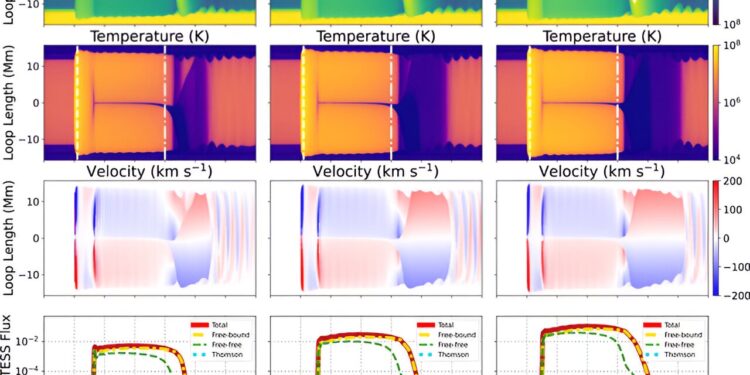

Modeled rocket atmosphere and synthesized TESS light curves. Credit: The Astrophysics Journal (2023). DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/ad077d

Our sun actively produces solar flares that can impact Earth, with the strongest flares potentially causing power outages and disrupting communications, potentially on a global scale. Although solar flares can be powerful, they are insignificant compared to the thousands of “super flares” observed by NASA’s Kepler and TESS missions. “Super flares” are produced by stars 100 to 10,000 times brighter than those of the Sun.

The physics are thought to be the same between solar flares and super flares: a sudden release of magnetic energy. Superflabby stars have stronger magnetic fields and therefore brighter flares, but some exhibit unusual behavior: a short-lived initial brightness enhancement, followed by a longer-lived but less intense secondary flare.

A team led by Kai Yang, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Hawaii Institute of Astronomy, and Associate Professor Xudong Sun developed a model to explain this phenomenon, which was published today in The Astrophysics Journal.

“By applying what we learned about the sun to other, cooler stars, we were able to identify the physics behind these flares, even though we were never able to see them directly,” Yang said. “The changing brightness of these stars over time actually helped us ‘see’ these flares that are really much too small to observe directly.”

Light curves

The visible light from these flares was thought to come only from the lower layers of a star’s atmosphere. Particles powered by magnetic reconnection fall from the hot, tenuous corona (outer layer of a star) and heat these layers.

Recent work has hypothesized that emission from coronal loops (hot plasma trapped by the solar magnetic field) might also be detectable for superflare stars, but the density in these loops is expected to be extremely high. Unfortunately, astronomers had no way to test this, because there is no way to see these loops on stars other than our own sun.

Other astronomers, using data from the Kepler and TESS telescopes, have spotted stars with a particular light curve, similar to a celestial “peak hump,” a jump in brightness. It turns out that this light curve resembles a solar phenomenon in which a second, more gradual peak follows the initial burst.

“These light curves reminded us of a phenomenon we observed on the Sun called late-phase solar flares,” Sun said.

Produce similar late phase brightness

The researchers asked: “Could the same process – large, energized stellar loops – produce similar late-phase brightness enhancements in visible light?

Yang addressed this question by adapting fluid simulations frequently used to simulate solar flare loops and increasing the loop length and magnetic energy. He found that the large input of energy from the flare injects significant mass into the loops, resulting in dense, bright visible light emission, as expected.

These studies revealed that we only see such bright light when the very hot gas cools in the uppermost part of the loop. Due to gravity, this luminous material then falls, creating what we call “coronal rain,” which we often see on the sun. This gives the team confidence that the model should be realistic.

More information:

Kai E. 凯 Yang 杨 et al, A possible mechanism for the “late phase” of stellar white light flares, The Astrophysics Journal (2023). DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/ad077d

Provided by University of Hawaii at Manoa

Quote: Discovery of the physics behind the unusual behavior of stellar superflares (December 6, 2023) retrieved on December 7, 2023 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.