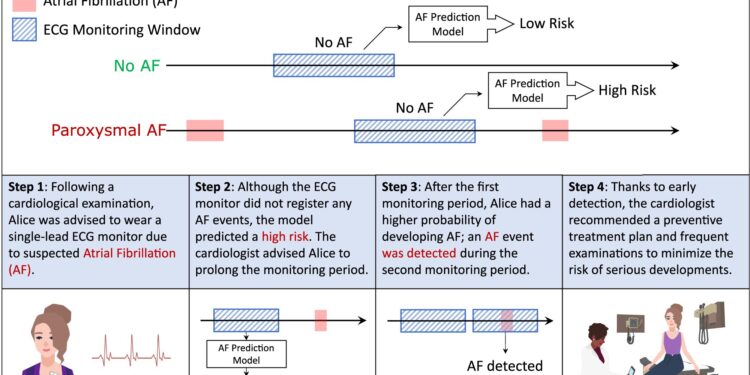

An example of application of the AF prediction model. The figure illustrates the possible outcomes of the AF prediction model when AF is undetected: it can predict low or high risk of future development of AF. In the second part of the figure, we present an example of a potential application. Alice was advised to wear an ECG patch to monitor for potential AF, and although no AF was detected, the model predicted a high risk of AF. Therefore, she was advised to wear a second ECG patch, which ultimately detected AF, allowing her to discuss appropriate treatment with her clinician. Credit: npj Digital Medicine (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41746-023-00966-w

A new artificial intelligence (AI) model designed by Scripps Research scientists could help clinicians better screen patients for atrial fibrillation (or AFib), an irregular, rapid heartbeat associated with stroke and heart disease. heart failure. The model detects tiny variations in a person’s normal heart rhythm that signify a risk of atrial fibrillation, which standard screening tests cannot detect.

The results, described in the review npj Digital Medicine on December 12, 2023, used data from nearly half a million people who had each worn an electrocardiogram (ECG) patch to record their heart rhythms for two weeks – a routine screening test for atrial fibrillation and other heart diseases.

An AI model then analyzed this data to find patterns, other than AFib itself, that distinguished people with AFib from those without it. This new model has the potential to better detect people at risk for atrial fibrillation and ultimately prevent serious side effects of this heart disease, including stroke and heart failure.

“With this new tool, we can better identify patients at high risk for atrial fibrillation for additional testing and interventions,” says lead author Giorgio Quer, Ph.D., director of artificial intelligence at Scripps Research Translational Institute and assistant professor of digital medicine. at Scripps Research. “In the long term, this can help direct the right resources to the right people and potentially reduce the incidence of stroke and heart failure.”

The irregular heartbeat due to atrial fibrillation can cause blood to build up in the heart and form blood clots, which can then contribute to strokes. AFib is also associated with an increased risk of heart failure or death. To prevent these complications in people with known atrial fibrillation, clinicians often prescribe anticoagulants (drugs that prevent blood clots), along with other lifestyle and medical therapies. However, diagnosing atrial fibrillation can be tricky because many people with the condition have only occasional bouts of irregular heart rhythm or few symptoms.

In some people, atrial fibrillation causes heart palpitations, dizziness, shortness of breath, and chest pain. For patients with these symptoms, cardiologists typically record heart rhythms for about ten seconds in their office using a very detailed ECG that includes ten electrodes placed on the body.

If nothing seems abnormal, they recommend continuous monitoring at home for one or two weeks with a simpler, portable ECG patch that has a single electrode. But even over a two-week period, people with very occasional atrial fibrillation may not have an episode picked up by this device.

That’s why Quer, working with iRhythm Technologies (the maker of a wearable EKG patch called ZioXT), set out to find other patterns in the ECG data of people with atrial fibrillation.

“We think the electrical activity of the heart is slightly different in people with atrial fibrillation, but the differences are so subtle that cardiologists can’t look at a printout of heart rhythms and identify these differences,” Quer says.

The team developed a machine learning model to analyze data collected by iRhythm on 459,889 people who wore the company’s at-home ECG patch for two weeks. For each ECG, the model used one day of data containing no atrial fibrillation. However, he was able to distinguish people who later had atrial fibrillation from those who did not.

Even when the researchers incorporated all known risk factors for atrial fibrillation into their own manual models, including demographic data and ECG measurements such as variability between different heartbeats, the machine learning model was more accurate for predict the risk of atrial fibrillation.

“There was a gap between what we could achieve with any known ECG functionality and what the model could achieve,” says Matteo Gadaleta, Ph.D., professional scientific collaborator at the Translational Institute and first author of the article. “It was definitely better.”

Importantly, the model remained accurate for both an older population, who are at higher risk of atrial fibrillation, and for people younger than 55, who are at much lower risk and are generally excluded from general screening for atrial fibrillation.

Although the model is not intended for the diagnosis of atrial fibrillation, it is a first step toward designing a screening test for people at increased risk of atrial fibrillation or experiencing symptoms. This way, they could wear an ECG patch for just one day to determine whether longer tests are recommended. Alternatively, the model could analyze ECG data over one or two weeks to identify patients who, even without atrial fibrillation during that time, should be retested.

“Patients with frequent episodes of atrial fibrillation can be easily identified with an ECG recorded over at least one week,” says Quer. “But this AI model could really help people who have very infrequent episodes of atrial fibrillation, but could still benefit from diagnosis and intervention.”

Quer and his colleagues hope to plan a prospective study and integrate other data sources, such as electronic medical records, into their models to improve them even further.

More information:

Matteo Gadaleta et al, Prediction of atrial fibrillation from home single-lead ECG signals without arrhythmias, npj Digital Medicine (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41746-023-00966-w

Provided by the Scripps Research Institute

Quote: New AI-powered algorithm could better assess risk of common heart disease (December 12, 2023) retrieved December 12, 2023 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.