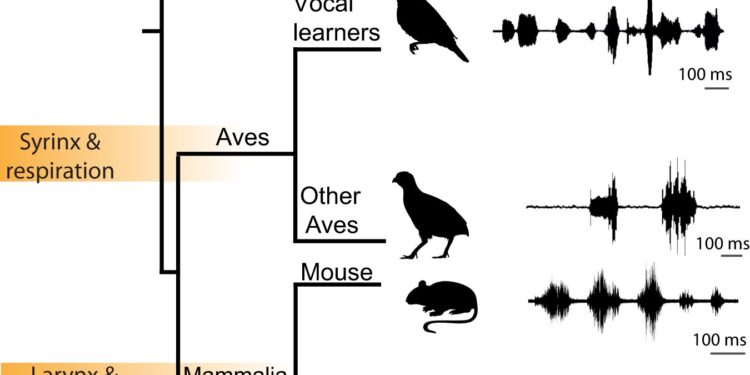

Vocal diversity in fish and tetrapods. Credit: Natural communications (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-43794-y

For talkative midship fish, sometimes called “California singing fish,” the midbrain plays an important role in initiating and structuring the sound trains used in vocal communication.

It turns out that the midbrains of these fish may serve as a useful model for understanding how mammals and other vertebrates, including humans, control vocal expressions, according to Cornell behavioral research published Jan. 2 in Natural communications.

“We have evidence demonstrating how important this part of the brain, the midbrain, is for vocal signaling,” said lead author Andrew Bass, Horace White Professor of Neurobiology and Behavior in the College of Arts and Sciences. “It’s a brain region shared by all vertebrates, whether it’s a fish, a bird or a person, and it is crucial for the patterning and selection of sounds.”

Midshipmen’s fish phrasing takes the form of grunts, grunts and buzzing sounds whenever males seek mates or fend off enemies, Bass said. To the human ear, the buzzing sound may sound like a single note from a French horn or foghorn. While midshipmen live off the coasts of Northern California and the Pacific Northwest during the fall and winter, they head into the shallow intertidal zones to spawning sites in late spring and summer. They are good fathers and guard hundreds of unhatched eggs which develop into free-swimming fry located under rock shelters.

At low tide, people sitting along the shoreline on a calm summer night report the constant, conversational buzz of a chorus of male-sucking fish.

Science knew that mammals and other vertebrates made sounds and vocalized to communicate their behaviors, but the midbrain responsible for initiating acoustic features, like the structured buzzes in these fish or the formation of convincing sentences in humans, had remained largely unexplored.

Eric R. Schuppe, a former Cornell postdoctoral researcher in Bass’s lab who is now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, San Francisco, led the research.

Bass, Schuppe and others in the lab found that periaqueductal gray neurons in the midbrain of fish are activated in distinct patterns by males during mating calls, foraging and nest guarding.

The group confirmed that periaqueductal gray neurons evoke output to muscles that manage the sound and vocal characteristics of courtship, and also show other types of calls.

Communication signals structured by the midbrain “have frequency and amplitude components, and fish string sounds together in different ways,” Bass said. “Perhaps these sounds signify aggression or serve a mating function, like trying to attract a mate to a nest, which is what male midshipmen do with their buzzing.”

The human brain is shaped like a helmet, and the midbrain sits at the top of the brain “stem.” Fish brains are more tube-shaped, making them a more accessible model to study experimentally, Bass said. “Our results now show that fish and mammals share functionally comparable periaqueductal gray nodes that can influence the acoustic structure of social context-specific vocal signals,” he said.

Bass noted that for humans, this research provides clues about what happens if the human midbrain is damaged. He suggested that this research could help us understand how dysfunction in the human midbrain can make a person uncommunicative or mute.

“Only in recent years has the midbrain received more attention from neuroscientists who study social communication,” Bass said. “It is a major node connected to your cortex, basal ganglia, amygdala and hypothalamus. In this way, it acts as a gateway for these sources of executive functions to reach d “other regions of the brain, more directly activating the muscles that underlie behavioral actions.”

“The midbrain is an amazing part of the brain because it shows how essential it is, if you’re a vertebrate, to have the ability to produce sound communication signals. Period.”

More information:

Eric R. Schuppe et al, Midbrain node for context-specific vocalization in fish, Natural communications (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-43794-y

Provided by Cornell University

Quote: California singing fish midbrain may serve as model for how mammals control vocal expressions (January 2, 2024) retrieved January 3, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.