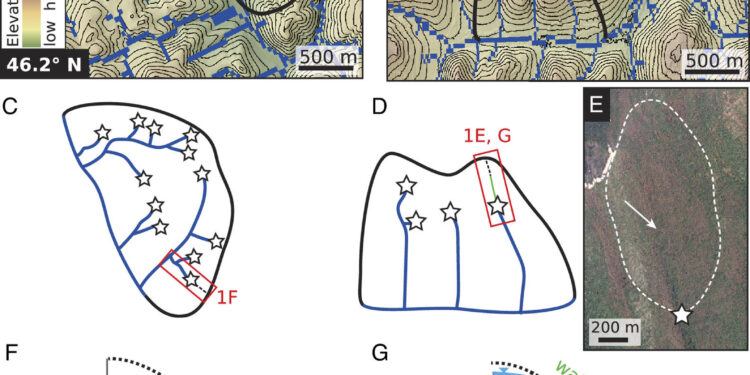

Comparison between drainage densities and hydrogeomorphic configurations in permafrost and temperate landscapes with comparable relief and annual precipitation. Credit: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2024). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2307072120

New research from Dartmouth College provides the first evidence that frozen Arctic soil is the dominant force shaping Earth’s northernmost rivers. Permafrost, the thick layer of soil that remains frozen for two years or more, is why Arctic rivers are uniformly confined to smaller areas and shallower valleys than southern rivers, according to a study carried out in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

But permafrost also constitutes an increasingly fragile reservoir containing large quantities of carbon. As climate change weakens Arctic permafrost, researchers calculate that every 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit (1 degree Celsius) of global warming could release as much carbon as 35 million cars emit in a year, as waterways Polar poles expand and stir up the thawing ground.

“The entire surface of the Earth is in a tug-of-war between processes like hill slopes that smooth the landscape and forces like rivers that cut them,” said first author Joanmarie Del Vecchio, who led the study. study as a Neukom Postdoctoral Fellow at Dartmouth with her advisors and study co-authors Marisa Palucis, assistant professor of earth sciences and Colin Meyer professor of engineering.

“We understand physics at a fundamental level, but when things start to freeze and thaw, it’s hard to predict which team is going to win,” Del Vecchio said. “If the slopes gain, they’re going to bury all the carbon trapped in the ground. But if things get warmer and the river channels suddenly start to gain, we’re going to see a lot of carbon being released into the atmosphere. likely creating this feedback loop of warming that leads to the release of more greenhouse gases.

Researchers sought to understand why Arctic watersheds – the total drainage area of a river and its connected waterways – tend to have less river area than watersheds in warmer climates, which may have vast tributaries that spread across the landscape. Del Vecchio, now a visiting scholar at Dartmouth and an assistant professor at the College of William and Mary, conceived the study in 2019 while conducting field work in Alaska. She climbed up from her riverside yard and looked out over a view of steep mountain slopes, with no rivers or streams.

“It seemed like the slopes were winning and the chains were losing,” Del Vecchio said. “We wanted to test whether temperature shapes this landscape. We are very fortunate to have such a large amount of digital surface and elevation data produced over the last few years. We could not have done this study ago a few years. “.

Researchers examined the depth, topography and soil conditions of more than 69,000 watersheds across the Northern Hemisphere, from just above the Tropic of Cancer to the North Pole, using satellite data and climate. They measured the percentage of land occupied by each river’s canal network in its watershed, as well as the slope of the river valleys.

Forty-seven percent of the watersheds analyzed are shaped by permafrost. Compared to temperate watersheds, their river valleys are deeper and steeper, and about 20% less of the surrounding landscape is occupied by canals. These similarities remain despite differences in glacial history, background topographic slope, annual precipitation and other factors that would otherwise govern the push and pull of water and land, the researchers report. Arctic watersheds are shaped by the one thing they have in common: permafrost.

Dartmouth researchers sought to understand why watersheds in the Arctic tend to have less river area than watersheds in warmer climates. The first author, Joanmarie Del Vecchio (pictured), conceived the study while doing fieldwork in Alaska after climbing from her riverside worksite and gazing at views of steep mountain slopes, no interrupted by rivers or streams. Credit: Mulu Fratkin

“No matter how we slice it, regions with larger and more abundant river channels are warmer with a higher average temperature and less permafrost,” Del Vecchio said. “It takes a lot more water to carve out valleys in permafrost areas.”

Permafrost’s power to limit the footprint of Arctic rivers also allows it to store large amounts of carbon in the frozen earth, the study found. To estimate the carbon that would be released from these watersheds due to climate change, the researchers combined the amount of carbon stored in permafrost with the soil erosion that would result from thawing of the ground and be carried away by spreading Arctic rivers. .

Research suggests the Arctic has warmed more than 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit (2 degrees Celsius) above pre-industrial levels, or about since 1850, Del Vecchio said. Scientists estimate that a gradual thawing of Arctic permafrost could release between 22 and 432 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide by 2100 if current greenhouse gas emissions are brought under control – and up to 550 billion tonnes in otherwise, she said. The International Energy Agency estimates that energy consumption in 2022 released more than 36 billion tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, an unprecedented record.

The Arctic has been adapted to the cold for so long that scientists have no idea how much or how quickly carbon will be released if permafrost melted more quickly, said Palucis, whose research group uses the Arctic as a substitute. for Mars to study the surface processes of the red planet. “Even though the Arctic has experienced warming in the past, what’s frightening is how quickly it’s happening today. The landscape has to respond quickly and that can be traumatic,” she said. declared.

Palucis remembers a research trip to the Arctic when she saw a piece of bedrock the size of a small building break away from a cliff. The culprit of the bursting was a small trickle of water which had seeped into the rock and weakened it.

“This is a landscape adapted to colder conditions, so when you change it, even a small amount of water flowing through the rock is enough to cause a substantial change,” Palucis said.

“Our understanding of Arctic landscapes is more or less the same as we had with temperate landscapes 100 years ago,” she said. “This study is an important first step in showing that the models and theories we have for temperate watersheds simply cannot be applied to polar regions. It’s a whole new set of doors to walk through to understanding these landscapes .”

Sediment cores collected in the Arctic showed significant soil runoff and carbon deposition about 10,000 years ago, suggesting a much warmer region than exists now, Del Vecchio said. Today, areas like Pennsylvania and the mid-Atlantic United States, located just south of the farthest reaches of Ice Age glaciers, portend the future of the modern Arctic.

“We have evidence from the past that a lot of sediment was released into the ocean during warming,” Del Vecchio said. “And now we have a snapshot from our paper showing that the Arctic will receive more water channels as it warms. But none of this amounts to saying, ‘This is what happens when you take a cold landscape and you actually increase the temperature ‘rapidly.’ I don’t think we know how that’s going to change.”

More information:

Joanmarie Del Vecchio et al, Permafrost extent defines drainage density in the Arctic, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2024). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2307072120

Provided by Dartmouth College

Quote: Permafrost alone holds back Arctic rivers – and a large amount of carbon (February 1, 2024) recovered on February 1, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.