Lost teeth, histology and CT scan reveal exceptionally rapid tooth development in the largest living lizard. Credit: Tea Maho, University of Toronto Mississauga

Kilat, the largest living lizard at the Metropolitan Toronto Zoo, like other members of its species (Varanus komodoensis), truly deserves to be called the Komodo dragon. Its impressive size and the way it looks at you and follows your every move makes you realize that it is an apex predator, much like a ferocious theropod dinosaur.

So it’s no surprise when you look around his enclosure to find that there are lost teeth glistening on the ground, a common find when hunting for Mesozoic theropod dinosaurs. This surprising phenomenon led researchers to study the teeth and feeding behavior of this predator. The Toronto Zoo team collected many lost teeth and allowed the team to undertake this study, and skulls from the Royal Ontario Museum’s skeleton collection were also made available to them.

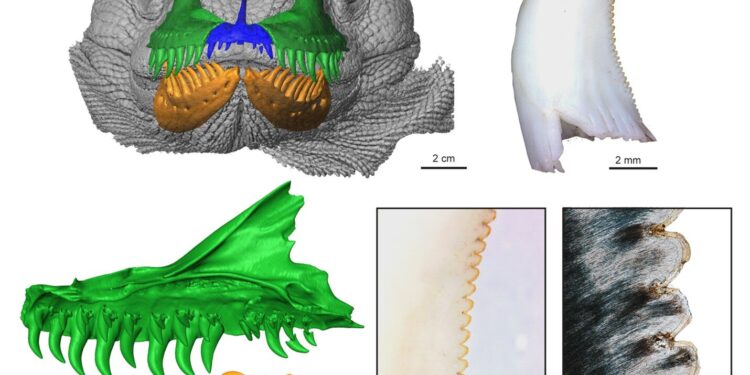

Previous studies have focused on the unique feeding behavior of the Komodo dragon, but have not linked this to its unique dental morphology, development and replacement. The team examined the dentition and jaws of adults and juveniles using a combination of histological analysis and computed tomography (CT) scanning. They found that adult Komodo teeth were strikingly similar to those of theropod dinosaurs, with the adults’ strongly recurved teeth having jagged cutting edges reinforced by dentin cores.

“We were very excited about this discovery because it makes the Komodo an ideal living model organism for studies on the life history and feeding strategies of extinct theropod dinosaurs,” said Dr. Tea Maho, lead author of a paper on this research, published in PLOS ONE.

Kilat, Komodo dragon, 20 years old. Credit: Toronto Zoo

The Komodo dragon, like most other reptiles, including extinct theropod dinosaurs, continually replaces its teeth throughout its life. Histology – a common technique for studying the microstructure of teeth – and X-ray computed tomography of Komodo dragon heads showed that the Komodo dragon retains up to five replacement teeth per tooth position in its jaw.

“Having so many teeth in the jaw at one time is a unique feature among predatory reptiles, and it is only observed in Komodo,” noted Dr. Robert Reisz, co-author of the research paper.

Most other known reptiles have one or at most two replacement teeth in their jaws, including most theropod dinosaurs. Perhaps the most surprising discovery was that Komodos began making new teeth in each dental position every 40 days. This is why there were so many lost teeth in the Komodo dragon enclosure, and this is how new teeth replace old, functioning teeth very quickly. Other reptiles, including most theropod dinosaurs, typically took three months to replace a tooth, sometimes up to a year.

“So if in the wild a tooth breaks during capture of prey or defleshing, no problem, a new one would replace the broken tooth very quickly,” explains Tea Maho.

Because the team had skulls and teeth from both adult and juvenile Komodo dragons, they were also able to discover an interesting correlation between Komodo dragons’ teeth and their feeding behavior. Komodo hatchlings and juveniles have more delicate teeth, not adapted to the typical adult defleshing behavior, and spend most of their time in trees, avoiding adults and feeding primarily on insects and small vertebrates .

As they grow to adult size, the shape of their teeth changes drastically and they eventually descend from trees to become apex predators, capable of attacking and killing anything within their range.

Researchers have also noticed that the front teeth of Komodo adults are either very small or completely absent. This unusual dental morphology correlates well with their tongue-flapping behavior, using the thin, forked, snake-like tongue to search for prey without having to open their mouth.

More information:

Tea Maho et al, Exceptionally rapid dental development and ontogenic changes in the Komodo dragon’s food system, PLOS ONE (2024). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0295002

Provided by University of Toronto

Quote: New research finds adult Komodo teeth are strikingly similar to those of theropod dinosaurs (February 7, 2024) recovered on February 7, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.