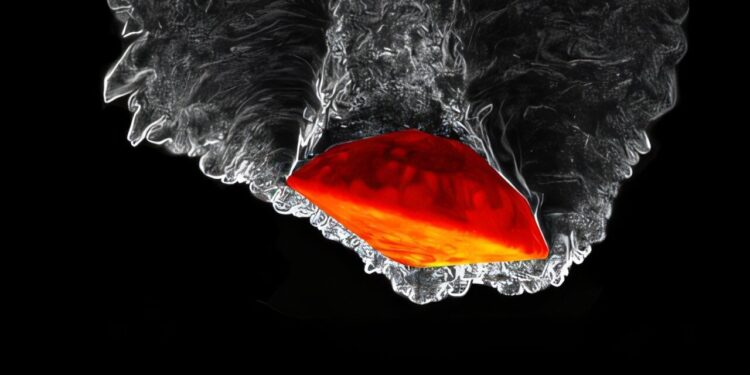

A high-fidelity simulation of the flow around the Mars Science Laboratory entry vehicle in the Martian atmosphere (data provided by Antón-Álvarez, A. and A. Lozano-Durán, Physical Review Fluids). The ray scale shading shows the magnitude of the vortex, while the red color map indicates the wall temperature. Yuan and Lozano-Durán’s new dimensionless learning framework was used to create a model that estimates surface heat flux for entry vehicles in this class. Credit: Antón-Álvarez, A. and A. Lozano-Durán, Physical Review Fluids

Machine learning models are designed to integrate data, find patterns or relationships within that data, and use what they learn to make predictions or create new content. The quality of these results depends not only on the details of a model’s internal workings, but also, and more importantly, on the information that feeds the model.

Some models follow a brute force approach, essentially adding all the data related to a particular problem into the model and seeing what comes out. But a more elegant and less energy-intensive way to approach a problem is to determine which variables are vital to the outcome and provide the model with information about only those key variables.

Now Adrián Lozano-Durán, associate professor of aerospace at Caltech and visiting professor at MIT, and Yuan Yuan, an MIT graduate student, have developed a theorem that takes a number of possible variables and reduces them, leaving only those that are most important. In doing so, the model removes all units, such as meters and feet, from the underlying equations, making them dimensionless, which is what scientists require of equations that describe the physical world. The work can be applied not only to machine learning but to any mathematical model.

“The theorem we derived will tell you, even for a set of inputs that have dimensions, how to construct dimensionless inputs that contain the maximum amount of information about what you want to predict,” says Lozano-Durán. “It will also tell you the percentage error on the best possible prediction you can make with this information.”

Lozano-Durán and Yuan describe their new method in an article published in the journal Natural communications.

According to Lozano-Durán, for many physical models, it is possible to have a set of thousands or even millions of variables linked in one way or another to a prediction you want to make. But not all of these variables will be equally useful in making a prediction.

Consider the problem of predicting tomorrow’s temperature in Pasadena. A model for this problem could include thousands of variables, from measurements of barometric pressure and wind speed at multiple times and locations, to readings of temperatures above the sea from ocean buoys, to satellite measurements of water vapor.

Now suppose you also decide to include the driver’s license numbers of every driver in California. These numbers represent more data for the model to take into account: a lot of data. But that has nothing to do with the question of what the weather will be like tomorrow.

The example may seem silly, but it clearly shows what the new method aims to do: remove variables that don’t contain information that will help a model make the best possible prediction.

“Why aren’t all license numbers useful for predicting the temperature tomorrow? Because they don’t contain any information about the temperature. And that’s the key,” says Lozano-Durán. “When we add input variables, there is hidden information about what you want to predict, and that information is what you need to extract. The quality of your prediction is related to how much information your input contains about your output.”

Lozano-Duran and Yuan call their new method IT-π, where IT stands for information theory, on which the method is built. For a given variable, the method calculates how much information in the output can be obtained from that input. IT-π represents the relationship between input and output in the form of a Venn diagram, where the input is one circle and the output another.

The method seeks to determine the extent to which these circles overlap for each variable. If there is no overlap, there is no prediction. If they completely overlap, the input fully predicts the output. The method combines the variables in different ways and measures the overlap for each of these scenarios, ultimately achieving the highest possible overlap.

“When we can no longer increase the overlap, the method has found the best possible variables,” explains Lozano-Durán.

In the new paper, Lozano-Durán and Yuan use the new method to make various predictions. In one example, they wanted to determine which inputs to feed into a neural network used to calculate heat flow (how much the temperature experienced by a space capsule would change) upon entry into the Martian atmosphere. The researchers had access to data on 20 different variables that could be included, such as speed and temperature at different locations.

Ultimately, their analysis dictated that they only needed data combined into two variables constructed as characteristic flux ratios, such as heat and mass, or other physical terms such as energies and time scales. These variables capture the relative importance of competing processes.

No unit needed

It is important to note, Lozano-Durán notes, that the variables that emerge from his new theorem are dimensionless. There is a fundamental mathematical concept in physics called Buckingham’s π theorem which says that when you build a model about the real world, you should be able to rewrite all of its equations in a form where none of the variables depend on the units of measurement used. Edgar Buckingham, the early 20th century American physicist after whom the theory is named, provided a formalized way of transforming equations to arrive at such so-called dimensionless parameters.

“All equations in physics must follow this property. If you change the units, the equation stays the same,” says Lozano-Durán. For example, the gravitational force between the Earth and the sun should not depend on whether the distance between the two bodies is measured in miles or kilometers, or whether the masses are measured in pounds or kilograms. “If you see an equation where you change the units and the equation is different, there is something wrong.”

Returning to the Lozano-Durán Martian spacecraft example, Buckingham’s π theorem says that seven variables, instead of two, are needed to determine heat flow. According to Lozano-Durán, a researcher would need to perform some 2,000 experiments to gather the required data for these seven variables and create a very simple model of heat flow.

“According to our results, nine experiments are enough,” he says. The tool also told the researchers that by performing these nine experiments, they could have 92% confidence that they had arrived at the correct prediction of heat flow.

The IT-π method can save time, energy and money, he says. In particular, the technique could reduce the amount of data needed to train AI models faster while using less electricity.

“Today, especially in these machine learning models that are kind of a big black box, it’s very important to make sure that whatever you’re feeding them makes sense,” he says. “The more variables you have as input, the more training data you need. So you want to have the minimum number of variables without affecting the performance of your model.”

More information:

Yuan Yuan et al, Dimensionless information-based learning, Natural communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-64425-8

Provided by California Institute of Technology

Quote: Unitless theorem identifies key variables for AI and physics models (October 29, 2025) retrieved October 30, 2025 from

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.