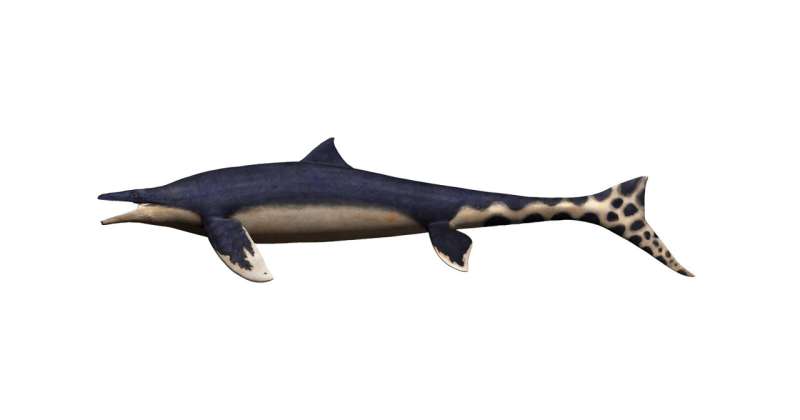

The wakayama soryu (blue dragon) was a mosasaur the size of a great white shark that lived 72 million years ago off the coast of what is now Japan. Credit: TAKUMI

Researchers have described a Japanese mosasaur the size of a great white shark that terrorized the seas of the Pacific 72 million years ago.

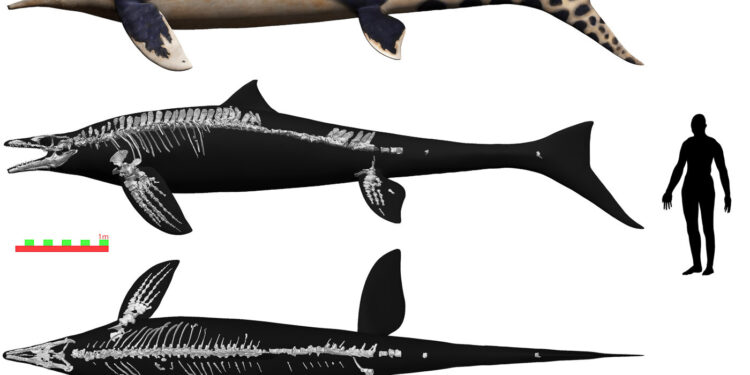

Extra-long tail fins could have facilitated propulsion in concert with its long finned tail. And unlike other mosasaurs, or large extinct marine reptiles, it had a shark-like dorsal fin that would have helped it turn quickly and precisely in the water.

University of Cincinnati associate professor Takuya Konishi and his international co-authors described the mosasaur and placed it in a taxonomic context. Journal of Systematic Paleontology.

The mosasaur is named after the place where it was found, Wakayama Prefecture. Researchers call it Wakayama Soryu, meaning blue dragon. Dragons are legendary creatures in Japanese folklore, Konishi said.

“In China, dragons make thunder and live in the sky. They became aquatic in Japanese mythology,” he explained.

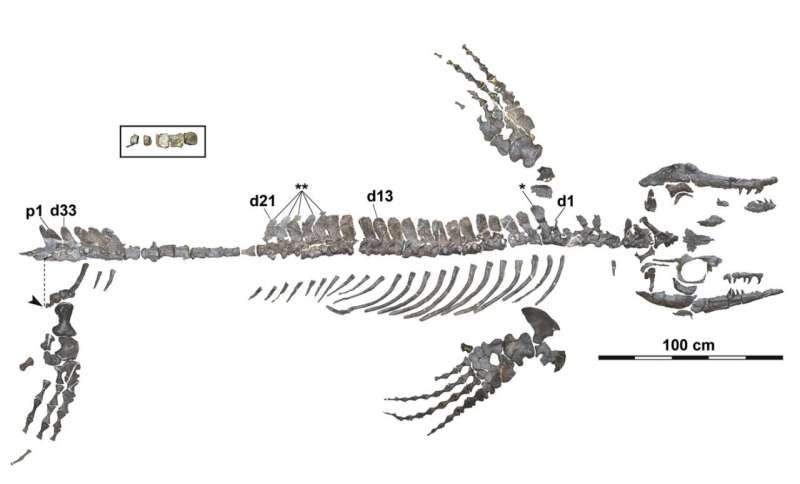

The specimen was discovered along the Aridagawa River in Wakayama by co-author Akihiro Misaki in 2006. Misaki was searching for invertebrate fossils called ammonites when he found a dark and intriguing fossil in the sandstone, a Konishi said.

