Credit: iScience (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.isci.2024.110903

Fans of Clementine, the cat who recently captivated TikTok with her rare eye color, should take note. The piercing golden gaze of cheetahs, the striking blue gaze of snow leopards, and the luminous green glow of leopards are all traits that can be attributed to an ancestor, an ocelot-like feline ancestor that roamed the Earth more recently 30 million years old.

In a new study published in iScienceHarvard researchers say this ancestral population likely included felines with brown and gray eyes, the latter paving the way for the rapid and broad diversification of iris color seen in cat species today.

“When I started this study, I asked, ‘What do we know about eye color?’ “And the truth is that very few, because there are virtually no phylogenetic studies on the evolution of eye color,” said lead author Julius Tabin, a student at the Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in the Department of organic and evolutionary biology.

Most studies focus on the distribution of eye color within a species or the genes involved in creating eye color in humans and domestic animals. Studies of eye color in animal populations are rare due to preservation challenges and lack of diversity: most animals have brown eyes.

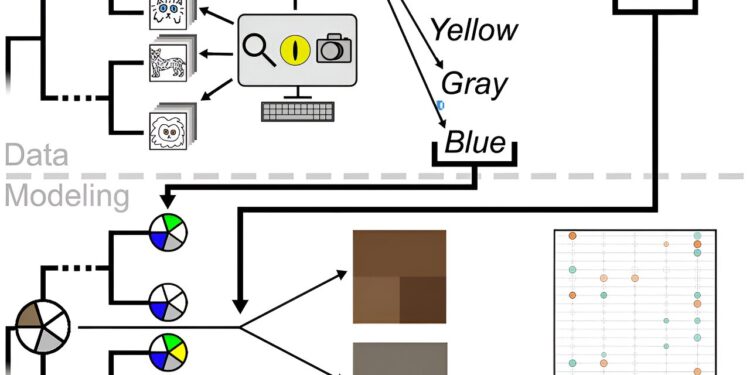

While eye color in humans is likely the result of sexual selection and in domestic animals, artificial selection, Tabin wonders what drove the great diversity of wild felids. With no fossil preservation to rely on, Tabin took a novel approach by analyzing digital images from sources such as iNaturalist to identify and categorize the different eye colors of 52 felid taxa.

Tabin and co-author Katherine Chiasson, a Ph.D. candidate at Johns Hopkins University, created an algorithm to map iris colors onto a phylogenetic tree of felids.

“We found a lot of color variability between species,” Tabin said, “but, surprisingly, we also found a lot of intraspecific variability. Most species have a singular eye color with no variation. So it’s really surprising that once you get into cats (lions, tigers, panthers, etc.) we see all these different eye colors. There are actually very few species of felids that only have. only one eye color in their population.

Equipped with the colors mapped on the phylogenetic tree, the researchers set out to reconstruct the ancestral state. They discovered that early pre-felid lineages (the ancestor of felids and their closest relatives, linsangs) only had brown eyes. However, after the linsang species bifurcated, gray-eyed felines appeared alongside brown-eyed ones.

“It is likely that this is due to a genetic mutation that significantly decreased pigmentation in the eye,” Tabin said. Melanin can be either eumelanin, which is brown, or pheomelanin, which is yellow.

Going from a brown eye to a gray eye would require a decrease in eumelanin. This decrease would lead to an eye that was not entirely brown or entirely gray, but a brownish gray color, which is what the researchers found.

These gray-eyed felines opened the door to a burst of greens, yellows and blues, providing an anchor between brown eyes and the new colors.

“Blue eyes require carefully balanced low levels of pigment and are likely recessive in felids. A wild population would likely not be able to maintain blue eyes in a population with only one blue-eyed individual among a sea brown eyes.

“It’s likely that you would need something lighter than brown, but not as light as blue, to be the mediator. And that’s what you see: in every species of cat with blue eyes, they also have gray eyes,” Tabin said.

Tabin and Chiasson also observed that brown eyes and yellow eyes rarely coexist within a species. They said they were surprised to see a positive correlation between yellow eyes and round pupils, and a negative correlation between brown eyes and round pupils.

The researchers found no significant correlation between activity mode, zoogeographic region, habitat, and eye color uniformity, leaving the adaptive advantage of having varied eye colors a open question to pursue.

The researchers not only reconstructed the general eye color types present at each evolutionary node, but they were also able to predict the exact eye color of each ancestor.

“Being able to quantitatively reconstruct color is one of the paper’s greatest strengths, because it means we are the first animals to see eye color since these felids were alive millions of years ago.” , Tabin said.

For Chiasson, the study was special in part because all of the resources used are available for free online. “The fact that rigorous studies like ours can be carried out by anyone with an Internet connection and a certain curiosity is indicative of a field-wide revolution that increases the accessibility of science in the whole world.”

The study opens the possibility of further research into the evolutionary importance of gray eyes, as well as the evolution of eye color in natural populations, Tabin said. “I’m still very excited to know that the feline ancestor had both brown and gray eyes, because that’s something I didn’t expect or even think about.”

More information:

Julius A. Tabin et al, Evolutionary insights into iris color of Felidae through ancestral state reconstruction, iScience (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.isci.2024.110903

Provided by Harvard University

This story is courtesy of the Harvard Gazette, the official newspaper of Harvard University. For more information about the university, visit Harvard.edu.

Quote: Study traces wild cat eye color diversity to ancient ancestor (October 2, 2024) retrieved October 2, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.