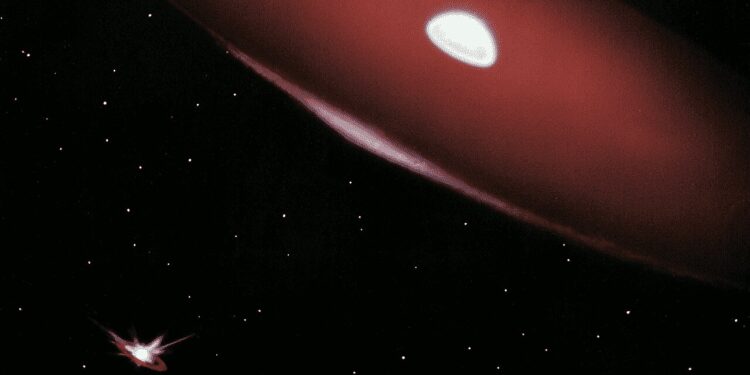

Artist’s rendering of a Be star and its disk (top right) orbiting a faint, hot, bare star (bottom left). Credit: Painting by William Pounds

Scientists working with the powerful telescopes at Georgia State’s Center for High Angular Resolution Astronomy (CHARA) have conducted a study of a group of stars believed to have devoured most of the gas from companion stars in orbit. These sensitive measurements directly detected the faint glow of the cannibalized stars.

The new research, led by postdoctoral research associate Robert Klement, is published in The Journal of Astrophysics. The work identifies new orbits of bare sub-dwarf stars that surround rapidly rotating massive stars, leading to a new understanding of the life trajectories of nearby binary stars.

Working with colleagues at the CHARA Array in Mount Wilson, California, Klement pointed the high-powered telescopes toward a collection of relatively nearby B emission-line stars, or “Be stars” for short. These are rapidly rotating stars thought to harbor unusual orbiting companions.

Be stars probably form during intense interactions between pairs of nearby stars. Astronomers find that many stars occur in such pairs, a trend that is especially true among stars more massive than our Sun. Couples with small separations face a tumultuous fate as they grow older and can reach a similar dimension to their separation.

When this happens, gas from the growing star can pass through the space between the two stars so that the companion can feast on the transferred gas flow. This cannibalization process will eventually rob the mass donor star of almost all of its gas and leave behind the tiny hot core of its former nuclear combustion center.

CHARA Array measurements (red ellipses) of the motion of the bare star (dashed line) that orbits the Be star HR2142 (yellow star) every 81 days. The small black stars are the calculated positions of the stripped companion at the time of our observations. The orbit is circular, but appears elliptical because it is inclined relative to the plane of the sky. The top and right axes show the apparent physical separation in astronomical units (AU, the average Earth-Sun distance), while the bottom and left axes give the angular separation in angular units of milliarcseconds (mas). For comparison, the full Moon in the sky has an angular diameter of about 2 million milliarcseconds. Credit: Robert Klement

Astronomers predicted that the mass transfer flow would spin the companion star and turn it into a very fast rotator. Some of the fastest rotating stars are found as Be stars. Be stars rotate so quickly that some of their gas is thrown out of their equatorial zones to form an orbiting ring of gas.

Until now, this predicted stage in the life of close binary pairs has eluded astronomers because the separations between stars are too small to be seen with conventional telescopes and because the stripped stellar corpses are hidden in the glare of their brilliant companions. However, Georgia State’s CHARA Array telescopes have offered researchers the means to find the bare stars.

The CHARA Array uses six telescopes spread across the summit of Mount Wilson to act as a single, enormous telescope measuring 330 meters in diameter. This gives astronomers the ability to separate light from pairs of stars even with very small angular shifts. Klement also used the MIRC-X and MYSTIC cameras, built at the University of Michigan and the University of Exeter in the United Kingdom, which can record the light signal of very bright and very faint objects close to each other. others.

The researchers wanted to determine whether Be stars had been rotated by mass transfer and whether orbiting host stars were denuded. Klement began a two-year shadowing program at CHARA and his work quickly paid off. He discovered the faint light of stripped companions in nine of the 37 Be stars. It focused on seven of these targets and was able to track the stellar corpse’s orbital movement around the Be star.

“Orbits are important because they allow us to determine the masses of pairs of stars,” Klement said. “Our mass measurements indicate that stripped stars have lost almost everything. In the case of the star HR2142, the stripped star probably went from 10 times the mass of the sun to about one solar mass.”

The six CHARA telescopes are arranged in a Y shape offering 15 baselines ranging from 34 to 331 meters in length and up to 10 possible closing phase triangles. Credit: The Astrophysics Journal (2024). DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/ad13ec

Bare stars were not detected around each Be star, and researchers believe that in some of these cases the corpse transformed into a tiny white dwarf star, too faint to be detected even with the CHARA Array. In other cases, the interaction may have been so intense that the stars merged to become a single, rapidly rotating star.

Klement is now extending the search for bare stars in orbit to Be stars in the southern sky using the Very Large Telescope Interferometer at the European Southern Observatory in Chile.

He also works with Luqian Wang at the Yunnan Observatories in China in research using NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope to detect faint light from stripped companions. Because these corpses are hot, they are relatively brighter in ultraviolet wavelengths that can only be observed with the Hubble Space Telescope.

“This study of Be stars – and the discovery of nine faint companion stars – truly demonstrates the power of CHARA,” said Alison Peck, program director in the Division of Astronomical Sciences at the National Science Foundation, which supports the CHARA Array. “Using the array’s exceptional angular resolution and high dynamic range allows us to answer questions about star formation and evolution that have never been possible to answer before.”

Douglas Gies, director of the CHARA Array, said the research had finally uncovered a hidden key milestone in the lives of close stellar couples.

“The CHARA Array survey of Be stars directly revealed that these stars were created by a global mass transfer transformation,” Gies said. “We now see, for the first time, the result of the stellar feast that led to the bare stars.”

More information:

Robert Klement et al, The CHARA Array interferometric program on the multiplicity of classical Be stars: new detections and orbits of stripped subdwarf companions, The Astrophysics Journal (2024). DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/ad13ec

Provided by Georgia State University

Quote: Learn the trick to finding cannibalized stars (February 9, 2024) retrieved February 9, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.