Misaki continued to search for ammonites before curiosity got the better of him and he returned to the dark bone. Closer examination revealed that it was a vertebra, part of a nearly complete mosasaur captured in the hard sandstone.

The specimen is the most complete mosasaur skeleton ever found in Japan or the Pacific Northwest, Konishi said.

“In this case, it was almost the entire specimen, which was astounding,” Konishi said.

He devoted his career to the study of these ancient marine reptiles. But the Japanese specimen has unique characteristics that defy simple classification, he said. Its rear flippers are longer than the front ones. These enormous fins are even longer than its crocodile-shaped head, unique among mosasaurs.

“I thought I knew them pretty well by now,” Konishi said. “Immediately, it was something I had never seen before.”

A mosasaur discovered in Japan was the most complete skeleton ever discovered in Japan or the Pacific Northwest. Credit: Takuya Konishi

Mosasaurs were apex predators in prehistoric oceans from about 100 million years ago to 66 million years ago. They were contemporaries of Tyrannosaurus rex and other late Cretaceous dinosaurs that ruled the Earth. Mosasaurs fell victim to the same mass extinction that killed almost all the dinosaurs when an asteroid hit what is now the Gulf of Mexico.

The Wakayama Soryu has some features similar to mosasaurs found in New Zealand and other features comparable to mosasaurs found in California, he said.

It had almost binocular vision that would have made it a deadly hunter, he said.

The researchers placed the specimen in the subfamily Mosasaurinae and named it Megapterygius wakayamaensis to recognize where it was found. Megapterygius means “large wings”, in keeping with the enormous fins of the mosasaur.

Konishi said these large, paddle-shaped fins could have been used for locomotion. But this type of swimming would be extraordinary not only in mosasaurs but in virtually all other animals.

Another prehistoric marine reptile called a plesiosaur used its flippers to propel itself, but it did not have a long, rudder-like tail, he explained.

“We lack a modern analogue with this type of body morphology, from fish to penguins to sea turtles,” he said. “None have four large flippers that they use in conjunction with a caudal fin.”

The researchers hypothesized that the large front fins might have facilitated rapid maneuvering, while its large rear fins might have provided lean for diving or surfacing. And presumably, like other mosasaurs, its tail would have generated a powerful and rapid acceleration when it hunted fish.

“The question is how these five hydrodynamic surfaces were used. Which ones were for steering? Which ones for propulsion?” he said. “This opens up a whole can of worms that challenges our understanding of how mosasaurs swim.”

The Wakayama Soryu (blue dragon) was a great white shark-sized mosasaur with a dorsal fin and long flippers. Credit: Takumi

Unique to mosasaurs, the Wakayama Soryu apparently had a dorsal fin, based on the orientation of the neural spines along its vertebrae. The orientation of these spines is remarkably similar to that of a harbor porpoise, which also has a prominent dorsal fin, according to the study.

“This remains hypothetical and speculative to some extent, but this distinct change in the orientation of the neural column behind a presumed center of gravity is consistent with today’s toothed whales having dorsal fins, like dolphins and porpoises,” he said.

A team of researchers spent five years removing the surrounding sandstone matrix from the fossils. They also took a cast of the mosasaur in place to provide a record of the skeletal orientation of the bones before their excavation.

More information:

Takuya Konishi et al, A new derived mosasaurine (Squamata: Mosasaurinae) from southwest Japan reveals unexpected postcranial diversity among hydropedic mosasaurs, Journal of Systematic Paleontology (2023). DOI: 10.1080/14772019.2023.2277921

Provided by the University of Cincinnati

Quote: This Japanese “dragon” terrorized the ancient seas (December 12, 2023) retrieved on December 12, 2023 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.