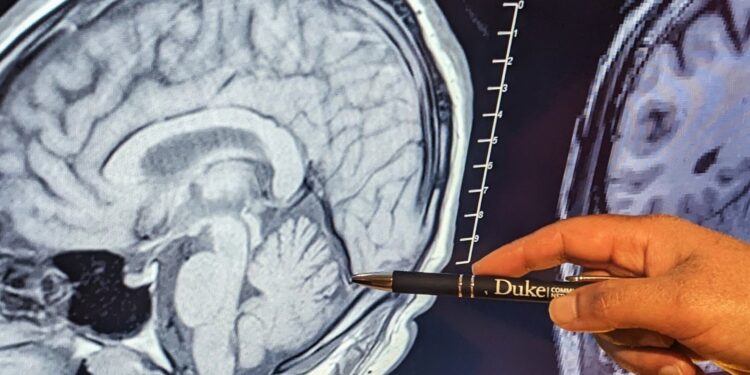

The cerebellum, indicated by a pointer, is the brain within the cerebrum or the small brain. It contains half of the brain’s neurons, packed tightly together. Credit: Dan Vahaba, Duke University

Adults with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have smaller cerebellums, according to new research from a Duke-led brain imaging study.

The cerebellum, a part of the brain well known for helping coordinate movement and balance, can influence emotions and memory, which are affected by PTSD. What is not yet known is whether a smaller cerebellum predisposes a person to PTSD or whether PTSD shrinks the region of the brain.

“The differences were largely in the posterior lobe, where many of the cognitive functions attributed to the cerebellum appear to be located, as well as in the vermis, which is linked to many emotional processing functions,” said Ashley Huggins, Ph. .D., the lead author of the report who helped carry out the work as a postdoctoral researcher at Duke in the laboratory of psychiatrist Raj Morey, MD

Huggins, now an assistant professor of psychology at the University of Arizona, hopes these findings will encourage others to consider the cerebellum as an important medical target for PTSD sufferers.

“If we know which areas are involved, then we can begin to focus interventions such as brain stimulation on the cerebellum and potentially improve treatment outcomes,” Huggins said.

The results, published in Molecular Psychiatryprompted Huggins and his lab to start looking for which comes first: a smaller cerebellum that could make people more susceptible to PTSD, or trauma-induced PTSD that leads to shrinkage of the cerebellum.

PTSD and the “small brain”

PTSD is a mental health disorder caused by experiencing or witnessing a traumatic event, such as a car accident, sexual abuse, or military combat.

Although most people who experience a traumatic experience are spared the disorder, about 6% of adults develop post-traumatic stress disorder, which is often marked by increased fear and reliving the traumatic event.

Researchers have discovered several brain regions implicated in PTSD, including the almond-shaped amygdala, which regulates fear, and the hippocampus, a critical hub for processing memories and transporting them throughout the brain.

The cerebellum (Latin for “small brain”), on the other hand, has received less attention for its role in PTSD.

A cluster of cells the size of a grapefruit that appears to have been awkwardly pinned under the back of the brain as an afterthought, the cerebellum is best known for its role in coordinating balance and choreographing complex movements, like walking. or dancing. But there is much more than that.

“It’s a really complex area,” Huggins said. “If you look at how densely populated it is with neurons compared to the rest of the brain, it’s not surprising that it does a lot more than balance and movement.”

Dense is perhaps an understatement. The cerebellum makes up only 10% of the brain’s total volume, but contains more than half of the brain’s 86 billion nerve cells.

Researchers have recently observed changes in the size of the very compact cerebellum in PTSD. Most of this research, however, is limited either by a small data set (less than 100 participants), broad anatomical limitations, or an exclusive focus on certain patient populations, such as veterans or victims of assault. suffering from PTSD.

Subtle and consistent reductions

To overcome these limitations, Duke’s Dr. Morey, along with more than 40 other research groups as part of a larger data-sharing initiative, pooled their brain imaging analyzes to study PTSD as broadly and universal as possible. The group ended up with images from 4,215 MRI scans of adults, about a third of whom had been diagnosed with PTSD.

“I spent a lot of time looking at the cerebellums,” Huggins said.

Even with automated software to analyze the thousands of brain scans, Huggins manually checked each image to ensure that the boundaries drawn around the cerebellum and its many subregions were accurate. The result of this extensive methodology was a fairly simple and consistent result: PTSD patients had approximately 2% smaller cerebellums.

When Huggins zoomed in on specific areas of the cerebellum that influence emotions and memory, she found similar cerebellar reductions in people with PTSD. She also found that the more severe a person’s PTSD, the smaller their cerebellum.

“Focusing only on a categorical yes or no diagnosis doesn’t always give us the clearest picture,” Huggins said. “When we looked at the severity of PTSD, people with more severe forms of the disorder had even smaller cerebellar volume.”

Targeting the cerebellum for treatment and more research

The findings provide an important first step in determining how and where PTSD affects the brain.

There are more than 600,000 combinations of symptoms that can lead to a PTSD diagnosis, Huggins explained. It will also be important to know whether different combinations of PTSD symptoms have different impacts on the brain.

For now, however, Huggins hopes this work will help others recognize the cerebellum as an important driver of complex behaviors and processes beyond gait and balance, as well as a potential target for New and current treatments for people with PTSD.

“While there are good, effective treatments for people with PTSD, we know they don’t work for everyone,” Huggins said. “If we can better understand what’s happening in the brain, then we can try to incorporate that information to provide treatments that are more effective, longer-lasting and suitable for more people.”

More information:

Smaller total and subregional cerebellar volumes in post-traumatic stress disorder: a mega-analysis by the ENIGMA-PGC PTSD Working Group, Molecular Psychiatry (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41380-023-02352-0. www.nature.com/articles/s41380-023-02352-0

Provided by Duke University

Quote: New study finds that traumatic stress is associated with a smaller cerebellum (January 9, 2024) retrieved January 9, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.