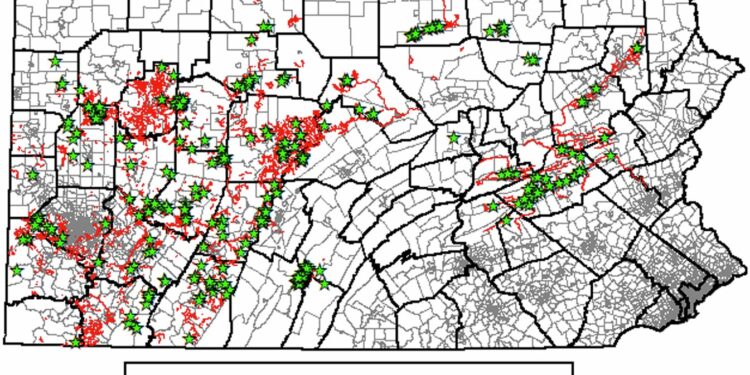

Abandoned mine drainage disrupted waterways using Datashed systems. Source: Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection and Datashed.org. Credit: Earth & Environment Communications (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s43247-024-01669-0

New research from the University of Pittsburgh shows that state and federal funding for abandoned mine drainage in Pennsylvania is effective and cost-effective in cleaning up acidic water, particularly for the benefit of vulnerable communities affected. But the research also shows that current state funding is insufficient to address all mine drainage in the long term, while also addressing other hazards associated with abandoned mines, such as sinkholes.

“Over the past 35 years, the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection and numerous watershed management groups have built more than 300 systems, with state and federal funding, to treat mine drainage before it enters nearby waterways,” said Jeremy Weber, a professor in Pitt’s Graduate School of Public & International Affairs.

Together with Katie Jo Black of Kenyon College, Weber co-authored the research published in Earth & Environment Communications.

“Data from existing treatment systems show that they protect more than 1,500 miles of streams and rivers from degradation caused by mine drainage. These systems have proven to be relatively cost-effective, protecting streams for $5,700 per mile per year. However, there remain nearly 9,000 miles of degraded streams and rivers in the state.”

Weber, who studies the politics and economics of environmental and energy issues, noted how the transition from coal to new, greener forms of energy has generated funding for cleaning up legacy pollution, retraining displaced workers, and other economic development grants. Specifically, the Infrastructure, Investment, and Jobs Act of 2021 (IIJA) allocated $16 billion to clean up abandoned pits and mines, where drainage can “hamper local economies,” the researchers said.

“Recent U.S. legislation provides a historic budget to address the dangers of abandoned mines, such as acid drainage that can turn a stream orange, kill fish and make people sick if they ingest it,” Weber said. “It’s unclear who will benefit from this investment or what it will accomplish.”

To try to find answers, their research focused on Pennsylvania, which the co-authors say contains the most abandoned mining liabilities in the United States and is expected to receive about a third of the mining funding mandated in the 2021 IIJA.

They discovered specific communities vulnerable to deleterious effects.

“Pennsylvania communities most exposed to mine drainage have incomes 30 percent lower than unaffected communities and are twice as vulnerable to the energy transition,” Weber said.

According to the co-authors, some 2.4 million people, or about 18.5 percent of Pennsylvania’s total population, live in a community (or census tract) with a waterway impaired by abandoned mine drainage. In many cases, the impairment is significant, with 500,000 people living in a community where at least half of their waterways are impaired. The researchers found that communities most affected by mine drainage are also much less prosperous than unaffected communities, with household incomes about 30 percent lower and property values 50 percent lower.

Looking at data from 265 systems, the co-authors found that the outgoing water was of much higher quality than the incoming water, indicating that the systems on average improve the quality of mine drainage before it enters nearby streams. For example, the incoming water had an average pH of 4.3, “about the acidity of tomato juice,” they wrote, while the outgoing water had an average pH closer to 6.

They estimated that nearly 6,400 miles of streams need to be protected from abandoned mine drainage, including nearly 900 miles of existing and aging streams. While cost-effective for surface water quality now, the funding they calculated for the next 25 years means Pennsylvania will need $1.5 billion to fix what’s ahead, but will need an additional $3.9 billion to address liabilities not related to mine drainage issues like sinkholes, high walls and open mine shafts.

This means, the co-authors write, that “the funds represent less than half of the amount needed.”

More information:

Katie Jo Black et al., Treating Abandoned Mine Drainage Can Cost-Effectively Protect Waterways and Benefit Vulnerable Communities, Earth & Environment Communications (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s43247-024-01669-0

Provided by the University of Pittsburgh

Quote:Study finds treating mine drainage water is cost-effective, but much higher costs are expected (2024, September 16) retrieved September 17, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.