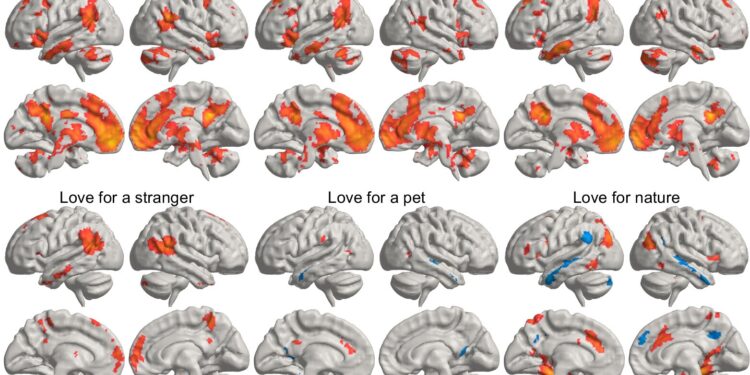

Statistical average of how different types of love light up different brain regions. Credit: Pärttyli Rinne et al 2024, Aalto University.

We use the word “love” in a wide variety of contexts, from sexual adoration to parental love to love of nature. Now, more comprehensive brain imaging may shed light on why we use the same word for such a diverse set of human experiences.

“You see your newborn baby for the first time. The baby is sweet, healthy and strong: it is the greatest wonder of your life. You feel love for this little one.”

This statement is one of several simple scenarios presented to fifty-five parents, who described themselves as being in a romantic relationship. Researchers at Aalto University used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to measure brain activity as the subjects reflected on brief stories related to six different types of love.

“We now have a more complete picture of the brain activity associated with different types of love than previous research,” says Pärttyli Rinne, the philosopher and researcher who coordinated the study. “The activation pattern for love is generated in social situations in the basal ganglia, the midline of the forehead, the precuneus, and the temporo-parietal junction on the sides of the back of the head.”

Love for one’s children generates the most intense brain activity, followed closely by romantic love.

“In parental love, there was a profound activation of the brain’s reward system in the striatum area during the imagination of love, and this was not observed for any other type of love,” Rinne says. Love for romantic partners, friends, strangers, pets, and nature were also part of the study, which was published this week in the journal Cerebral cortex newspaper.

According to research, brain activity is influenced not only by the proximity of the object of love, but also by whether it is a human being, another species or nature.

Unsurprisingly, compassionate love toward strangers is less rewarding and elicits less brain activation than love in close relationships. In contrast, love of nature activates the reward system and visual areas of the brain, but not the social areas of the brain.

Pet owners identifiable through brain activity

The biggest surprise for the researchers was that the brain areas associated with love between people were very similar, with the differences mainly in the intensity of activation. All types of interpersonal love activated brain areas associated with social cognition, while love for animals or nature did not, with one exception.

Subjects’ brain responses to a statement like this reveal, on average, whether or not they share their life with a four-legged friend: “You’re at home, lying on the couch, and your pet cat comes up to you. The cat curls up next to you and purrs sleepily. You love your pet.”

“When looking at love for animals and the brain activity associated with it, the brain areas associated with sociability statistically reveal whether or not the person owns a pet. When it comes to pet owners, these areas are more activated than in people who don’t have pets,” Rinne explains.

Love activations were controlled in the study using neutral stories in which nothing much happened. For example, looking out the bus window or absent-mindedly brushing one’s teeth. After listening to a professional actor’s rendition of each “love story,” participants were asked to imagine each emotion for ten seconds.

This is not the first time Rinne and his team have tried to find love. Their members include researchers Juha Lahnakoski, Heini Saarimäki, Mikke Tavast, Mikko Sams and Linda Henriksson. They have already undertaken several studies aimed at deepening our scientific knowledge of human emotions. The group published a study a year ago mapping subjects’ bodily experiences of love. The previous study also established a link between stronger physical experiences of love and close interpersonal relationships.

Not only can understanding the neural mechanisms of love help guide philosophical discussions about the nature of love, consciousness and human connection, but the researchers also hope their work will improve mental health interventions for conditions such as attachment disorders, depression and relationship problems.

More information:

Pärttyli Rinne et al., Six types of love differently recruit brain areas of reward and social cognition, Cerebral cortex (2024). DOI: 10.1093/cercor/bhae331

Provided by Aalto University

Quote:Finding Love: Study Reveals Where Love Is in the Brain (2024, August 26) retrieved August 26, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.