Older adults select different, but not simpler, strategies than younger adults when making risky choices. Credit: PLOS Computational Biology (2024). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1012204

As we move through life, the way we manage our money and make financial decisions naturally changes. Previous research has shown that when making financial decisions, older adults are sometimes more willing to take risks than younger adults. But what are the cognitive processes behind these age-related changes in risk taking?

The common explanation for changes in decision-making is that as we age, our cognitive abilities decline, making us less equipped to handle risky or complex financial decisions. But are differences in risk-taking actually driven by the limited mental resources of older people? And what do they tell us about intelligence?

A new study titled “Older adults select different but not simpler strategies than younger adults in risky choices,” led by Florian Bolenz and Thorsten Pachur of Science of Intelligence (SCIoI) in Berlin and published in PLOS Computational Biologychallenges the idea that older people necessarily rely on simpler strategies.

Research demonstrates that the decision strategies employed by older adults are just as complex as those of younger adults, even though these strategies reflect different risk propensities and motivations.

Reframing cognitive aging

Using a new computational model based on resource-efficient strategy selection, the study analyzed data from 122 participants, split between younger (18 to 30 years old) and older (63 to 88 years old) adults. , as they made decisions in 105 risky scenarios. . The resource-rational strategy selection model explains how people make decisions by balancing the benefits of a strategy with the mental effort required, and suggests that they are influenced by the value they place on the strategy. ease rather than reward.

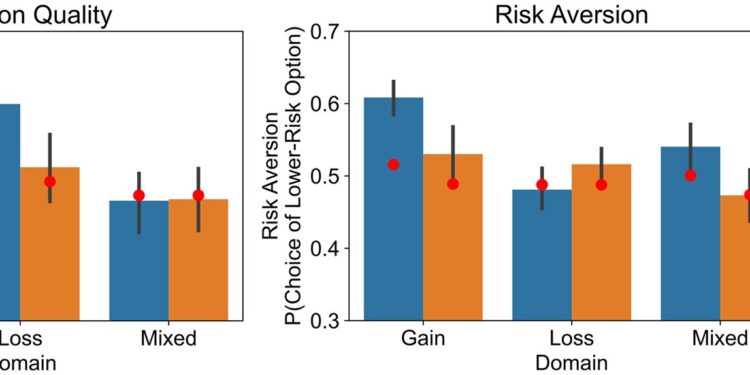

Researchers simulate decision-making models to understand the strategies people use. Contrary to some previous hypotheses, the results show that older people do not adopt simpler strategies by default. In fact, young adults often use what’s called the “minimax heuristic.” This strategy focuses on minimizing potential losses. Essentially, they play it safe and aim to avoid the worst possible outcome, even if it means missing out on bigger gains.

On the other hand, older people have been found to sometimes use the so-called “maximax heuristic,” which works in the opposite direction. Instead of focusing on avoiding losses, the maximax heuristic seeks to maximize potential to achieve the best possible outcome. In other words, older adults might be more willing to aim for higher rewards despite the higher risk, depending on their goals and circumstances.

To put it more simply, while younger adults seem to be focused on minimizing losses, older adults seem more motivated by maximizing gains. Or think of it this way: Taylor, 30, would prefer to open a local coffee shop, aiming for a steady income and minimizing financial risks. However, Morgan, 64, would be more motivated to invest in a global technology startup, hoping to maximize returns despite the high volatility of such companies.

Both make smart decisions and seek greater rewards based on what matters most to them. This shows that older people’s decision-making is driven by different, but equally complex, motivational factors.

The power of emotions

But that’s not all: one of the main findings of the study is that emotions play a crucial role in decision-making. The scientists reached this conclusion by integrating cognitive and motivational factors into their computer model. They found that older people, who generally experience fewer negative emotions than their younger counterparts, choose less risk-averse strategies in certain situations.

Detailed analysis showed that almost 30% of age-related differences in decision-making could be directly linked to these emotional changes. These data revealed that it is not cognitive decline, but rather emotional and motivational changes that cause older adults to approach risk differently.

Imagine an elderly person deciding whether or not to invest in a grandchild’s startup. While a younger person may examine every potential risk, an older person may focus more on the potential rewards and joy of providing for their family, reflecting a strategy driven by positive emotions and long-term satisfaction instead. than through simple financial prudence.

Understanding that older adults use different, but not simpler, strategies can help design better support systems. This understanding can potentially inform public policies aimed at improving decision-making among older adults (such as personalized health information or tailored retirement planning systems). By recognizing the motivational factors at play, we can develop more effective interventions that respect and leverage older adults’ cognitive strengths.

Advancing intelligence research

Previous research has shown that decision-making under risk is an important manifestation of intelligence. This study contributes to the field of intelligence research by challenging the stereotype that cognitive decline in older adults leads to simpler decision-making in such scenarios.

Instead, it highlights the adaptability and resilience of cognitive processes, showing that older adults can and do use sophisticated strategies. By shedding light on the interplay between cognitive and motivational factors, the study provides new insights into the nature of intelligence across the lifespan and gives scientists valuable insights into the nature of intelligent decision-making .

More information:

Florian Bolenz et al, Older adults select different but not simpler strategies than younger adults when making risky choices, PLOS Computational Biology (2024). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1012204

Provided by Technische Universität Berlin – Science of Intelligence

Quote: Age is just a number: New study shows older people’s decision-making strategies are just as complex as those of younger adults (2024, October 10) retrieved October 10, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.