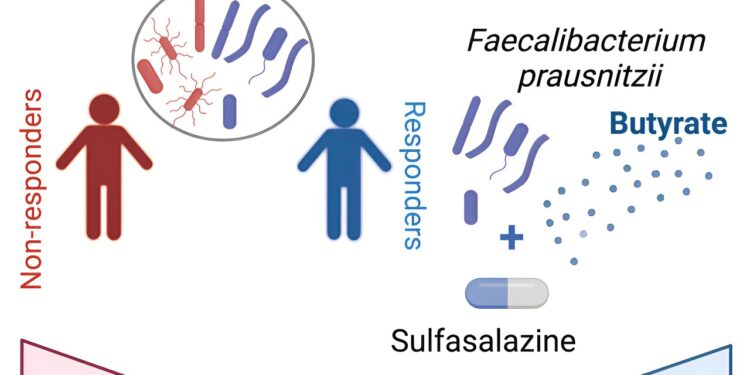

Graphical summary. Credit: Cell Reports Medicine (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2024.101431

Although it is one of the oldest medications used to treat patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and an effective treatment for a related arthritic disease called spondyloarthritis (SpA), Mechanism of action of sulfasalazine is unclear.

Now, researchers at the Jill Roberts Center for IBD and the Jill Roberts Institute for Research in IBD at Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian have determined that the drug works by modulating the activity of a group of gut bacteria most abundant in patients responded to the medication.

These findings resolve a long-standing question: how and why sulfasalazine works for some, but not all, people, and could lead to advances in the treatment of IBD.

In a study published in Cell Reports Medicine, researchers examined IBD-SpA patients treated with sulfasalazine and found that the presence of the gut bacteria Faecalibacterium prausnitzii was a key factor enabling a successful therapeutic response. They determined that sulfasalazine works by positively regulating this bacteria’s production of butyrate, a fatty acid molecule with anti-inflammatory properties.

“These findings provide a means to identify patients with IBD-SpA who may respond to sulfasalazine treatment and also suggest new therapeutic approaches,” said lead study author Dr. Randy Longman, director of the Center. Jill Roberts for IBD and associate professor of medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine and gastroenterologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center.

Co-first authors were Svetlana Lima and Silvia Pires, both postdoctoral research associates in the Longman lab during the study.

It is estimated that more than 2 million Americans suffer from IBD, which includes two distinct disorders: ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. A variety of treatments are available, but their effectiveness is limited, primarily because scientists do not fully understand the immunological processes that trigger and maintain IBD.

IBD frequently coexists with SpA, and sulfasalazine reduces or eliminates symptoms of both conditions in many of these patients. Previous studies have suggested that it works via the gut microbiome, although the precise mechanism has never been clear.

For the study, Longman and his team evaluated 22 patients with IBD-SpA at the Jill Roberts Center for IBD who were starting treatment with sulfasalazine, compared to 11 others who were maintained on standard therapy and used as a control group. Approximately half of patients treated with sulfasalazine showed clinical improvements on a validated measure of disease severity, whereas less than 10% of control patients improved.

In the sulfasalazine group, the team found that the most striking difference between responders and non-responders was the relative abundance of F. prausnitzii and a group of five gut bacteria in their colons. In a separate group of 16 IBD-SpA patients, they confirmed that F. prausnitzii and these other bacteria discriminated responders from non-responders.

In other experiments in an animal model of colitis, the addition of F. prausnitzii to the gastrointestinal tract transformed sulfasalazine non-responders into responders.

F. prausnitzii is known as a particularly potent producer of the anti-inflammatory fatty acid butyrate, long associated with gut health. Although butyrate is made by many gut bacteria as a fermentation product of dietary fiber, the team found that sulfasalazine appears to improve symptoms in SpA-IBD patients by increasing butyrate production, particularly in F. prausnitzii, and not in other butyrate-producing bacteria. tested.

“It is very possible that the effectiveness of sulfasalazine in SpA-IBD patients is limited to specific bacterial species or even strains within a species,” Longman said.

Confirming the key role of butyrate, the team showed that sulfasalazine has no effect in mice when the butyrate receptor on cells, a receptor necessary for butyrate activity, is absent.

The study as a whole suggests that a clinical test for the presence of key bacteria could one day be used to identify patients most likely to benefit from sulfasalazine treatment, Longman said. He added that this approach could be applicable not only to the IBD-SpA combination, but also to either condition separately.

The results also indicate the possibility of therapies that would add F. prausnitzii to the gastrointestinal tract of patients with IBD and SpA to boost responsiveness to sulfasalazine. Oral butyrate supplements are already popular, and gastroenterologists commonly administer butyrate enemas to patients, but these are only partially effective. Longman suspects that bacteria living in the intestinal lining are best placed to deliver this beneficial molecule.

He and his team now plan to further study how F. prausnitzii and its sulfasalazine-enhanced butyrate production calm the immunological storm of IBD-SpA.

More information:

Svetlana F. Lima et al, The gut microbiome regulates the clinical effectiveness of sulfasalazine treatment for IBD-associated spondyloarthritis, Cell Reports Medicine (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2024.101431

Provided by Cornell University

Quote: New knowledge about an old IBD drug could improve treatments (February 20, 2024) retrieved February 20, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.