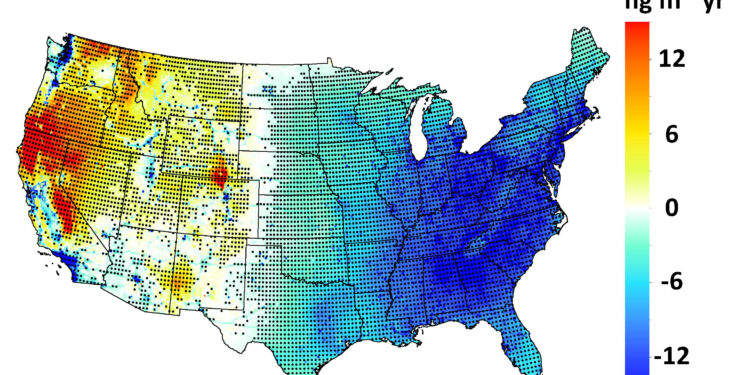

Researchers at the University of Iowa have found that wildfires originating in the western United States and Canada have erased air quality gains over the past two decades and caused an increase in premature deaths in fire-prone areas and downwind regions. This map shows areas with the highest concentrations (in red) of black carbon, a fine-particle air pollutant associated with human respiratory and heart disease. Credit: Jun Wang Lab, University of Iowa

We only need to remember last summer’s wildfires in the United States and Canada, which polluted the air from coast to coast, to know the effects these fires can have on the environment and human health.

A new study has taken stock of two decades of wildfires on air quality and human health in the continental United States. The authors report that from 2000 to 2020, air quality deteriorated in the western United States, primarily due to increased frequency and ferocity of wildfires. Wildfires caused an increase of 670 premature deaths per year in the region during this period.

Overall, the study authors report that the fires undermined successful federal efforts to improve air quality, primarily through reducing automobile emissions.

The study, “Trends in Long-Term Mortality Burden Attributed to Black Carbon and PM2.5 from Wildfire Emissions in the Continental United States from 2000 to 2020: A Deep Learning Modeling Study” , is published online on December 4 in the journal. Lancet Planetary Health.

“Our air is supposed to be getting cleaner due mainly to EPA emissions regulations, but the fires have limited or erased these air quality gains,” says Jun Wang, Professor James E Ashton and director of the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry. Engineering, deputy director of the Iowa Technology Institute at the University of Iowa and senior corresponding author of the study.

“In other words, all of the EPA’s efforts over the past 20 years to make our air cleaner have been in vain in fire-prone areas and downwind regions. We are losing ground.”

The researchers calculated the concentration of black carbon, a fine-particle air pollutant associated with respiratory and heart disease, on a kilometer-by-kilometer (0.6 mile) grid for the continental United States.

In the western United States, researchers report that black carbon concentrations have increased by 55% on an annual basis, primarily due to wildfires.

Not surprisingly, the highest premature mortality rates were in the western United States, the region where the wildfires originated or was most affected by smoke from Canadian wildfires . The authors say the increase of 670 premature deaths per year is a conservative estimate, because the effects of black carbon on human health are not fully understood.

“Wildfires have become increasingly intense and frequent in the western United States, leading to a significant increase in smoke-related emissions in populated areas,” Wang and his team write. “This likely contributed to a decline in air quality and an increase in attributable mortality.”

The fires also affected the Midwest. Smoke carried in the atmosphere affects air quality, even if the direct effects on health seem, for the moment, minimal. But, says Wang, “we are at the limit. If fires increase or become more frequent, our air quality will deteriorate.”

The eastern United States did not experience any major declines in air quality during the 2000-2020 period.

The researchers derived black carbon concentrations and premature death estimates from satellite data and 500 ground stations that monitor air quality. Data from surface stations may be plentiful, but they do not provide complete spatial coverage and may be lacking in rural areas.

Thus, the researchers used “deep learning”, which allows computer systems to group data and produce precise forecasts, to calculate black carbon concentrations. They calculated premature deaths using a formula incorporating average lifespan, exposure to black carbon and population density.

“This is the first time we have looked at black carbon concentrations everywhere, and at a resolution of one kilometer,” Wang says.

Jing Wei, the lead author of the study, led the collection of satellite data on fine particles and the public health analysis of these pollutants when he was a postdoctoral researcher in Wang’s research group in the Iowa.

“The growing number and intensity of wildfires in the United States are thwarting, if not eclipsing, reductions in anthropogenic emissions, exacerbating air pollution and increasing risks of morbidity and mortality,” says Wei, today now an assistant research scientist at Earth System Science at the University of Maryland. Interdisciplinary center.

More information:

Jing Wei et al, Long-term mortality burden trends attributed to black carbon and PM2.5 from wildfire emissions across the continental United States from 2000 to 2020: a modeling study deep learning, Lancet Planetary Health (2023).

Provided by University of Iowa

Quote: Research shows wildfires erased two decades of air quality gains in western U.S. (December 4, 2023) retrieved December 5, 2023 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.