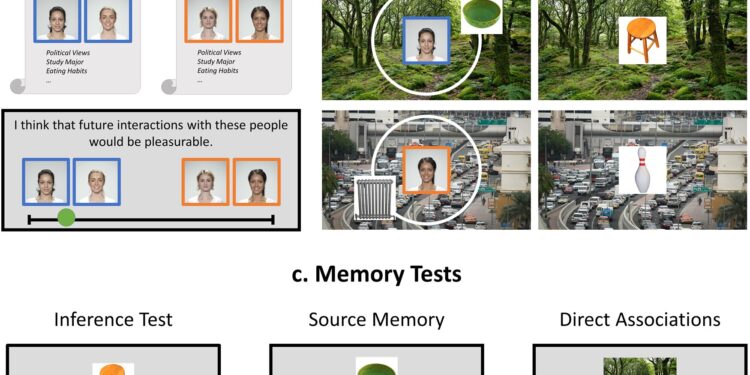

Overview of the experimental paradigm. a First, a social group manipulation was performed, in which participants chose a face for each character and assigned attributes from different categories to each team. b The coding phase was divided into two distinct coding blocks, presenting overlapping AB and BC associations, respectively. c In subsequent memory tests, participants were asked to make an associative inference by relating objects presented in the same context. Credit: Communication psychology (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s44271-023-00043-8

Our brains are “programmed” to learn more from people we like – and less from those we don’t like. This was demonstrated by cognitive neuroscience researchers in a series of experiments. Their findings are published in Communication psychology.

Memory serves a vital function, allowing us to learn new experiences and update existing knowledge. We learn from both individual experiences and their connection to draw new conclusions about the world. This way we can make inferences about things that we don’t necessarily have direct experience with. This is called memory integration and makes learning fast and flexible.

Inês Bramão, associate professor of psychology at Lund University, gives an example of memory integration: Let’s say you’re walking in a park. You see a man with a dog. A few hours later, you see the dog in town with a woman. Your brain quickly makes the connection between man and woman, even if you’ve never seen them together.

“Making such inferences is adaptive and useful. But of course there is a risk that our brains draw incorrect conclusions or remember selectively,” explains Inês Bramão.

To examine what affects our ability to learn and make inferences, Inês Bramão, along with colleagues Marius Boeltzig and Mikael Johansson, set up experiments in which participants had to remember and relate different objects. It could be a bowl, ball, spoon, scissors or other everyday objects.

It turned out that memory integration, that is, the ability to remember and relate information across learning events, was influenced by who presented it. If it was a person the participant liked, it was easier to connect the information than when the information came from a person the participant did not like. Participants provided individual definitions of “like” and “dislike” based on aspects such as political views, main orientations, eating habits, favorite sports, hobbies and the music.

The results can be applied in real life, according to the researchers. Inês Bramão takes a hypothetical example from politics: “A political party argues in favor of increasing taxes to benefit health care. Later, you visit a health care center and see that improvements have been made. If you sympathize with the party that wanted to improve health care through higher taxes, you are likely to attribute the improvements to higher taxes, even though those improvements may have a completely different cause. »

There is already plenty of research describing that people learn information differently depending on the source and how this characterizes knowledge polarization and resistance.

“Our research shows how these important phenomena can partly be attributed to the fundamental principles that govern how our memory works,” explains Mikael Johansson, professor of psychology at Lund University.

“We are more likely to make new connections and update our knowledge from information presented by groups we favor. These favored groups typically provide information that aligns with our pre-existing beliefs and ideas, potentially reinforcing points of view. polarized view.”

Understanding the roots of polarization, resistance to new knowledge, and associated phenomena related to basic brain functions offers deeper insight into these complex behaviors, researchers say. So it’s not just filter bubbles on social media but also an innate way of assimilating information.

“What is particularly striking is that we integrate information differently depending on who says something, even when the information is completely neutral. In real life, where information often triggers stronger reactions, these effects could be even more marked,” Johansson explains.

More information:

Marius Boeltzig et al, Ingroup sources improve associative inference, Communication psychology (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s44271-023-00043-8

Provided by Lund University

Quote: Study reveals our brains are “programmed” to learn more about the people we love (February 15, 2024) retrieved February 15, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.