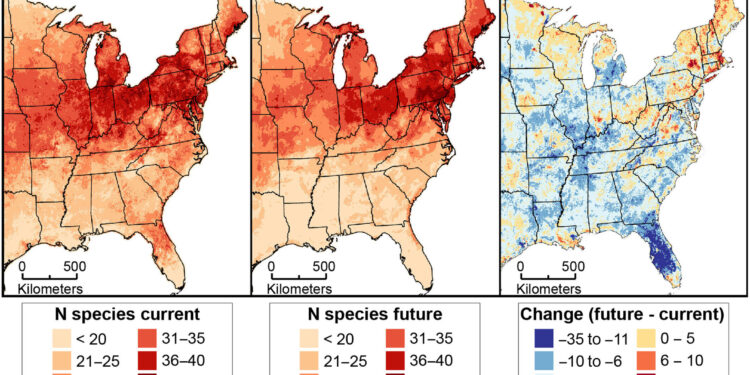

The number (N) of invasive plant species whose habitat is identified as climatically suitable for abundant populations (≥5% cover) in the eastern contiguous United States, given (a) current climatic conditions, (b) a global warming scenario of +2°C and (c) the difference between +2°C and current climate conditions. Credit: Diversity and distributions (2023). DOI: 10.1111/ddi.13787

Researchers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst recently published two papers that together provide the most detailed maps to date of how 144 common invasive plant species will respond to a 2° Celsius climate change in the east of the United States, as well as on the role of these species. that garden centers are currently playing by sowing future invasions.

Together, the articles, published in Diversity and distributions And Biosciencesand publicly available maps, which track species at the county level, promise to give invasive species managers across the United States the tools they need to proactively coordinate their management efforts and adapt now to the warmer climate of tomorrow.

Mapping Future Abundance

One of the biggest hurdles in combating the threat of invasive species is determining when and where a species crosses the line between non-native and invasive species status. A single occurrence of, for example, purple loosestrife does not constitute an invasion. Invasive plant managers need to know where a species is likely to take over, crowding out native plants and changing the ecosystem.

Or, as Bethany Bradley, professor of environmental conservation at UMass Amherst and lead author of both papers, puts it: “Managers have very few resources to control invasions, so we don’t want to waste time on our own focus on species unlikely to become invasive. in a given area. But the question of what will become invasive and where has been surprisingly difficult to answer.

“If we can proactively identify these species and the regions in which they are most likely to become abundant as the climate warms, then we can avert a major ecological threat before it is too late,” adds Annette Evans, postdoctoral fellow at UMass Amherst Northeastern University. Climate Adaptation Science Center and lead author of the paper on invasive abundance and future hotspots.

To do this, the team combed through 14 current invasive species databases compiled by hundreds of natural resource managers to first determine which species are currently abundant and where, geographically, these hotbeds are located. of abundance.

They focused on the eastern United States (east of the 100th meridian, which extends from central North Dakota to central Texas – a follow-up paper will focus on the western United States ) and found that the hottest hotspots are around the Great Lakes. , in the mid-Atlantic and along the northeastern coasts of Florida and Georgia. Each of these regions has the right combination of conditions to currently support abundant populations of more than 30 different invasive plants.

They then ran their data on 144 plants through a series of models that predicted where hot spots would occur if there was 2°C of warming.

What they found is that most species will shift their range northeast by an average of 130 miles (213 kilometers), a trend that is also reflected in shifts toward abundance hotspots. In some states, warming temperatures will make currently unsuitable areas suitable for abundant infestations of up to 21 new plant species, and range shifts could exacerbate the effects of up to 40 currently abundant invasive species . On the other hand, 62% of currently abundant invasive species will see habitat loss to large populations in the eastern United States.

But statistics are not enough. “We’ve created something even more user-friendly,” says Evans: a series of publicly available distribution maps for individual species, which can help plant managers sort out the plants that most need their attention , as well as state-specific watch lists.

How Nurseries Could Cause an Invasion

“When people think about how invasive plant species spread, they might assume that species move because of birds or wind that disperses seeds,” says Evelyn M. Beaury, lead author of the paper on horticulture and invasive species, as well as a postdoctoral researcher. at Princeton who carried out this research as an extension of his graduate studies at UMass Amherst. “But commercial nurseries that sell hundreds of different invasive plants are actually the primary pathway for invasive plant introductions.”

Although researchers have long known that invasive species are linked to the horticulture trade, Beaury and his co-authors, including Evans and Bradley, wonder how often invasive species are sold in the same area where they are abundant . And how might nurseries exacerbate the problem of climate-driven invasion?

It turns out there are a lot of answers to both of these questions.

Using a case study of 672 nurseries in the United States that sell a total of 89 species of invasive plants, then applying the results to the same models the team used to predict future hot spots, Beaury and co -authors discovered that nurseries are currently sowing invasion seeds for more than 80% of the species studied. If nothing is done, the industry could facilitate the spread of 25 species in areas that become conducive to 2°C warming.

Additionally, 55 percent of invasive species were sold within 13 miles (21 kilometers) of an observed invasion – the median distance Americans travel to purchase landscaping plants. In other words, ordinary gardeners who purchase plants from their local nurseries might unwittingly help perpetuate the invasion and associated ecological damage in their own backyards.

“But there is some good news here,” says Beaury. “This is the first time we have real numbers demonstrating the link between nursery sales and the spread of invasive species, including invasions that occur near nurseries, as well as across borders. States. Now that we have the data, we have an incredible opportunity to be proactive, working with industry, consumers and plant managers to think more critically about the impact of our gardens on ecosystems Americans.

The team also compiled a publicly available list of 24 commonly sold invasive plants at increased risk of spread via climate change in the Northeast, from butterfly bush to English ivy, to avoid, along with native alternatives, such as brush buckeye and wild blue. phlox.

“These two papers together make it very clear that not only are we facilitating current invasions through the ornamental plant trade, but we are also facilitating future climate-driven invasions,” says Bradley. “But with these documents, maps and watch lists, we can identify which species are of most concern and where, now and in the decades to come. These are important new tools in the toolbox of invasive plant managers.

More information:

Annette E. Evans et al, Shifting hotspots: Climate change projected to drive contractions and expansions of invasive plant abundance habitats, Diversity and distributions (2023). DOI: 10.1111/ddi.13787

Evelyn M Beaury et al, Horticulture could facilitate infilling and range expansion of invasive plants with climate change, Biosciences (2023). DOI: 10.1093/biosci/biad069

Provided by University of Massachusetts Amherst

Quote: Study reveals that nurseries exacerbate the spread of 80% of invasive species, due to climate (2023, December 5) extracted on December 6, 2023 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.