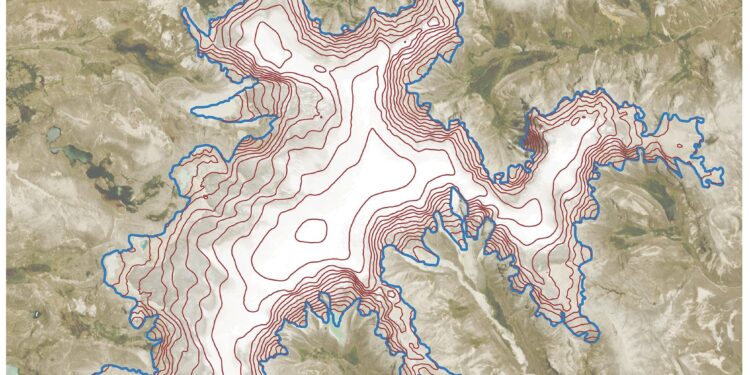

Aerial view of the Quelccaya ice cap (QIC; 13°56′ S, 70°50′ W) from October 11, 2023. The summit of the QIC reaches 5,670 m above sea level (asl) and is characterized by several outlet glaciers towards the west and a deep eastern part. Credit: The cryosphere (2024). DOI: 10.5194/tc-18-4633-2024

Natural climate events such as El Niño are causing ice loss from tropical glaciers at an alarming rate, according to a new study.

A phenomenon that typically occurs every two to seven years, El Niño causes much warmer than average ocean temperatures in the eastern Pacific, significantly affecting weather patterns around the world.

The Quelccaya Ice Sheet (QIC), in the Peruvian Andes, has been shown to be sensitive to these climate changes, but the extent to which El Niño contributes to its continued shrinkage is unclear until now.

Now, using images captured by NASA’s Landsat satellites over the past four decades, researchers have confirmed that regional warming caused periodically by El Niño has indeed led to a drastic reduction in snow-covered area. The study, led by Kara Lamantia, a graduate student at the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center at Ohio State University, found that between 1985 and 2022, the QIC lost about 58% of its snow cover and about 37% of its total surface area. .

“Our research gives us insight into the health of a glacier,” Lamantia said. “The Quelccaya glacier becomes strongly unbalanced during these short-term climate anomalies.”

The study, published in the journal The cryosphereis the first to automate the process of detecting snowy areas on the QIC. Normally, this detection is only possible through extensive field measurements or manual plotting of satellite images clear enough to detail the visual boundary between snow and ice.

Yet an algorithm developed by this team processes images using near-infrared imaging, a method that uses wavelengths outside of our visible spectrum.

“By creating a threshold for the different reflectance between snow and ice cover, we can obtain a consistent and much more reliable measurement,” Lamantia said.

Glaciers and ice caps gain mass by accumulating ice and snow and lose it when we don’t receive any, or we lose more ice than we gain. By measuring the ratio of snow-covered area to total area, researchers can quantify whether the QIC is gaining mass, losing mass, or maintaining a steady state.

The study found that during El Niño, the ratio drops significantly compared to average, indicating a drastic reduction in snow-covered area.

This extreme change in this ratio can be attributed to the large differences between dry and wet seasons in southern Peru, Lamantia said.

“All snowfall occurs during the rainy season, but during an El Niño event, southern Peru experiences warmer and drier conditions than average, so it remains dry throughout the rainy season,” a- she explained. “This means that snow cover will continue to decrease and there may be significantly less snowfall to replace it.”

As climate change rapidly alters Earth’s environment, El Niño events are expected to be longer and stronger, accelerating ice melt. This raises the possibility that QIC snow cover may not recover during La Niñas, or periods when oceans are expected to be cool.

“The ice sheet as a whole is in a very steady linear decline because of anthropogenic warming,” Lamantia said. “No matter how severe future La Niñas are; as freezing temperatures continue to rise and snow cover decreases, Quelccaya will likely continue to decline.”

If this continues, some projections suggest that the QIC’s snow cover could disappear by 2080, relegating it to a fading ice field, much like Kilimanjaro. By the end of the century, the study notes, the ice sheet could no longer exist.

It is difficult to discern how other short-term weather events might impact glacier vulnerability, something similar studies may aim to model in the future. What scientists do know is that melting ice endangers the high mountain communities that depend on it, because melting snow can quickly diminish key water supplies.

The damage already done to the oceans and atmosphere is not something we can reverse tomorrow, Lamantia said. Using the data collected on their complex interactions, researchers could have a better chance of monitoring and mitigating the planet’s climate woes.

“The general consensus is that we can expect the likely increase in the intensity and duration of El Niño to cause more complications for the QIC,” Lamantia said. “We need to start being smart about how we use and conserve our water resources.”

More information:

Kara A. Lamantia et al, El Niño increases snowline rise and ice loss on the Quelccaya Ice Sheet, Peru, The cryosphere (2024). DOI: 10.5194/tc-18-4633-2024

Provided by Ohio State University

Quote: Researchers associate El Niño with accelerated melting of ice in the tropics (October 8, 2024) retrieved October 8, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.