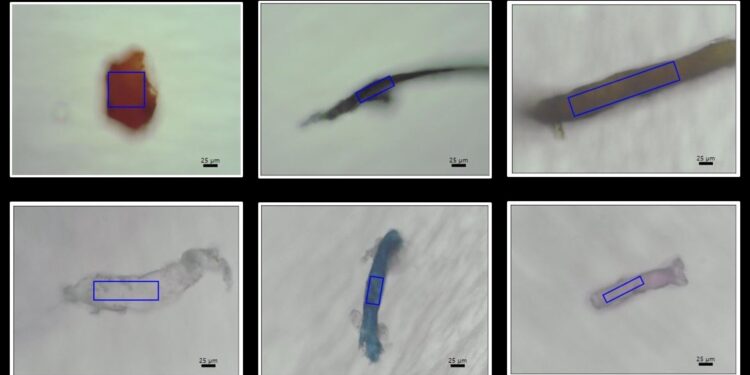

A variety of microplastics extracted from corals off Si Chang Island in the Gulf of Thailand. As seen in color, shape and size, corals consume a wide variety of microplastics, many of which are finer than a human hair. Credit: Kyushu University/Isobe Lab

Japanese and Thai researchers studying microplastics in corals have discovered that all three parts of coral anatomy – surface mucus, tissues and skeleton – contain microplastics. The findings were made possible by a new microplastic detection technique developed by the team and applied to coral for the first time.

The findings could also explain the “missing plastic problem” that has puzzled scientists, where about 70% of plastic waste that has entered the oceans is missing. The team hypothesizes that coral could act as a “sink” for microplastics, absorbing them from the oceans. Their findings were published in the journal Total Environmental Science.

Humanity’s reliance on plastic has brought unprecedented convenience to our lives, but it has caused untold damage to our ecosystem, the causes of which researchers are still beginning to understand. In the oceans alone, an estimated 4.8 to 12.7 million tons of plastic are released into the marine environment each year.

“In Southeast Asia, plastic pollution has become a major problem. In total, nearly 10 million tons of plastic waste are dumped each year, which is one-third of the global total,” said Suppakarn Jandang, assistant professor at the Research Institute of Applied Mechanics at Kyushu University (RIAM) and first author of the study. “Some of this plastic is dumped into the ocean, where it degrades into microplastics.”

To study the problem of plastic pollution in Southeast Asia, RIAM partnered with Thailand’s Chulalongkorn University in 2022 to establish the Center for Ocean Plastic Studies. The international institute is led by Professor Atsuhiko Isobe, who also led the research team behind these latest findings.

The team wanted to study the impact of microplastics on local coral reefs, so they focused their fieldwork on the coast of Si Chang Island in the Gulf of Thailand. The area is known for its small coral reefs and is also a prime location for anthropological studies.

Assistant Professor Suppakarn Jandang (right) and his team prepare to collect coral samples for microplastic analysis. Credit: Kyushu University/Isobe Laboratory

“Coral is made up of three main anatomical parts: the surface mucus, the exterior of the coral body; the tissue, which is the internal parts of the coral; and the skeleton, the hard calcium carbonate deposits they produce. Our first step was to develop a way to extract and identify microplastics from our coral samples,” Jandang continues.

“We subjected our samples to a series of simple chemical washes designed to break down each anatomical layer. After each subsequent layer dissolved, we filtered the contents and then worked on the next layer.”

In total, they collected and studied 27 coral samples from four species. 174 microplastic particles were found in their samples, most of them between 101 and 200 μm in size, about the width of a human hair. Of the microplastics detected, 38% were distributed on the surface mucus, 25% in the tissues and 37% in the skeleton.

Regarding the types of microplastics, the team found that nylon, polyacetylene and polyethylene terephthalate (PET) were the three most prevalent, accounting for 20.11%, 14.37% and 9.77% of the identified samples, respectively.

These new findings also indicate that coral could act as a marine plastic “sink,” sequestering plastic waste from the ocean, in the same way that trees sequester CO2 from the air.

“The problem of missing plastic is a concern for scientists tracking marine plastic waste, but this data suggests that corals could be the source of this plastic shortage,” Jandang says. “Since coral skeletons remain intact after they die, these deposited microplastics can potentially be preserved for hundreds of years. Kind of like mosquitoes in amber.”

Further studies are still needed to understand the full impact of these findings on coral reefs and the global ecosystem.

“The corals we studied this time are distributed all over the world. To get a more accurate picture of the situation, we need to conduct comprehensive studies on a global scale across a wide range of coral species,” Isobe concludes. “We also don’t know the effects of microplastics on the health of corals and the reef community as a whole. Much more work needs to be done to accurately assess the impact of microplastics on our ecosystem.”

More information:

Suppakarn Jandang et al., Possible missing ocean plastic sink: accumulation patterns in reef-building corals in the Gulf of Thailand, The science of the total environment (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.176210

Provided by Kyushu University

Quote:A possible explanation for the ‘missing plastic problem’: New detection technique finds microplastics in coral skeletons (2024, September 20) retrieved September 20, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.