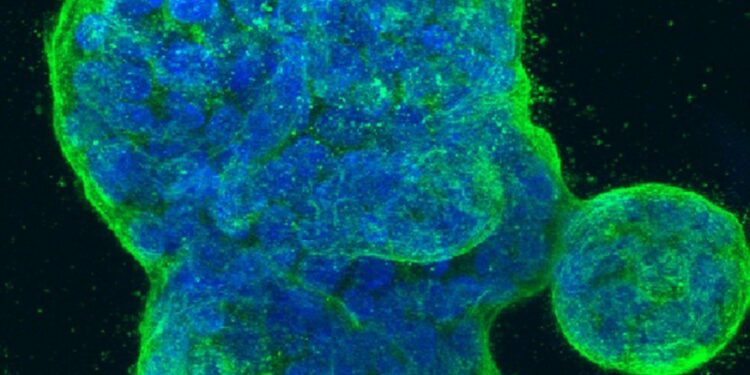

Three-dimensional culture of human breast cancer cells, with DNA stained blue and protein in the cell surface membrane stained green. Image created in 2014 by Tom Misteli, Ph.D., and Karen Meaburn, Ph.D. at the NIH IRP.

With tens of thousands of synthetic chemicals on the market and new products constantly being developed, knowing which ones might be harmful is a challenge for both the federal agencies that regulate them and the companies that use them in their products. Scientists have now found a quick way to predict whether a chemical is likely to cause breast cancer based on its specific characteristics.

“This new study provides a roadmap for regulators and manufacturers to quickly report chemicals that may contribute to breast cancer to prevent their use in consumer products and find safer alternatives,” says Dr. Jennifer Kay, research scientist at the Silent Spring Institute. Dr. Kay is the lead author of a study titled “Application of the Key Characteristics Framework to Identify Potential Breast Carcinogens Using Publicly Available In Vivo, In Vitro, and In Silico Data,” published in Environmental Health Perspectives.

Breast cancer remains the most commonly diagnosed cancer in the United States. Recent data shows rates are increasing among young women, a trend that cannot be explained by genetics. “We need new tools to identify environmental exposures that could contribute to this trend so we can develop prevention strategies and reduce the burden of disease,” says Kay.

Hormonal signals

Kay and his colleagues searched several international and U.S. government databases to identify chemicals that could cause mammary tumors in animals. The databases came from, among others, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), the National Toxicology Program, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and the National Cancer Institute.

Researchers also examined data from the EPA’s ToxCast program to identify chemicals that change the body’s hormones, or endocrine disruptors, in ways that promote breast cancer. The team looked specifically for chemicals that activate the estrogen receptor – a receptor found in breast cells – as well as chemicals that cause cells to produce more estrogen or progesterone, an established risk factor for breast cancer.

Researchers have identified a total of 921 chemicals that may promote the development of breast cancer. Ninety percent of chemicals are those to which people are commonly exposed in consumer products, foods and beverages, pesticides, medications and workplaces.

An analysis of the list revealed 278 chemicals responsible for mammary tumors in animals. More than half of the chemicals cause cells to produce more estrogen or progesterone, and about a third activate the estrogen receptor.

“Breast cancer is a hormonal disease, so the fact that so many chemicals can alter estrogen and progesterone is concerning,” says Kay.

Since DNA damage can also trigger cancer, the researchers searched additional databases and found that 420 of the chemicals on their list damage DNA and change hormones, which which could make them riskier. Additionally, the team’s analysis found that chemicals that cause mammary tumors in animals are more likely to have these DNA-damaging and hormone-disrupting characteristics than those that do not.

“Historically, chemicals that cause mammary tumors in animals were considered the best indicator of their risk of causing breast cancer in humans,” says co-author Ruthann Rudel, director of research at Silent Spring. “But animal studies are expensive and time-consuming, which is why so many chemicals have not been tested. Our results show that screening for these hormonal characteristics with chemicals could be an effective strategy for detecting potential breast carcinogens.”

A roadmap for security

Over the past decade, there has been increasing evidence that environmental chemicals are important contributing factors to the development of cancer. A number of studies in humans have linked breast cancer to pesticides, hair dyes and air pollution. Other studies suggest that exposure to hormone-disrupting chemicals early in life, in the womb or during puberty, may alter breast development in ways that could increase cancer risk later.

However, to observe these associations, scientists must wait until hundreds or even thousands of children and women have been exposed to a chemical and check, often several years later, who develops breast cancer. “It is neither feasible nor ethical to wait this long,” Rudel says. “And that’s another reason why we need better tools to predict which chemicals are likely to lead to breast cancer so we can avoid these exposures.”

The Silent Spring study could have implications for how the EPA evaluates the safety of chemicals. For example, the chemicals identified in the study include more than 30 pesticides that had previously been approved for use by the EPA despite evidence linking these chemicals to breast tumors.

This fall, the EPA proposed a new strategic plan to ensure that pesticides are evaluated for their effects on hormones. The study authors hope their new comprehensive list of chemicals linked to breast cancer, which includes hundreds of endocrine disruptors, will inform the EPA’s plan and better protect the public from harmful exposures.

Other co-authors of the new study include Megan Schwarzman of UC Berkeley and Julia Brody of the Silent Spring Institute.

More information:

Application of the Key Characteristics Framework to identify potential breast carcinogens using publicly available in vivo, in vitro and in silico data, Environmental Health Perspectives (2024). DOI: 10.1289/EHP13233. ehp.niehs.nih.gov/ehp13233

Provided by the Silent Spring Institute

Quote: More than 900 chemicals, many in consumer products and the environment, have breast cancer-causing characteristics (January 10, 2024) retrieved January 10, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.