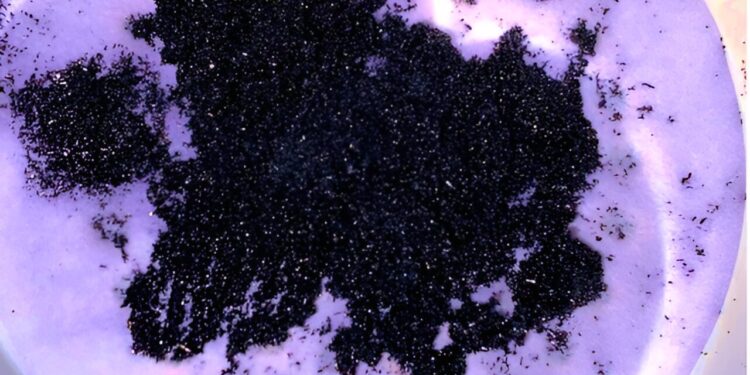

Vanadium, one of the CO2 capturing materials, displaying a brilliant dark purple color. Credit: May Nyman, professor of chemistry, OSU College of Science

A chemical element so visually striking that it is named after a goddess exhibits a “Goldilocks” level of reactivity—not too much, not too little—that makes it a strong candidate as a carbon-scavenging tool.

The element is vanadium, and research by scientists at Oregon State University, published in Chemical sciencedemonstrated the ability of vanadium peroxide molecules to react with and bind carbon dioxide, an important step toward improved technologies for removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

The study is part of a $24 million federal effort to develop new methods for direct air capture, or DAC, of carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas produced by the burning of fossil fuels and associated with climate change.

Facilities that filter carbon from the air have started popping up around the world, but they are still in their infancy. Technologies to mitigate carbon dioxide at the point of entry into the atmosphere, such as in power plants, are more developed. Both types of carbon capture will likely be necessary if Earth is to avoid the worst consequences of climate change, scientists say.

In 2021, Oregon State’s May Nyman, the Terence Bradshaw Professor of Chemistry in the College of Science, was selected as the leader of one of nine direct air capture projects funded by the Department of Energy. His team studies how certain transition metal complexes can react with air to remove carbon dioxide and convert it to metal carbonate, similar to what is found in many natural minerals.

Transition metals are located near the center of the periodic table and their name comes from the transition of electrons from low energy states to high energy states and vice versa, giving rise to distinctive colors. For this study, scientists landed on vanadium, named after Vanadis, the ancient Norse name for the Scandinavian goddess of love, considered so beautiful that her tears turned to gold.

Nyman explains that carbon dioxide exists in the atmosphere at a density of 400 parts per million. This means that for every 1 million air molecules, 400 of them are carbon dioxide, or 0.04%.

“A challenge with direct capture of air is finding sufficiently selective molecules or materials, otherwise other reactions with more abundant air molecules, such as reactions with water, will override the reaction with the CO.2“, Nyman said. “Our team has synthesized a series of molecules containing three important parts for removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, and they work together.”

Some of it was vanadium, so named because of the range of beautiful colors it can exhibit, and some of it was peroxide, which bonded with the vanadium. Because a vanadium peroxide molecule is negatively charged, it needs alkali cations to balance the charges, Nyman said, and the researchers used alkaline cations of potassium, rubidium and cesium for this study.

She added that the collaborators also tried to replace vanadium with other metals in the same vicinity in the periodic table.

“Tungsten, niobium and tantalum were not as effective in this chemical form,” Nyman said. “On the other hand, molybdenum was so reactive that it sometimes exploded.”

Additionally, scientists replaced the alkalis with ammonium and tetramethylammonium, the former being slightly acidic. These compounds didn’t react at all, a puzzle that researchers are still trying to understand.

“And when we removed the peroxide, again, there wasn’t a lot of reactivity,” Nyman said. “In this sense, vanadium peroxide is a beautiful purple goldilocks that turns gold when exposed to air and binds a carbon dioxide molecule.”

She notes that another attractive characteristic of vanadium is that it allows a relatively low release temperature of around 200°C for the captured carbon dioxide.

“This compares to almost 700°C when bonded to potassium, lithium or sodium, other metals used for carbon capture,” she said. “Being able to re-release the captured CO2 allows for the reuse of carbon capture materials, and the lower the temperature required to do this, the less energy is needed and the lower the cost. Some very clever ideas regarding the reuse of captured carbon are already being implemented, for example by routing captured CO through pipelines.2 in a greenhouse to grow plants.

Other Oregon State authors listed on the paper included Tim Zuehlsdorff, assistant professor of theoretical/physical chemistry, and postdoctoral researcher Eduard Garrido.

“I am also very proud of the hard work of the graduate students in my lab, Zhiwei Mao and Karlie Bach, as well as Taylor Linsday,” Nyman said. “This is a completely new area for my lab, as well as for Tim Zuehlsdorff, who supervised doctoral student Jacob Hirschi on computational studies aimed at explaining reaction mechanisms. Starting a new area of study involves many unknowns.”

More information:

Eduard Garrido Ribó et al, Implementation of vanadium peroxides as materials for direct capture of carbon in the air, Chemical science (2023). DOI: 10.1039/D3SC05381D

Provided by Oregon State University

Quote: Vanadium research makes key advances in capturing carbon from the air (February 12, 2024) retrieved February 12, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.