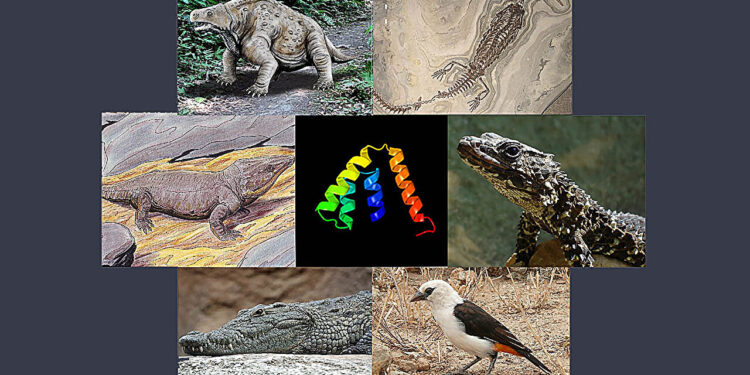

Karn and Laukaitis show that rather than being only mammals, the secretoglobins are also found in turtles, crocodilians, lizards and birds, suggesting that they existed during the carboniferous period. Credit: Bob Karn

At a conference in Washington, DC, in 2000, the super family of proteins secretoglobin was appointed to classify proteins with structural similarities with its founding member of the uteroglobin. Now, 25 years later, it is still little known on the basic functions of these proteins, encouraging researchers at the Carl R. Woese Institute of genomic biology to dive into their evolutionary origins.

This bioinformatics survey reported that secretoglobins, or SCGBS, considered exclusive to mammals – are also found in turtles, crocodilians, lizards and birds. These new discoveries, published in Biology and evolution of genomeSuggest that these proteins have evolved earlier than dinosaurs and share a basic function that is not yet discovered.

“We have a series of SCGB genes within the human genome, but no one knows what their function is,” said Christina Laukaitis (Eirh / Rbte), Associate Professor of Clinique at Carle Illinois College of Medicine.

“If we want to understand, we must understand what we share and do not share with other organizations. We hope that by identifying what other organizations have these genes, we can determine a shared protein function.”

“A first principle of biology is the question of the structure against the function,” said Bob Karn (GNDP), professor in the Department of Biomedical and Translational Sciences at the Carle Illinois College of Medicine. “This is a classic case where we know the structures of the SCGBS, but in most cases, not their functions.”

Although their main biological functions are still unknown, researchers have shown that the SCGB genes that code for SCGB proteins are expressed in secretory epithelial tissues. In addition, the deregulation of these genes can have implications in pulmonary diseases and respiratory tract, kidney disease, inflammation and cancer.

“However, none of these basic functions, but rather what they do in the right circumstances,” said Laukaitis.

The challenge is that SCGBS are mainly studied in the context of human health and diseases and in common model organizations such as mice, rats and rabbits. From this limited point of view, a large part of the story is incomplete, which makes it difficult to determine the basic functions of these proteins.

“No one has looked beyond the mammals, so the fundamental question we ask is whether we can find SCGBS in non-mammals. It was a bioinformatics study of all the genomes available from different groups of organizations to determine who has the different members of this secretoglobin family, essentially a comparative genomic project,” said Laukaitis.

Karn and Laukaitis carried out a deep dive in animal genomes, using bioinformatics methods to search for SCGB genes. Some of the genes identified in the study were previously predicted using information algorithms from the National Biotechnology Center of NIH. However, they have never been organized for their structural characteristics or officially published in the scientific literature.

Using comparative genomics, Karn also discovered new gene sequences by manually using the BLAT tool at the University of California, the browser of the Santa Cruz genome for the alignments of gene sequences, then the creation of SCGB phylogenies.

The overall results of their study were surprising. Not only are SCGBs found beyond mammals, but they have a general presence on different species of turtles, crocodilians, lizards and birds. In addition, the data suggests that the SCGBS evolved in the first amirts 320 million years ago during the carboniferous period, before the dinosaurs roam the earth.

“The secretoglobins seem to be an amniot invention,” said Karn.

AMNIOTA, reptiles that do not need to lay their eggs in the water, is a large group of tetrapods and vertebrate semi-camarades which consists of two main clades: synapsids and sauropside. Humans and other mammals are part of the synapse clade.

“When we returned to amphibians, fish and invertebrates, there was no indication of SCGB genes. So that seems to be a very clear line,” Karn said.

The establishment of the evolutionary origin of these proteins laid the basics of future studies in order to study the basic shared functions of the family of SCGB proteins. One hypothesis that the team has confirmed is that a group of SCGBS plays a role in animal communication.

“This group of SCGBS is called liaison proteins to androgens, or ABP, and they are only in mammals. In our work with mice, we found them only in the facial and neck glands. Since the first thing that rodents do when they meet, Karn said.

“And our other works have shown that they prefer to mate with mice that share their own type of ABP. In other words, they are dumbfounding sexual selection in the population of the mouse.”

In the future, Karn and Laukaitis plan to explore this hypothesis further and hope that overall, their results provide renewed excitement for this area of research.

Karn said: “Many of these SCGBs could be precious for medical problems. Since nobody knows what these little cytokine proteins do, they could very well be involved in something we have to know. The group of evolutionary biologists and geneticians who were heading 25 years ago.

More information:

Robert C Karn et al, a large study of the genome reveals a large presence of secretoglobin genes in the Squamate and Archosaurs reptiles which have flowered in diversity among mammals, Biology and evolution of genome (2025). Doi: 10.1093 / GBE / EVAF024

Supplied by the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign

Quote: The genomic survey discovers the evolutionary origins of secretoglobins (2025, May 5) recovered on May 5, 2025 from

This document is subject to copyright. In addition to any fair program for private or research purposes, no part can be reproduced without written authorization. The content is provided only for information purposes.