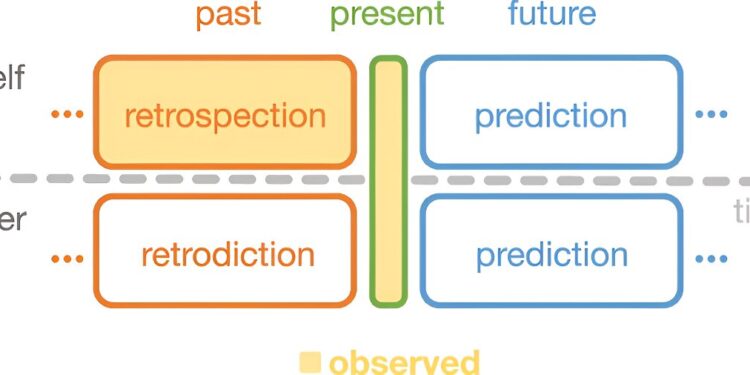

Retrospection, retrospection and prediction. Credit: Natural communications (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-52627-5

If you started watching a movie from the middle without knowing its plot, you’d probably be better at inferring what happened earlier than predicting what’s going to happen next, according to a new Dartmouth-led study published In Natural communications.

Previous research has shown that humans are generally equally good at guessing the unknown past and future. However, these studies relied on very simple sequences of numbers, images or shapes, rather than more realistic scenarios.

“Real-life events have complex time-related associations that have not typically been captured in previous work. So we wanted to explore how people make inferences in situations more reminiscent of everyday life.” , says lead author Jeremy Manning, associate. professor of psychological and brain sciences at Dartmouth and director of the Contextual Dynamics Lab at Dartmouth. “Real-life experiences, unlike abstract sequences, often include other people.”

For the study, participants watched a series of scenes from two character-driven television series, “Why Women Kill” on CBS and “The Chair” on Netflix. They were asked to either guess what happened before each scene or what would happen next.

Participants were consistently better at guessing what had happened before a scene they had just watched than at guessing what would happen next.

The researchers found that participants’ inferences were strongly influenced by references to specific past and future events in the characters’ conversations. Like people in real life, the characters in both series often talked about their past experiences and future plans. Because the characters in these two series tended to talk more about their pasts, participants had more clues to draw on to draw conclusions about past events rather than future events.

To determine whether this trend of talking more about the past extends to other conversations as well, the team analyzed millions of dialogues in novels, films, TV shows, and more. They found that both fictional and real people tend to talk more about their past than their future.

Although we can make plans for the future, our memories only tell us about our past. Just as real people remember their past experiences but not those of the future, fictional characters do so too, perhaps in the writers’ attempt to help them appear realistic, according to the co-authors.

“Our results show that on average, people talk about the past one and a half times more than the future,” says Manning. “And that seems to be a general trend in human conversations.”

Previous research has referred to the phenomenon of remembering the past but not the future as the “psychological arrow of time.” “This phenomenon also reflects the fact that one knows more about one’s past than one’s future,” says lead author Xinming Xu, Guarini, a Ph.D. student in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences and member of the Contextual Dynamics Laboratory.

“Our study shows that a person’s asymmetric knowledge about their own life can be transmitted to others.”

Ziyan Zhu of Peking University and Xueyao Zheng of Beijing Normal University also contributed to the study.

More information:

Xinming Xu et al, Temporal asymmetries in inferring unobserved past and future events, Natural communications (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-52627-5

Provided by Dartmouth College

Quote: People infer the past better than the future, according to a study (October 3, 2024) retrieved October 3, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.