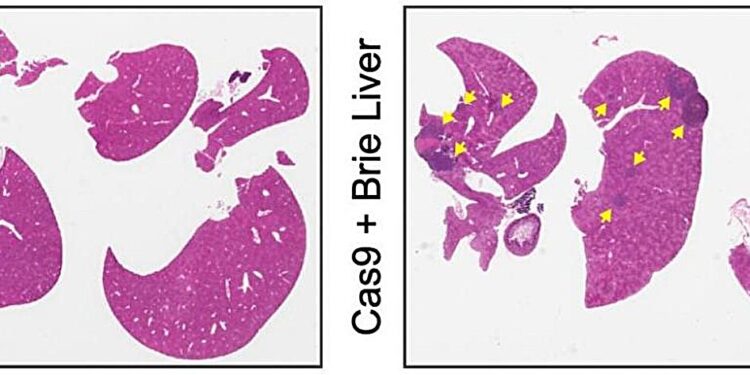

Mouse liver without liver metastases (left) and mouse liver with multiple liver metastases (right, with yellow arrows) developing as a result of genetic deletions of kinases. Credit: Natural cancer (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s43018-023-00704-x

A new study led by researchers at the Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center (HICCC) has identified a crucial factor that can drive tumor cells to spread to the liver. The work, published in the current issue of Natural cancerindicates strategies that could help treat these often recalcitrant tumors.

Many types of cancer can spread or metastasize to tissues other than where they originated, but the liver is one of the worst destinations for them. “The clinical observation is that patients who have liver metastases generally do poorly, (and) they also don’t respond as well to all kinds of therapies,” says Benjamin Izar, HICCC member and lead author. of the new study.

The link between enzymes, cancer and insulin

To try to understand why, Izar and an international team of collaborators looked for factors that might push cancer cells toward the liver. The scientists first generated a library of lab-grown melanoma cells, in which each cell had one of several hundred enzymes deleted from its genome.

Specific targeted enzymes, called kinases, are essential to many aspects of tumor cell biology. By placing the engineered cells into an animal model of melanoma and then looking for metastatic tumors, we identified kinases that might be involved in the spread of the cancer.

Deleting different kinases “does not seem to change the number of metastases in the lungs, but only in the liver,” says Izar. Looking closer, the investigators found that the loss of a kinase called Pip4k2C made melanoma cells particularly likely to colonize the liver.

Coincidentally, work by another group recently suggested that Pip4k2C was involved in the regulation of cellular responses to insulin. Izar’s team hypothesized that the liver’s insulin-rich environment attracted these cells.

Cancer drug raises blood sugar, attracting cancer cells to the liver

The team used CRISPR-Cas9 to delete Pip4k2c from melanoma cells and found that insulin made these cells more sensitive to activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway, which is essential for cancer growth. Based on this knowledge, Izar’s team further hypothesized that using a PI3K inhibitor would shut down the activated pathway, thereby limiting liver metastasis.

However, when they used a PI3K inhibitor to treat mice with Pip4k2c-deleted melanoma cells, they saw an increase rather than a decrease in metastatic burden.

“We found that, yes, we inhibited the PI3K pathway in cancer cells, but we inhibited PI3K more potently in normal liver tissue cells,” says Izar. This raised the animals’ blood sugar levels, which significantly increased insulin levels in the liver, creating an even more fertile ground for cancer cells.

Another series of experiments revealed a way to block this effect, through two different mechanisms. When the mice’s blood sugar levels were kept low, either with a diabetes drug or a ketogenic diet, the engineered melanoma cells were no longer able to seed the liver and the PI3K inhibitor was more effective in preventing diabetes. liver metastases.

Through international collaborations with academic and industrial partners, Izar’s group analyzed molecular profiling data of tumor cells from thousands of melanoma patients and found that the mechanisms discovered in the mouse experiments are likely also at play in humans.

Lowering blood sugar could reduce the spread of cancer to the liver

Izar cautions that the animal and cell culture results do not prove that the same approach would work in humans, but he and his colleagues hope to obtain more data to support a possible clinical trial. “It is conceivable that giving patients with liver metastases a combination of a PI3K inhibitor and hypoglycemic therapy could reduce the liver metastatic burden,” says Izar.

He adds that “we could perhaps also improve the activity of immunotherapies, which are generally less beneficial in patients with liver metastases. So I think there is a reasonable chance that this could eventually be used clinically as well “.

More information:

Meri Rogava et al, Loss of Pip4k2c confers hepatic metastatic organotropism via activation of the insulin-dependent PI3K-AKT pathway, Natural Cancer (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s43018-023-00704-x

Provided by Columbia University

Quote: Liver metastases, metabolism and therapeutic conundrum (February 19, 2024) retrieved February 19, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.