Acoustic monitoring was carried out on soils where vegetation remains were present, as well as on degraded plots and land revegetated 15 years ago. Credit: Flinders University

Barely audible to human ears, healthy soils produce a cacophony of sound in many forms, much like an underground rave concert of popping bubbles and clicking sounds.

Special recordings made by ecologists at Flinders University in Australia show that this chaotic mix of soundscapes may be a measure of the diversity of tiny animals living in the soil, which create sounds as they move and interact with their environment.

With 75 per cent of the world’s soils degraded, the future of the vibrant community of living species that reside underground faces a bleak future without restoration, says Dr Jake Robinson, a microbial ecologist from the Frontiers of Restoration Ecology Lab in Flinders University’s College of Science and Engineering.

This new field of research aims to study the vast, teeming hidden ecosystems where nearly 60 percent of Earth’s species live, he says.

“Restoration and monitoring of soil biodiversity has never been more important. Although still in its infancy, ecoacoustics is emerging as a promising tool for detecting and monitoring soil biodiversity and is now being used in Australian bushland and other ecosystems in the UK. Acoustic complexity and diversity are significantly higher in revegetated and residual plots than in cleared plots, both in situ and in sound attenuation chambers.

“Acoustic complexity and diversity are also significantly associated with soil invertebrate abundance and richness.”

Flinders University researchers test floor acoustics (left to right) Dr Jake Robinson, Associate Professor Martin Breed, Nicole Fickling, Amy Annells and Alex Taylor. Credit: Flinders University

The latest study, involving Flinders University Associate Professor Martin Breed and Chinese Academy of Sciences Professor Xin Sun, compared acoustic monitoring results of residual vegetation to those of degraded plots and land revegetated 15 years ago. The work is published in the Journal of Applied Ecology.

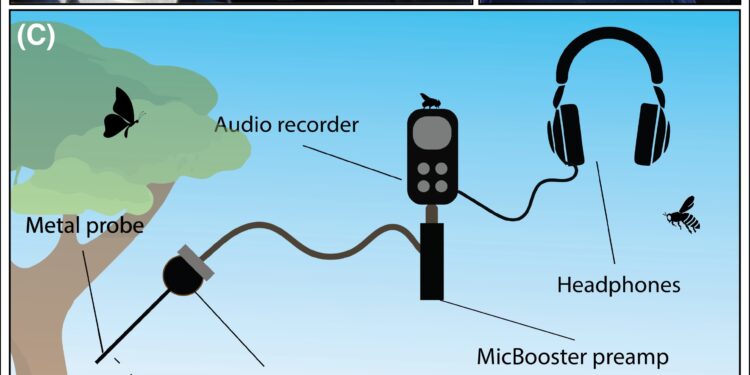

Passive acoustic monitoring used a variety of tools and indices to measure soil biodiversity over five days in the Mount Bold area of the Adelaide Hills, South Australia. A subsurface sampling device and sound attenuation chamber were used to record soil invertebrate communities, which were also counted manually.

“It is clear that the acoustic complexity and diversity of our samples is associated with the abundance of soil invertebrates – from earthworms to beetles to ants and spiders – and this appears to be a clear reflection of soil health,” says Dr Robinson. “All living organisms produce sounds, and our preliminary results suggest that different soil organisms produce different sound profiles depending on their activity, shape, appendages and size.”

“This technology holds promise for addressing the global need for more effective soil biodiversity monitoring methods to protect our planet’s most diverse ecosystems.”

More information:

Underground sounds reflect soil biodiversity dynamics across a chronosequence of grassland forest restoration, Journal of Applied Ecology (2024). DOI: 10.1111/1365-2664.14738

Provided by Flinders University

Quote:Soundscape study shows how subsurface acoustics can amplify soil health (2024, August 16) retrieved August 16, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.