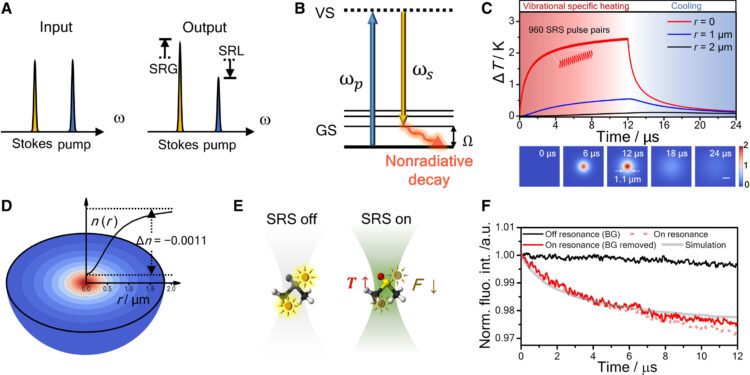

Theoretical simulation and experimental observation of the SRP effect.(A) Schematic of stimulated Raman gain and loss. (B) Schematic of the SRP effect. (VS) Simulation of the temperature rise induced by the SRP in the temporal (top) and spatial (bottom) domains. Spatial scale bar, 1 μm. (D) Simulated thermal lens profile induced by SRP in pure DMSO. (E) Illustration of the measurement by a fluorescence thermometer of the temperature increase mediated by the SRP. (F) Fluorescence intensity of rhodamine B in DMSO during an SRS process. The beat frequency (ωp − ωs) is set to 2913 cm−1 for resonance and 2850 cm−1 for off-resonance (BG). The resonance curve (BG removed) is obtained by subtracting the resonance off (BG) from the resonance curve to eliminate non-photothermal contributions. BG, background; au, arbitrary units. Credit: Scientists progress (2023). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adi2181

When microscopes struggle to pick up weak signals, it’s like trying to spot subtle details in a painting or photograph without your glasses. For researchers, this makes it difficult to detect small things happening in cells or other materials. In new research, Dr. Ji-Xin Cheng, Moustakas Professor of Photonics and Optoelectronics at Boston University, and his collaborators are creating more advanced techniques to allow microscopes to better see the small details of samples without the need for special dyes.

Their results, published in Natural communications And Scientists progress respectively, help scientists visualize and understand their samples more easily and accurately.

In this Q&A, Dr. Cheng, who is also a professor in several departments at BU (Biomedical Engineering, Electrical and Computer Engineering, Chemistry and Physics), delves deeper into the results discovered in the two research articles. It highlights the work he and his team currently have in progress and provides a comprehensive understanding of how these discoveries could impact the field of microscopy and, potentially, influence future scientific applications.

You and your research collaborators recently published two articles on microscopy in Natural communications And Scientists progress. What are the main conclusions of each article?

These two papers aim to address a fundamental challenge in the emerging field of vibrational imaging that opens a new window for life sciences and materials science. The challenge is how to push the detection limit so that vibrational imaging is as sensitive as fluorescence imaging so that we can visualize target molecules at very low concentrations (micromolar to nanomolar) without dye.

Our innovation to address this fundamental challenge is to deploy photothermal microscopy to detect chemical bonds in a sample. After the vibrations of the chemical bond are excited, the energy quickly dissipates as heat, causing a rise in temperature. This photothermal effect can be measured by a probe beam passing through the focal point.

Our method is fundamentally different from coherent Raman scattering microscopy, a high-speed vibrational imaging platform described in my 2015 scientific review. Together, we have created a new class of chemical imaging toolkit, called photothermal microscopy vibrational, or VIP microscopy.

In the Natural communications In this paper, we developed a wide-field mid-infrared photothermal microscope to visualize the chemical content of a viral signal particle. In the Scientists progress paper, we developed a new vibrational photothermal microscope based on the stimulated Raman process.

Were there any unexpected or surprising results in either article? If so, how do these results challenge existing knowledge or theories around microscopy?

The development of SRP microscopy was unexpected. We never believed that the Raman effect was powerful enough for photothermal microscopy, but our ideas changed in August 2021. To celebrate my 50th birthday, my students and I threw a sports-themed party. During the festivities, Yifan Zhu, the first author of Scientists progress paper, unfortunately suffered an injury, leading his doctor to recommend a two-month period of reduced mobility.

During his convalescence, I asked him to perform a calculation of the temperature rise at the focus of an SRS (stimulated Raman scattering) microscope. Thanks to this accident, we discovered a strong stimulated photothermal Raman (SRP) effect. Yifan and other students then dedicated two years to development. This is how SRP microscopy was invented.

Did the articles identify any limitations or gaps in their findings? How might these limitations impact the overall implications of the research?

Of course, nothing is perfect. Continuing SRP microscopy, we found that each beam can have absorption, which causes a weak non-Raman background in the SRP image. We are developing a new way to remove this background.

Do the findings of one article complement or contradict those of the other? How do they relate to each other?

The methods reported in these two articles are complementary. The WIDE-MIP method is suitable for detecting IR active bonds, while the SRP method is sensitive to Raman active bonds.

Do the articles suggest new directions for future microscopy research that could have significant long-term implications?

Yes indeed. Together, these two papers indicate a new class of chemical microscopy called vibrational photothermal microscopy or VIP microscopy. VIP microscopy offers a very sensitive way to probe specific chemical bonds; we can thus use them to map molecules of very low concentrations without dye labeling.

Are these imaging technologies currently available or used by other researchers outside of your laboratory?

We have filed provisional patents for both technologies through the BU Technology Development Office. At least two companies are interested in commercializing SRP technology and one of them is also interested in WIDE-MIP technology.

Who are your main research collaborators?

In the WIDE-MIP article, virus samples are provided by John Connor, associate professor of microbiology at BU’s National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories. The development of WIDE-MIP technology is carried out in collaboration with Selim Ünlü, professor of electrical and computer engineering at BU’s College of Engineering. This is therefore a collaborative work within Boston University.

More information:

Qing Xia et al, Fingerprinting a single virus by mid-infrared photothermal microscopy enhanced by wide-field interferometric defocusing, Natural communications (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-42439-4

Yifan Zhu et al, Photothermal Raman microscopy stimulated towards ultrasensitive chemical imaging, Scientists progress (2023). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adi2181

Provided by Boston University

Quote: Q&A: Unveiling a new era of imaging: engineers conduct revolutionary microscopy techniques (December 4, 2023) retrieved December 5, 2023 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.