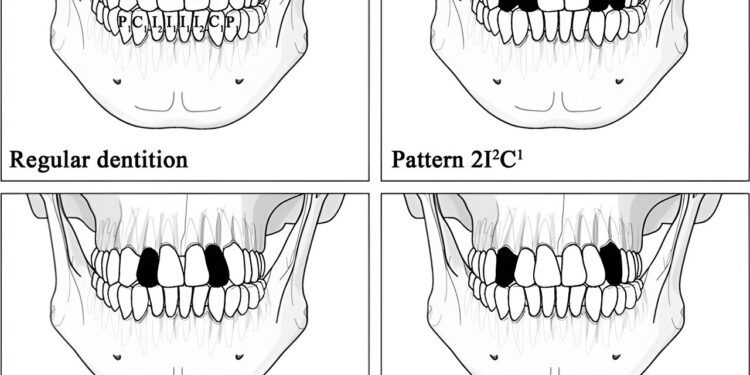

Illustration of regular dentition and tooth removal patterns observed in ancient and contemporary populations of Taiwan. Black teeth indicate their removal. Credit: Archaeological research in Asia (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.ara.2024.100543

A recent study published by archaeologist Yue Zhang and colleagues in Archaeological research in Asia provided detailed information on the practice of tooth removal in Taiwan from the Neolithic to the modern era.

Tooth ablation is the practice of removing healthy teeth. In ancient Taiwan, this practice involved the removal of certain upper front teeth, usually incisors (I) and/or canines (C). This tradition is associated with early Austronesian (AN) communities, which later spread throughout the Asia-Pacific region.

However, until recently, a comprehensive archaeological and ethnographic overview of this practice has been lacking, resulting in a significant gap in knowledge about how the practice developed, why it persisted, and the social and cultural norms surrounding it.

This practice was first observed in Taiwan around 4800 BP, during the Neolithic period (4800-2400 BP). It coincided with the transformation of local hunter-gatherer societies into more sedentary societies. These sedentary societies introduced a new horizon of pottery, domesticated plants (rice and millet), animals, and the first known case of tooth removal.

The most common dental ablation patterns recorded were 2I2C1 and 2I2 (where the number 2 indicates bilateral removal and the superscript indicates the upper tooth and its position). Skeletal remains indicate that tooth removal was practiced equally between the sexes. From its origins along the coast, the practice of tooth removal, burial, and agricultural norms spread and proliferated, even to neighboring regions of the Asia-Pacific.

“The development of the custom of tooth removal in ancient Taiwan aligns with the broader understanding of its Neolithic culture. The coherent pattern of tooth removal (2I2C1) observed in the early Austronesian population of Taiwan is also comparable to patterns found in Austronesian-related cultures throughout Island Southeast Asia. Therefore, the 2I2C1 “Ablation could reasonably be considered a characteristic of ancient Austronesians,” Zhang said.

However, by the end of the Neolithic, a new trend had emerged: men stopped practicing tooth removal as frequently. By 1900 BC, during the Iron Age, the practice of tooth removal had become almost exclusively female.

The reasons for this shift are puzzling. However, Zhang provided a possible explanation for the shift, stating: “The decline in male tooth removal may reflect broader cultural and social changes. As Neolithic materials and culture were fully adapted and evolved into more local expressions during this phase, tooth removal may have been reinterpreted differently.”

While archaeology can provide some information, other information is drawn from ethnographic accounts. Some of the earliest documents that mention tooth removal date from the Chinese Three Kingdoms period (220 AD), others from Dutch newspapers of the 17th century.

However, the most comprehensive ethnographic accounts were collected during the period of Japanese rule (1895–1945), during which surveys of aborigines were conducted (1901–1909). After this period, armed repression in the 1910s eradicated many local traditions, including tooth removal, although some communities still practiced it until the mid-20th century.

These ethnographic accounts detail some of the reasons that led to tooth removal. The reasons were varied and could differ from one group to another. One motivation for tooth removal was aesthetic. Practitioners believed that normal dentition, similar to that of dogs, pigs, and monkeys, was unaesthetic and instead sought to have teeth more like those of mice.

Other motivations were related to commemorative reasons: tooth removal was seen as a test of courage or a way to commemorate the bravery of an ancestor. Some saw it as a right of passage into adulthood, while others thought it was a way to identify a group. Finally, some motivations for tooth removal were practical, such as making it easier for people suffering from lockjaw (from tetanus) to take medicine. Other practical reasons may not have been as useful as once thought.

“Local (Bunun) reports suggest that tooth removal can improve pronunciation. However, the researcher who collected these reports also expressed doubts, noting that people without tooth removal also have good pronunciation. From a functional perspective, removal of the front teeth could affect eating, as these teeth help to cut food, although the (usually) remaining central incisors can compensate somewhat.”

The motivations, method, and age of tooth removal varied. Typically, people in the northern regions of Taiwan preferred to extract teeth using a metal, wooden, or stone hammer. People in the southern regions preferred to extract teeth using one or two wooden or bamboo sticks tied to a tight wire around the tooth.

Once extracted, the cavity was filled with salt or Miscanthus floridulus ash to stop bleeding and prevent inflammation.

These extraction methods, without anesthesia, were used by children aged 6 or 8 and by adults aged 20.

Interestingly, modern ethnographic accounts have also revealed that tooth removal, unlike in the Late Neolithic and Iron Age, was not as female-centric. According to Zhang, “modern ethnographic records suggest that both sexes practiced tooth removal, although the detailed frequency for each sex has not been noted.”

Although the research conducted by Zhang and his colleagues is comprehensive, further research is planned. “Since our study relies primarily on available skeletal evidence from the Neolithic Age, a crucial period for the migration of ancient Austronesian-related populations to large areas.

“Current finds are rare and sometimes geographically concentrated due to preservation conditions and local archaeological work. More skeletal samples are needed to better understand the origins and evolution of tooth removal, as well as how the practice was implemented by Austronesians as they explored and colonized new regions.”

Furthermore, Zhang adds: “The conflict in gender distribution observed in archaeological and historical records versus modern ethnographic accounts also raises intriguing questions for further research.”

More information:

Yue Zhang et al., Ritual Tooth Removal in Ancient Taiwan and Austronesian Expansion, Archaeological research in Asia (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.ara.2024.100543

© 2024 Science X Network

Quote:New Insights into the Origins and Motives of Ritual Tooth Extraction in Ancient Taiwan (2024, August 19) retrieved August 20, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.