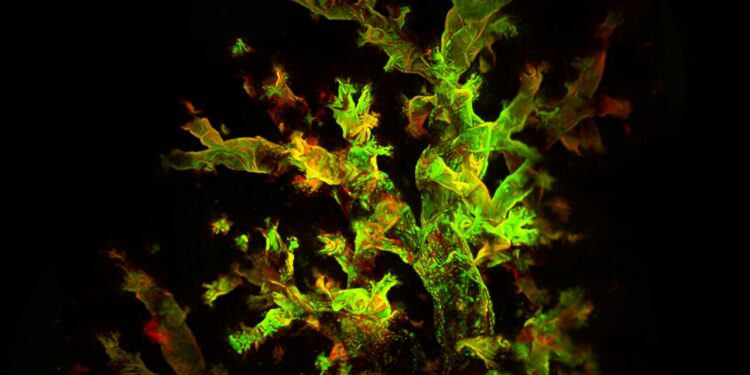

A 3D reconstruction of a mouse lung four days after infection with fluorescent Sendai virus reveals widespread viral presence (red) and active replication (green). A study by WashU Medicine researchers shows that respiratory viruses can hide in immune cells in the lungs long after the first symptoms of an infection have subsided, creating a persistent inflammatory environment that promotes the development of chronic lung diseases such than asthma. Credit: Italo Araujo Castro

Doctors have long known that children who become seriously ill from certain respiratory viruses such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) are at high risk of developing asthma later in life. What they don’t know is why.

A new study by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis may have solved the mystery. The study, conducted in mice, shows that respiratory viruses can hide in immune cells in the lungs long after the first symptoms of an infection have disappeared, creating a persistent inflammatory environment that favors the development of lung disease. . Additionally, they showed that eliminating infected cells reduced signs of chronic lung damage before it progressed into full-blown chronic respiratory disease.

The results, published in Natural microbiologypoint to a potential new approach to preventing asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and other chronic lung diseases by eradicating the persistent respiratory viruses that fuel these conditions.

“Currently, children who have been hospitalized for a respiratory infection such as RSV are sent home once their symptoms resolve,” said lead author Carolina B. López, professor of molecular microbiology and researcher at the BJC at WashU Medicine. “To reduce the risk of these children developing asthma, in the future we may be able to check whether all the virus has actually disappeared from the lungs and remove any lingering viruses before sending them home.”

In the United States, approximately 27 million people have asthma. Many factors influence a person’s likelihood of developing a chronic respiratory disease, including living in a neighborhood with poor air quality, being exposed to cigarette smoke, and being hospitalized for a viral pneumonia or bronchitis at a young age.

Some researchers, including López, suspected that the link between severe lung infection and subsequent diagnosis of asthma was due to a persistent virus in the lungs that causes continued damage, but a direct link between the continued presence of the virus and a Chronic lung disease has not been previously demonstrated. .

López and first author Ítalo Araújo Castro, a postdoctoral researcher in his lab, developed a unique system involving a naturally occurring mouse virus known as Sendai virus and fluorescent markers of infection. Sendai is linked to the human parainfluenza virus, a common respiratory virus that, like RSV, has been linked to asthma in children. Sendai behaves in mice similarly to the human parainfluenza virus in humans, making it an excellent model of the types of infections that can lead to chronic lung disease.

Using the fluorescent trackers, the researchers were able to observe signs of the virus throughout the infection. After about two weeks, the mice recovered, but viral RNA and proteins were still detectable several weeks later in their lungs, hidden in immune cells.

“The discovery of a virus persisting in immune cells was unexpected,” López said. “I think that’s why it was missed before. Everyone was looking for viral products in the epithelial cells that line the surface of the respiratory system, because that’s where these viruses primarily replicate. But they found in immune cells.

Additionally, the presence of the virus altered the behavior of infected immune cells, making them more inflammatory than uninfected immune cells. Persistent inflammation sets the stage for the onset of chronic lung disease, the researchers said.

Indeed, seven weeks after infection, the lungs of the mice showed inflammation of the air sacs and blood vessels, abnormal development of lung cells and excess immune tissue, all signs of chronic inflammatory lung damage, although the mice apparently appeared to have recovered. Once the infected immune cells were cleared, signs of damage diminished.

“We use a highly matched virus-host pairing to demonstrate that a common respiratory virus can be maintained in immunocompetent hosts much longer than the acute phase of infection, and that this viral persistence can lead to chronic lung disease,” Castro said. “The long-term health effects we see in people thought to be recovering from acute infection are likely due to the persistence of the virus in their lungs.”

The findings suggest new ways of thinking about preventing chronic lung disease, the researchers said.

“Almost all children are infected with these viruses before the age of 3, and perhaps 5% of them get illness severe enough that they can develop a persistent infection,” López said. “We won’t be able to prevent children from becoming infected in the first place. But if we understand how these viruses persist and the effects of that persistence on the lungs, we may be able to reduce the risk of serious long-term problems. term.”

More information:

Ítalo Araújo Castro et al, Murine parainfluenza virus persists in innate immune cells of the lungs, supporting chronic lung pathology, Natural microbiology (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41564-024-01805-8

Provided by Washington University in St. Louis

Quote: Viruses discovered hiding in lung immune cells long after initial illness (October 2, 2024) retrieved October 2, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.