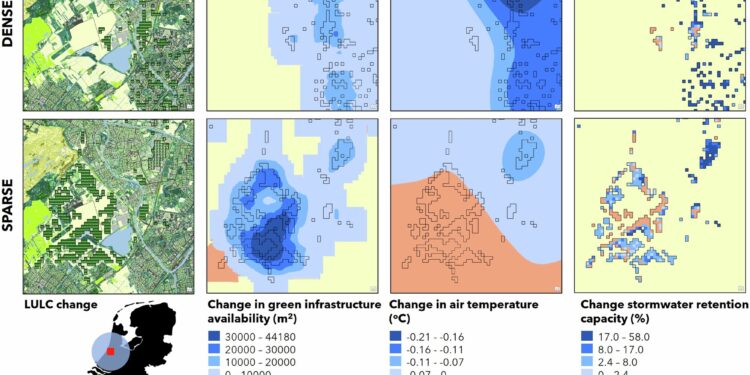

Local-scale impacts of urbanization on ecosystem services. Credit: npj Urban sustainability (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s42949-024-00178-5

By 2050, the Netherlands will need almost two million additional homes. However, housing and associated utility buildings take up already limited space, and the materials needed for construction also have an environmental footprint. With these challenges in mind, Janneke van Oorschot sought to explore where and how best to build.

In her previous research, Van Oorschot had already looked into construction materials for new buildings, with an emphasis on circular use. It also looked at the availability of urban green spaces and the “services” these spaces provide, such as cooling and recreation.

“In this study we combined all these elements,” says Van Oorschot, who is about to complete his doctorate. This research earned him a publication in npj Urban sustainability. Other researchers from the Institute of Environmental Sciences also contributed.

Two scenarios from the Dutch Environmental Assessment Agency (PBL) formed the basis of the research. These scenarios present two versions of what the Netherlands could look like by 2050. “The main question is whether population growth will occur inside or outside cities,” says Van Oorschot. In her research, she refers to densely populated areas (“dense”) and sparsely populated areas (“sparse”).

Hundreds of small cells

By breaking down the PBL projections into hundreds of small cells, the researcher calculated how many materials are needed in each scenario to build the required homes, and how much impact the housing will have on the immediate natural environment in each case.

Its conclusion is that densification of already built-up urban areas is, in most cases, the most efficient in terms of material and land use. This is because houses in cities tend to be smaller and more vertical construction is common. If demolished materials are reused during construction, the material efficiency score improves even further.

LULC composition of areas transformed between 2018 and 2050. Credit: npj Urban sustainability (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s42949-024-00178-5

More green means more cooling

A striking aspect of this “densification scenario” is that additional housing must not come at the expense of green spaces. “On the contrary,” says Van Oorschot, “it is possible to create even more green spaces than before.” This means more cooling, better rainwater absorption and more recreational areas. According to the study, up to 3% more green space could be added.

She gives the city center of Leiden as an example. “This is currently a red dot on the map when it comes to heat. But in places where more housing is built, as well as more green space, this heat spot will clear up by 2050 in projections.”

A tool for policy makers

The study does not claim that building on undeveloped land, such as former agricultural areas, is necessarily a bad idea. However, this shows that material and land use is often higher. However, this shows that the use of materials and land is often higher, as the need for dense construction is less. This translates to larger homes, such as single-family homes. One advantage is that there is usually more space for greenery.

Van Oorschot hopes his research can help policymakers plan housing, utility buildings and green spaces. Thanks to his research, they can now consider both the use of space and materials, in combination with specific local circumstances. In the next phase, the researcher hopes to add more parameters to the model used, such as biodiversity and health impacts.

More information:

Janneke van Oorschot et al, Optimizing green and gray infrastructure planning for sustainable urban development, npj Urban sustainability (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s42949-024-00178-5

Provided by Leiden University

Quote: More housing in cities is possible without sacrificing green spaces, according to a study on sustainable development (2024, October 14) retrieved October 14, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.