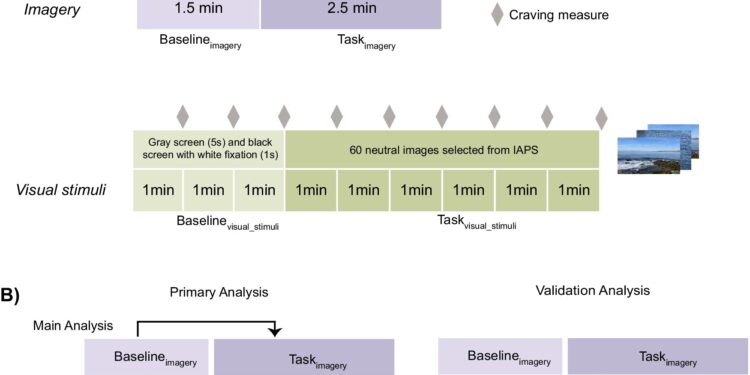

Data sets and analysis schema. Credit: Molecular psychiatry (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41380-024-02708-0

Communication between brain regions is constantly changing, but neuroimaging technologies used to analyze these interactions typically provide only a snapshot representing several minutes of changes in brain activity, obscuring instantaneous changes. Using a more dynamic approach, the Yale researchers were able to observe rapid changes in brain activity, particularly related to the experience of craving to consume.

This more nuanced view, the researchers say, provides insight into how brain activity changes over time and how it can go awry in neurological disorders.

The results were recently published in the journal Molecular psychiatry.

Previous research has shown that activity between brain regions can, among other things, predict the intensity of a person’s “craving,” or strong desire for something like food or alcohol.

“But in addition to identifying the brain regions involved in craving, I think how people engage these networks of brain regions over time also has implications,” said Jean Ye, lead author of the study and a doctoral student at the Yale School of Medicine (YSM).

“In this study, we wanted to determine whether people who experience stronger cravings engage and stay in certain brain networks more than people with less strong cravings.”

Ye works in the labs of Elizabeth Goldfarb, assistant professor of psychiatry, and Dustin Scheinost, associate professor of radiology and biomedical imaging, both of YSM and co-senior authors of the study.

For the study, 425 participants — including healthy individuals and people with alcohol use disorder, cocaine use disorder, prenatal cocaine exposure or obesity — underwent functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) while viewing either neutral images (such as landscapes) or descriptions of relaxing situations (such as sitting in a park or reading a book).

During these periods, participants were also asked to rate their level of craving for alcohol, cocaine, or food on a scale ranging from no craving at all to very strong craving.

Next, to assess brain activity specifically related to craving, the researchers combined two methods. First, they used a portion of the fMRI images — along with the participants’ craving scores — to train a machine learning model that identified brain activity networks related to craving.

The model found two networks: one in which stronger connectivity between brain regions predicted stronger craving (positive craving network) and another in which stronger connectivity predicted weaker craving (negative craving network).

The researchers then applied a technique to detect rapid changes in activity between pairs of brain regions.

“We found that people who felt a stronger need spent more time in the network state that is more positively associated with the need. They seemed to have a sticky, persistent engagement in this positive network state,” Ye said. “At the same time, they didn’t linger as much or engage as much in the negative need network state.”

Particularly important, the researchers say, may be the reduced engagement of the negative craving network, which includes brain regions involved in sensory processing and movement initiation.

Previous studies have shown that communication between these regions is associated with reduced impulsivity and cocaine use. Recruitment of the negative craving network may therefore lead to improved self-regulation and inhibition of habit-based behaviors related to substance use.

The combination of getting “stuck” in brain activity related to high craving and an inability to tap into activity related to lower craving suggests an imbalance between cognitive stability and flexibility, Ye said. And that could indicate impaired cognitive control, which is closely linked to substance use.

The other takeaway, Ye says, is that how you engage with these kinds of networks over time plays a key role in experience and behavior. And that’s likely true for other states like stress, which researchers are currently looking at, or rumination, which is dwelling on negative thoughts or feelings.

“For example, we would like to know whether people at risk for or diagnosed with depression engage more in rumination brain networks and stay there longer than people who do not have depression,” Ye said. “Those are the kinds of questions we can ask with this approach.”

More information:

Jean Ye et al, Network state dynamics underlie basal desire in a transdiagnostic population, Molecular psychiatry (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41380-024-02708-0

Provided by Yale University

Quote:’Sticky’ brain activity linked to stronger feelings of desire (2024, September 9) retrieved September 9, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.