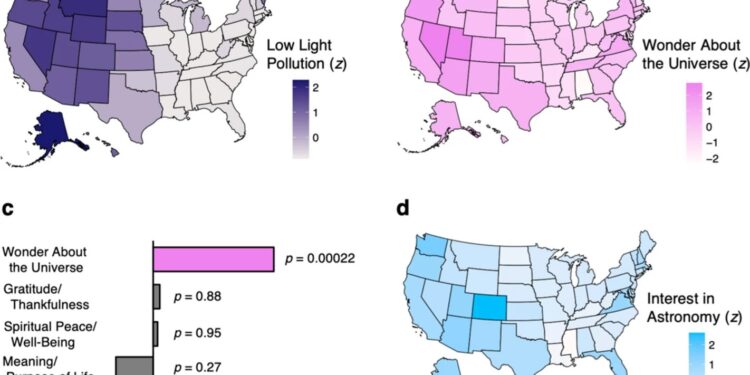

State maps of low light pollution, questions about the universe, interest in astronomy and correlations between measurements. Credit: Scientific reports (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-024-69920-4

Imagine yourself walking outside on a dark, cloudless evening. You look up to admire the stars, maybe even a planet, if you’re lucky, and a sense of wonder washes over you. New research from the University of Washington shows it could be more than a memorable experience: It could ultimately spark scientific curiosity and influence life choices.

Rodolfo Cortes Barragan, a researcher at the UW Institute for Learning and Brain Sciences (I-LABS), and Andrew Meltzoff, co-director of I-LABS and professor of psychology, recently co-authored a study in Scientific reports showing a link between the ability to see the stars without being blocked by light pollution and an interest in astronomy.

UW News spoke with the authors about their study and its surprising implications for expanding access to science and education.

Where did the idea for this study come from?

Barragan: As psychologists, we know that environmental changes can impact people’s behavior. Yet the changes caused by light pollution – a hot topic in astronomy, biology and environmental sciences – have received little attention from the social sciences.

We found it important to examine how light pollution might affect the human mind, focusing on the consequences of light pollution on human emotions and scientific behavior.

Meltzoff: Astronomy often functions as a “gateway” to science as a whole. People, including young children, look up and are enchanted by the sight of the starry sky. They feel a sense of wonder that triggers curiosity about themselves and the universe.

Many famous astronomers have noted that they got their start in science based on childhood experiences wondering about the night sky. We decided to study these reports scientifically.

How do you define the feeling of wonder at the universe?

Barragan: The feeling of “wonder” is a particular conjunction of emotions. It implies awe and astonishment. It involves curiosity, the desire to know more. It’s joyful. It implies exaltation.

To examine wonder, we used a nationally representative survey of more than 35,000 U.S. residents conducted by the Pew Research Center. This survey included a question about “people’s wonder about the universe.” We combined these results with previously reported detailed physical measurements of light pollution.

We found that U.S. populations who live with low light pollution report feeling more “amazed by the universe.” It was a specific relationship. Light pollution was not related to other emotions assessed in the same Pew survey, but it was strongly related to wonder.

Just as importantly, we found that “wonder about the universe” was directly linked to people’s behavioral interest in astronomy. We used a wide range of measures of interest in astronomy, including behaviors such as using Google to search for “astronomy,” signing up to have one’s name sent to Mars aboard the Perseverance rover, and even applying to become a NASA astronaut.

In other words, the data showed us that in areas of the United States where light pollution is low, feelings of wonder about the universe and interest in astronomy are high . Characteristics of the physical environment are related to people’s psychological experience as well as their actual behavior.

Can you expand on the idea raised in the paper that light pollution is an equity issue?

Barragan: We all want all children and adults to have the same opportunities for inspiration and science. But what our results suggest is that Americans, depending on where they live, don’t have equitable access to the night sky, which often drives interest in science. If you can’t experience something, it’s not as easy to be motivated by it.

Meltzoff: If a child grows up in an environment where they don’t see the stars, they are less likely to ask childish questions about them: “Why do the stars twinkle?” or “How many are there up there?” It is a powerful experience for a child to be able to see the Milky Way and the Big Dipper, but many children no longer have this opportunity.

Seeing the starry sky can change children’s behavior in a good way. For example, if a child can see the stars, they might learn about astronomy or space exploration and start to dream. Astronomy can indeed be an “entry” science that attracts children, both boys and girls, to curiosity-driven programs and social clubs.

What overall image do you want to convey about this study?

Barragan: We hope that our study will inspire more research in this direction and that this work combining psychology and astronomy will trigger the “I wonder” reflex in other scientists, thereby incentivizing interdisciplinary work across the arts and sciences.

Meltzoff: This study brings together two wonders that have inspired scientists and poets throughout the ages: the heavens above and our human actions on earth. One is studied by astronomers and the other by psychologists. Can we connect the two? A childish question indeed, but one that motivates us to try to dig deeper and find out more.

More information:

Rodolfo Cortes Barragan et al, The ability to see the starry sky is linked to human emotion and behavioral interest in astronomy, Scientific reports (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-024-69920-4

Provided by the University of Washington

Quote: Q&A: Researchers examine link between light pollution and interest in astronomy (October 2, 2024) retrieved October 2, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.