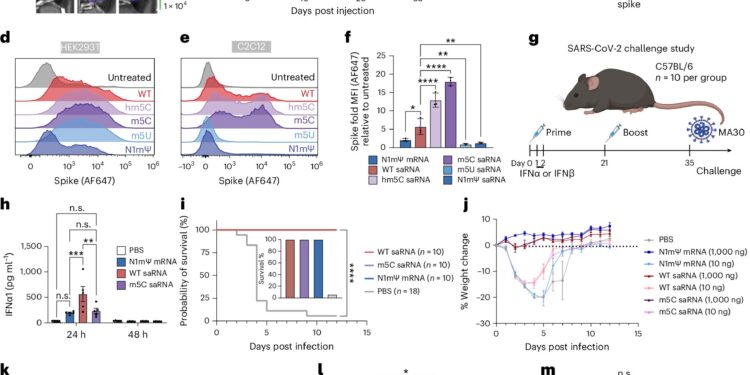

Development and characterization of a fully modified sRNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2. Credit: Biotechnology of nature (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41587-024-02306-z

It all started in a lab. Two Boston University PhD students, Joshua McGee and Jack Kirsch, were creating and testing different types of RNA, strands of ribonucleic acid made up of chains of chemicals called nucleotides that help carry genetic instructions into cells. They wanted to see if RNA sequences created with small changes to their nucleotides could still work. After running dozens of experiments, they hit a dead end.

“At first it was a failure,” McGee said.

Decades of research have uncovered the mysteries of RNA in living cells. Without it, our cells couldn’t perform fundamental tasks, like building other cells, transporting amino acids from one part of the cell to another, or triggering immune responses to viruses.

But more recently, scientists have discovered how to harness RNA to create treatments for genetic diseases and cancer. They’ve also learned how to use messenger RNA (mRNA) to make COVID-19 vaccines. McGee and Kirsch’s experiments aim to use RNA to deliver lifesaving drugs and create vaccines that are more effective than the ones we have today.

Working with Mark Grinstaff, the William Fairfield Warren Distinguished Professor of Biomedical Engineering and Chemistry at Boston University, and Wilson Wong, an associate professor of biomedical engineering in the College of Engineering, they began discussing what to do next and what to do with the remaining chemical components from the initial experiments.

They decided to focus on changing the chemical structure of a lesser-known type of RNA, called self-amplifying RNA (saRNA), which is made in the lab and replicates multiple times in a cell to produce more of the proteins it is programmed to make.

The new method worked: their modified saRNA replicated in a Petri dish.

“We responded with great enthusiasm, but we also wondered, as we always do, if we had done the right thing,” McGee says. “We did it again and again. And we got the same results.”

The results kicked off a yearlong research project that moved from Grinstaff’s chemistry lab to Wong’s genetic engineering lab and then to Boston University’s National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories (NEIDL), where they tested their modified saRNA as a vaccine against the COVID-19 virus. They found that a lower dose of their new vaccine in mice protected them from the disease as well as current mRNA vaccines. Their results are published in Biotechnology of nature.

It will take years of additional testing before this vaccine can be approved for humans. While there is a type of saRNA vaccine (approved last year in Japan), the researchers hope their modified version will make the technology more attractive to drugmakers and overcome the challenges of using saRNA as a vaccine.

“The challenge with regular self-amplifying RNA is that there are two competing processes: the RNA is trying to make more and more proteins, and at the same time the immune system is degrading them,” Grinstaff says.

Traditional mRNA COVID-19 vaccines instruct cells to produce a spike protein that mimics the real virus. This allows the immune system to kick in and fight the virus. But an saRNA vaccine goes a step further by repeating these instructions to the cell over and over again, building more machines to create the spike proteins. The more proteins, the fewer high doses needed, and the immune system remembers how to fight the virus over a longer period of time.

“So the idea is that this could give you a long duration of protein expression, even using a lower dose,” Grinstaff says.

Another challenge is that saRNA could create too strong a reaction that could lead to unpleasant side effects, worse than those of current COVID vaccines, which typically cause some people to have a mild fever or aches.

Grinstaff, Wong and their team worked closely with Florian Douam, assistant professor of virology, immunology and microbiology at Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine and a NEIDL faculty member. He and his team conducted a study, called a “viral challenge,” to assess whether a COVID-19 vaccine made using modified saRNA technology could protect mice more effectively against severe COVID-19 disease than previous saRNA and mRNA vaccines.

“The virological aspect was particularly important,” Douam says. “It showed how a very low dose of this new saRNA technology is able to protect mice from a fatal disease much more effectively than traditional saRNA and mRNA COVID-19 vaccines at a similar dose.” Douam says the new vaccine, which incorporates modified nucleotides called m5C (5-methylcytidine), also triggered very low levels of inflammation upon vaccination, comparable to mRNA vaccines.

“There is still a lot of work to be done to unveil the full advantages of this technology over other existing RNA vaccine approaches,” Douam says. But it’s a promising start.

The next question is whether their modified saRNA can provide longer-lasting protection against viral infection compared to existing RNA-based vaccines at a similar dosage.

More promising treatments

Beyond COVID vaccines, the team’s well-tolerated saRNA could open the door to other types of treatments and gene therapy.

“Ultimately, it’s a protein production system,” Wong says, “a gene delivery system.”

In the case of a genetic disease, saRNA could be programmed to produce a missing gene or replace a defective gene, Wong says. To treat lung, breast and other cancers, “we can make it produce an anticancer drug for a disease that requires a high dose and the production of a large amount of protein.”

“That’s why we’re really excited about our self-amplifying RNA technology, because we think we can reduce the dose needed to enable some of these therapeutic applications,” Wong says. “That’s how we envision it.”

“We’re working to better understand what we found,” says McGee, who was co-supervised by Wong and Grinstaff. “There’s been a lot of literature suggesting that saRNA research would fail, too. That made me realize that it’s okay to try things that other people think might fail, because who knows, they might be wrong.”

More information:

Joshua E. McGee et al., Full substitution with modified nucleotides in self-amplifying RNA suppresses interferon response and increases potency, Biotechnology of nature (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41587-024-02306-z

Provided by Boston University

Quote:New type of RNA could improve vaccines and cancer treatments (2024, September 11) retrieved September 11, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.