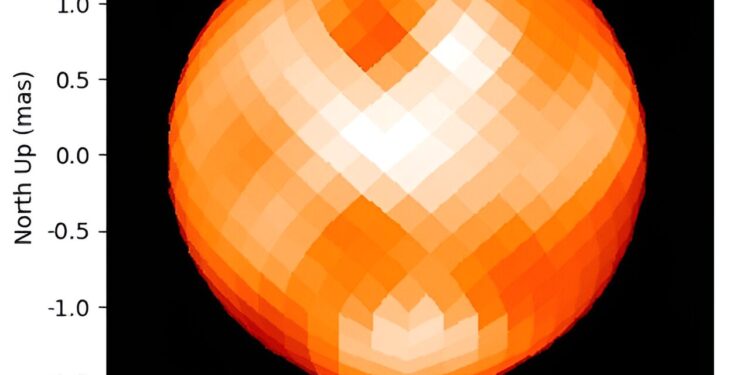

False-color image of Polaris taken in April 2021 by CHARA Array, which reveals large light and dark spots on the surface. Polaris appears about 600,000 times smaller than the full moon in the sky. Credit: Georgia State University / CHARA Array

Researchers using Georgia State University’s High Angular Resolution Astronomy Array (CHARA) have identified new details about the size and appearance of the North Star, also known as Polaris. The new research is published in The Journal of Astrophysics.

The Earth’s North Pole points to a direction in space marked by the North Star. Polaris is both a navigational aid and a notable star in its own right. It is the brightest member of a triple star system and a pulsating variable star. Polaris periodically brightens and dimmers as the star’s diameter increases and decreases over a four-day cycle.

Polaris is a type of star known as a Cepheid variable. Astronomers use these stars as “standard candles” because their true brightness depends on their pulsation period: brighter stars pulsate more slowly than fainter stars. The brightness of a star in the sky depends on its true brightness and its distance from the star. Because we know the true brightness of a Cepheid based on its pulsation period, astronomers can use them to measure distances to their host galaxies and to infer the expansion rate of the universe.

A team of astronomers led by Nancy Evans at the Harvard Center for Astrophysics and the Smithsonian observed Polaris using the CHARA optical interferometer array of six telescopes at Mount Wilson, California. The goal of the study was to map the orbit of the faint, nearby companion that orbits Polaris every 30 years.

“The small separation and large brightness contrast between the two stars make it extremely difficult to resolve the binary system during their closest approach,” Evans said.

The CHARA array is located at the Mount Wilson Observatory in the San Gabriel Mountains of Southern California. The six CHARA telescopes are arranged along three arms. Light from each telescope is carried by vacuum tubes to the central beam combiner laboratory. All beams converge on the laboratory’s MIRC-X camera. Credit: Georgia State University

The CHARA array combines light from six telescopes spread across the mountaintop of the historic Mount Wilson Observatory. By combining the light, the CHARA array acted as a 330-meter telescope to detect the faint companion as it passed close to Polaris. The Polaris observations were recorded using the MIRC-X camera built by astronomers at the University of Michigan and the University of Exeter in the United Kingdom. The MIRC-X camera has the remarkable ability to capture details of stellar surfaces.

The team successfully tracked the orbit of the nearby companion and measured the changes in size of the Cepheid as it pulsated. The orbital motion showed that Polaris has a mass five times that of the Sun. Images of Polaris showed that its diameter is 46 times larger than that of the Sun.

The biggest surprise was the appearance of Polaris in close-up images. CHARA’s observations provided the first glimpse of what the surface of a Cepheid variable looks like.

“CHARA images revealed large bright and dark spots on Polaris’ surface that have changed over time,” said Gail Schaefer, director of the CHARA network. The presence of spots and the star’s rotation could be related to a 120-day variation in the measured speed.

“We plan to continue photographing Polaris in the future,” said John Monnier, a professor of astronomy at the University of Michigan. “We hope to better understand the mechanism that generates the spots on Polaris’ surface.”

The new Polaris observations were made and recorded as part of the CHARA network’s open-access program, where astronomers around the world can request time through the National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory (NOIRLab).

More information:

Nancy Remage Evans et al., The orbit and dynamical mass of Polaris: observations with the CHARA network, The Journal of Astrophysics (2024). DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/ad5e7a

Provided by Georgia State University

Quote:New view of North Star reveals speckled surface (2024, August 20) retrieved August 20, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.