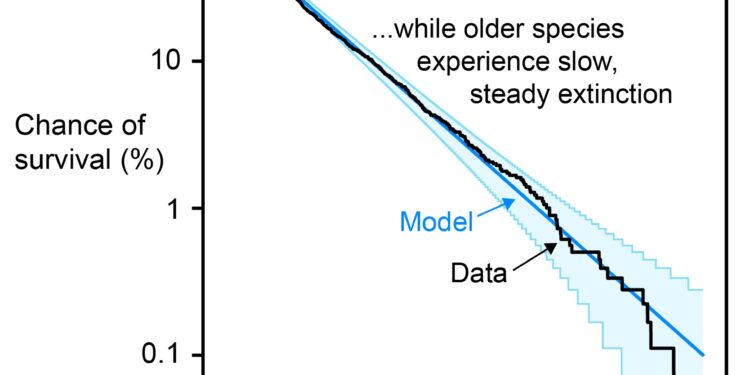

Younger species are generally at greater risk of extinction. A new model from the University of Kansas shows this new finding of age-dependent extinction while emphasizing the importance of zero-sum competition in explaining extinction, as in the old Red Queen theory. Credit: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2023). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2307629121

New research from the University of Kansas could solve a mystery in the “aging process” of species, or how a species’ risk of extinction changes after it appears on the scene.

For years, evolutionary biologists believed that older species had no real advantage over younger ones in avoiding extinction – an idea known as the “Red Queen theory” among researchers.

“The Red Queen theory is that species must keep running just to stay still, like the character in Lewis Carroll’s book ‘Through the Looking Glass,'” said lead author James Saulsbury, a postdoctoral researcher. at the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Ottawa. KU. “This idea was transformed into a kind of ecological theory in the 1970s to try to explain an observation that extinction risk did not appear to change over the lifespan of species.”

However, the years have not been kind to this theory.

“In early investigations of this phenomenon, species of all ages appeared to be disappearing at about the same rate, perhaps simply due to the relative crudeness of the evidence available at the time,” Saulsbury said. “It made sense within the framework of this Red Queen model, where species are constantly competing with other species that are also adapting alongside them.”

But as more and more data was collected and analyzed in more sophisticated ways, scientists found more and more refutations of the Red Queen theory.

“Scientists continue to discover cases where young species are particularly at risk of extinction,” Saulsbury said. “So we had a theoretical void: a bunch of anomalous observations and no unified way to understand them.”

But now Saulsbury has led research published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences this could solve this mystery. Saulsbury and his co-authors showed that the relationship between a species’ age and its risk of extinction could be accurately predicted by an ecological model called “neutral theory of biodiversity.”

Neutral theory is a simple model of ecologically similar species competing for limited resources, where the outcome for each species is more or less random.

According to this theory, “species go extinct or expand from a small initial population size to become less vulnerable to extinction, but they are still susceptible to being replaced by their competitors,” according to a simple summary of the study. PNAS paper. By extending this theory to make predictions about the fossil record, Saulsbury and colleagues found that the neutral theory “predicts the survival of fossil zooplankton with surprising accuracy and accounts for empirical deviations from Red Queen predictions more accurately.” general”.

Saulsbury’s co-authors were C. Tomomi Parins-Fukuchi of the University of Toronto, Connor Wilson of the University of Oxford and the University of Arizona, and Trond Reitan and Lee Hsiang Liow of the University of Oslo.

Although the neutral theory may seem to put an end to the Red Queen theory, the KU researcher said the Red Queen still has value. It primarily proposes the still-valid idea that species compete against each other in a zero-sum game for limited resources, always fighting for a larger piece of nature’s pie.

“The Red Queen theory has been a compelling and important idea in the evolutionary biological community, but data from the fossil record no longer appear to support this theory,” Saulsbury said. “But I don’t think our paper really disproves that idea because, in fact, the Red Queen theory and the neutral theory are, at depth, quite similar. They both present a picture of extinction occurring as a result competition between species for resources and constant renewal in communities resulting from biological interactions.

Ultimately, the findings not only help make sense of the forces that shape the natural world, but could also be relevant to conservation efforts, as species face increasing threats from climate change and loss of habitat worldwide.

“What makes a species vulnerable to extinction?” asked Saulsbury. “People are interested in knowing from the fossil record whether it can tell us anything to help conserve species. The pessimistic side of our study is that there are ecological situations in which there is not much predictability about to the fate of species; there is There is a certain limit to how much we can predict extinction. To some extent, extinction will be decided by seemingly random forces – accidents of history. There is some support for this in paleobiological studies.

He said there have been efforts to understand extinction predictors in the fossil record, but few generalities have emerged so far.

“No trait makes you immortal or impervious to extinction,” Saulsbury said. “But the optimistic side of our study is that entire communities can experience completely predictable and understandable patterns of extinction. We can get a pretty good understanding of the characteristics of the biota, such as how species risk extinction. “changes with age. Although the fate of a single species may be difficult to predict, that of an entire community can be completely understandable.”

Saulsbury added a caveat: It remains to be seen how successful the neutral explanation of extinction is in different parts of the tree of life.

“Our study also works on the geological time scale in millions of years,” he said. “Things can look very different on the scale of our own lives.”

More information:

James G. Saulsbury et al, Age-dependent extinction and the neutral theory of biodiversity, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2023). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2307629121

Provided by the University of Kansas

Quote: Scientists may have unraveled the “aging process” of species (February 20, 2024) retrieved February 20, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.