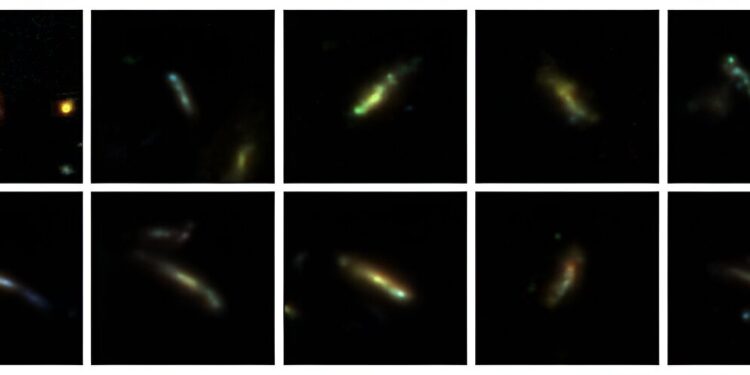

Images of what researchers believe to be elongated, ellipsoid (i.e. breadstick-shaped) galaxies captured with the James Webb Space Telescope. The word “believe” reflects the fact that some galaxies may be disc-shaped (i.e. pizza pie) galaxies when viewed from the side. Credit: Viraj Pandya et al.

Columbia researchers analyzing images from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope have found that galaxies in the early universe are often flat and elongated, like breadsticks, and rarely round, like balls of pizza dough.

“About 50 to 80 percent of the galaxies we’ve studied appear flattened in two dimensions,” said Viraj Pandya, a NASA Hubble researcher at Columbia University and lead author of a new paper that will appear in The Astrophysics Journal which presents the results. The article is currently published on the arXiv preprint server.

“Galaxies that look like long, thin breadsticks appear to be very common in the early universe, which is surprising since they are rare among galaxies in the current universe.”

The team focused on a large field of near-infrared images provided by Webb, known as the Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science (CEERS) survey, removing galaxies that are estimated to have existed when the universe was between 600 million and 6 billion years old.

While most distant galaxies look like breadsticks, others are shaped like pizza pies or balls of pizza dough. “Pizza dough balls,” or sphere-shaped galaxies, appear to be the smallest type of galaxy and have also been the least frequently identified. The pizza pie-shaped galaxies were found to be as large as breadstick-shaped galaxies along their longest axis. “They are more common in the nearby universe, which, due to its continued expansion, is composed of older, more mature galaxies.”

Which category would our galaxy, the Milky Way, fall into if we could go back in time several billion years? “Our best guess is that it might have looked more like a breadstick,” said co-author Haowen Zhang, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Arizona in Tucson. This hypothesis is based in part on new evidence from Webb: theorists have “gone back in time” to estimate the mass of the Milky Way billions of years ago, suggesting that it would likely have been shaped like ‘a breadstick in the distant past.

These distant galaxies are also much less massive than nearby spiral and elliptical galaxies: they are the precursors of more massive galaxies like ours. “In the early universe, galaxies had much less time to develop,” said co-author Kartheik Iyer, a NASA Hubble Fellow also at Columbia University.

“Identifying additional categories for early galaxies is exciting – there is much more to analyze now. We can now study the relationship between galaxy shape and appearance and better project how they formed in much more detail.”

Hubble, the space telescope launched in 1990 and which has collected data to date, “has long shown an excess of elongated galaxies,” said co-author Marc Huertas-Company, a researcher at the Institute of astrophysics of the Canary Islands. But researchers still wondered: Would additional details appear better with the infrared light sensitivity of the Webb telescope, launching in 2021?

“Webb confirmed that Hubble did not miss any additional features in the galaxies they both observed. Additionally, Webb showed us many more distant galaxies with similar shapes, all in great detail,” said Huertas-Company.

One question, of course, is why early galaxies tended to be so flattened and elongated. One hypothesis, Pandya explained, is that the early universe might have been filled with filaments of dark matter that formed a kind of “skeletal background,” or “cosmic highway,” that carried gas and stars along it. These filaments still exist but have become much more diffuse as the universe has expanded, so they may be less likely to support the formation of breadstick-shaped galaxies.

Examples of distant galaxy shapes identified by the James Webb Space Telescope’s Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science (CEERS) survey. Credits: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Steve Finkelstein (UT Austin), Micaela Bagley (UT Austin), Rebecca Larson (UT Austin)

The paper is called “Galaxies Going Bananas,” yet another food analogy that came to the authors’ minds while reviewing their data. When the authors plotted the aspect ratios of the galaxies relative to their longest axis, they found that the resulting diagrams looked distinctly like bananas, a shape that reflects their elongated ellipsoid shape (i.e. -say a breadstick).

“Bananas are another way of saying that these intrinsically elongated galaxies appear to be the dominant galaxies during the first 4 billion years of the universe,” Pandya said.

There are still gaps in our knowledge. Not only do researchers need an even larger sample of Webb to further refine the precise properties and locations of distant galaxies, but they will also need to devote sufficient time to tweaking and updating their models to better reflect the geometry specifies distant galaxies.

“These are early results,” said co-author Elizabeth McGrath, an associate professor at Colby College in Waterville, Maine. “We need to dig deeper into the data to understand what’s happening, but we’re very excited about these early trends.”

More information:

Viraj Pandya et al, Galaxies Going Bananas: Inferring the 3D Geometry of High-Redshift Galaxies with JWST-CEERS, arXiv (2023). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2310.15232

Provided by Columbia University

Quote: Webb data suggests many early galaxies were long and thin, not disk-shaped or spherical (January 17, 2024) retrieved January 18, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.