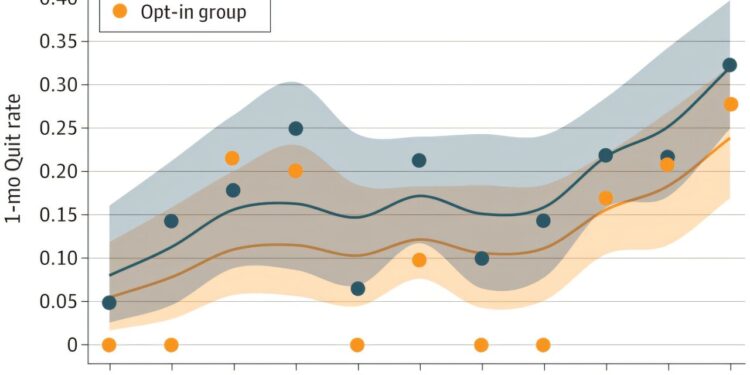

Normal dynamic linear model of the opt-out effect. Credit: Open JAMA Network (2024). DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.33802

People who smoke cigarettes and automatically receive help to quit smoking are more likely to succeed, even if they are not fully motivated at first. A new study led by researchers at the University of Kansas Cancer Center found that an opt-out approach, in which smokers are given medication and counseling to quit smoking, unless they do not refuse, significantly increases smoking cessation rates. A month after starting, 22% of people in the opt-out group had stopped smoking, compared to just 16% of the opt-in group. Their findings were recently published in Open JAMA Network.

The study was conducted among people who smoked and were patients of the University of Kansas Health System. Participants were randomly assigned to one of two groups: opt-out or opt-in treatment. In the opt-out group, unless they refused, patients automatically received all components of evidence-based tobacco treatment, including a starter kit of nicotine patches and gum, a prescription for smoking cessation medication, a treatment plan and follow-up calls.

Opt-out patients were free to refuse (“opt-out”) any component of care. In the opt-in group, patients were asked if they wanted each treatment component and received only the components they agreed to receive.

Patients were asked to choose a number between 0 and 10 to measure their desire to quit. Zero meant they were not thinking about quitting, and 10 meant they were taking steps to quit. The researchers then used Bayesian statistical methods to see how the desire to quit affected the odds of quitting, comparing opt-out and opt-in treatments.

Byron Gajewski, Ph.D., professor of biostatistics and data science and co-director of the KU Cancer Center’s Biostatistics and Informatics Shared Resource, co-authored the article with Babalola Faseru, MD, and Kimber Richter, Ph. D., both professors of population health. All three are members of the KU Cancer Center’s Cancer Prevention and Control Research Program.

The team leveraged the University of Kansas Health System’s UKanQuit program, a bedside tobacco treatment service, to conduct the study. UKanQuit has served as the basis for several major clinical trials aimed at finding the most effective methods of engaging smokers in smoking cessation programs before they are released from hospital.

“Health care providers don’t ask their patients if they would like to receive evidence-based care for other conditions like asthma, high blood pressure or diabetes,” Dr. Richter said. “They simply identify a health problem and provide the best care possible. For no reason, we have always treated tobacco addiction differently. We wanted to see what would happen if we proactively treated tobacco addiction.”

Of 739 participants, the study showed that in both groups, smokers ready to quit were more likely to quit. However, regardless of motivation level, smokers were more likely to quit if they received opt-out care than if they received opt-out care. Overall, the benefits of opt-out treatment remained the same, regardless of a person’s willingness to stop initially.

“This study is important because it shows that providing proactive help without requiring a strong initial desire to quit smoking can still make a big difference,” Dr. Gajewski said. “This suggests that opt-out treatment could be an effective strategy to help more people quit smoking.”

More information:

Byron Gajewski et al, Desire to quit smoking, refusal of anti-smoking treatment and dropout, Open JAMA Network (2024). DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.33802

Provided by the University of Kansas Cancer Center

Quote: Study finds opt-out treatment helps smokers quit, even those with low motivation (October 21, 2024) retrieved October 21, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.