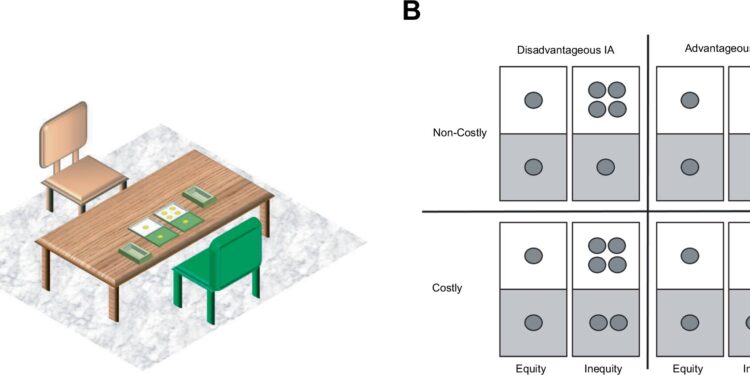

Experimental arrangement of the inequity aversion choice task. Credit: Communication psychology (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s44271-024-00139-9

How do young children perceive what is right and what is wrong, and how do they behave accordingly? Three psychologists from Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf (HHU), Tilburg University in the Netherlands and the University of Veterinary Medicine in Vienna, show in the journal Communication psychology that stereotypical gender differences exist, but that the story is actually more complicated than that.

The scenario is familiar: seven-year-old Lukas complains loudly when his friend Henry gets one more scoop of ice cream than him. Although – or even because (?) – he feels unfairly treated, he refuses to share his ice cream with his friend Léo, who doesn’t have any at all. On the other hand, Lisa shares her ice cream with Leo. The next day, however, Lukas has chocolate with him, which he happily shares with Lisa.

The first example seems to fit the stereotype: boys recognize exactly when they are at a disadvantage, but at the same time they treat other children just as unfairly. Conversely, girls are more willing to share. But this stereotype doesn’t apply to chocolate.

Three researchers, all of whom originally worked at the HHU, looked in more detail at how this sense of fairness and injustice develops in children: Professor Dr. Tobias Kalenscher, principal investigator of the psychology research team compared in Düsseldorf, Dr. Lina Oberließen, now from the Wolf Science Center at the University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna and Professor Dr. Marijn van Wingerden from the Department of Cognitive Sciences and Artificial Intelligence at Tilburg University . They describe the behavioral experiments they conducted with 332 children aged three to eight years.

Professor van Wingerden explains: “But we didn’t have ice cream or chocolate. Instead, children were paired up and had to reward each other with smiley stickers. In some cases we also added additional costs for the child handing them out, such as when handing out the stickers. stickers too. And then we observed how children behaved in different gender constellations.

Dr. Oberließen comments on the results saying: “We did indeed see gender-related effects. Girls showed more compassion than boys. It is interesting to note, however, that both sexes showed the same desire when a boy received a larger share. This suggests that boys in general were treated with greater envy.

Boys also tended to be meaner to other boys: they always selected as many stickers as possible for themselves, even if it meant their partner ended up empty-handed.

Thus, children’s fairness attitudes actually depend on gender – not only their own gender, but also the gender of the children with whom they interact.

Van Wingerden says: “We identified typical gender stereotypes: girls are more compassionate, while boys are more competitive. »

Oberließen adds: “The story is more complicated than that, however. Both sexes tend to treat boys more enviously than girls. And boys are significantly more compassionate when it comes to sharing resources with girls than with other boys.”

From the results, Professor Kalenscher concludes: “Gender stereotypes permeate today’s society. Our study highlights that gender differences in social behavior can in fact be observed empirically, even in young children, perhaps contributing to cultural gender stereotypes in adult life.

“However, we can also see that, at least in the area of fairness preferences, gender differences solidify over an extended period of time. This observation leaves room for the promotion of non-stereotypical fairness attitudes by gender during this critical period of childhood.”

More information:

Marijn van Wingerden et al, Egalitarian preferences in young children depend on the sex of the interacting partners, Communication psychology (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s44271-024-00139-9

Provided by Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf

Quote: Study finds gender influences fairness attitudes in children (October 7, 2024) retrieved October 7, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.