Credit: CC0 Public domain

Bees help pollinate more than a third of the world’s crops, contributing an estimated value of US$235 billion to US$577 billion to global agriculture. They also face myriad stresses, including pathogens and parasites, loss of suitable food sources and habitats, air pollution, and climate-driven extreme weather events.

A recent study published in Scientific reports identified another important but little-studied pressure on bees: the “inert” ingredients of pesticides.

In the United States, all pesticide products contain active and inert ingredients. Active ingredients are designed to kill or control a specific insect, weed, or fungus and are listed on product labels. All other ingredients (emulsifiers, solvents, carriers, aerosol propellants, fragrances, colorants, etc.) are considered inert.

The new study exposed bees to two treatments: isolated active ingredients from the fungicide Pristine, used to control fungal diseases in almonds and other crops, and the entire Pristine formulation, including inert ingredients. The results were quite surprising: the entire formulation impairs the bees’ memory, while the active ingredients alone do not.

This suggests that the inert ingredients in the formula were actually what made Pristine toxic to bees, either because the inerts were toxic on their own or because their combination with the active ingredients made the active ingredients more toxic. As a social scientist interested in bee declines, I believe that, in one way or another, these findings have important implications for pesticide regulation and bee health.

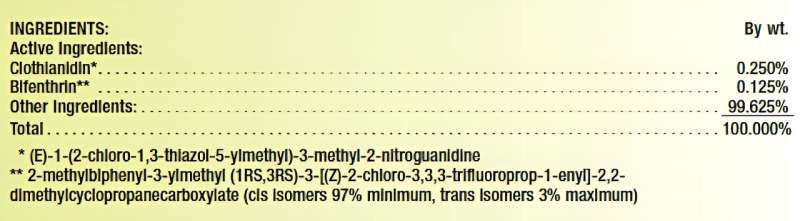

Example of a pesticide ingredient label from an EPA training guide, showing that only 0.375% of ingredients are disclosed and tested for bee safety. Credit: EPA

What are inert ingredients?

Inert ingredients have various functions. They can extend the shelf life of a pesticide, reduce risks to people who apply it, or help a pesticide work better. Some inerts, called adjuvants, help pesticides adhere to plant surfaces, reduce pesticide drift, or help active ingredients better penetrate a plant’s surface.

The label “inert,” however, is a colloquial and misnomer. As the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency notes, inerts are not necessarily inactive or even nontoxic. In fact, pesticide users sometimes know very little about how inerts work in a pesticide formulation. This is partly because they are regulated very differently from active ingredients.

Measuring the effects of bees

Under the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act, or FIFRA, the EPA oversees the regulation of pesticides in the United States. To register a pesticide product for outdoor use, chemical companies must provide reliable risk assessment data on the toxicity of active ingredients to bees, including the results of an acute bee contact test.

The acute contact test tracks the response of bees to a pesticide application over a short period of time. It also aims to establish the dose of a pesticide that will kill 50% of a group of honey bees, a value known as the LD50. To determine the LD50, scientists apply the pesticide to the bees’ midsections, then observe the bees for 48 to 96 hours for signs of poisoning.

In 2016, the EPA expanded its data requirements by requiring an acute oral toxicity test for bees, in which adult bees are fed a chemical, as well as a larval test of honeybees of 21 days following the larvae’s reaction to an agrochemical from egg to emergence. like adult bees.

These tests all help the agency determine the potential risk an active ingredient may pose to bees, along with other data. Based on information from these various tests, pesticides are labeled as nontoxic, moderately toxic, or highly toxic.

A chemical black box

Despite these rigorous tests, much is still unknown about the safety of pesticides for bees. This is especially true for pesticides that have sublethal or chronic toxicities, in other words, pesticides that do not cause immediate death or obvious signs of poisoning but have other important effects.

This lack of knowledge about sublethal and chronic effects is problematic because bees may be exposed repeatedly and over long periods to pesticides present on flower nectar or pollen, or to pesticide contamination that accumulates in hives. They can even be exposed by the acaricides that beekeepers use to control varroa, a devastating parasite of bees.

To compound the problem, the symptoms of sublethal exposure are often more subtle or take longer to appear than those of acute or fatal toxicity. Symptoms may include abnormal foraging and learning ability, decreased queen egg laying, wing deformity, stunted growth, or decreased colony survival. The EPA does not always require chemical companies to perform the tests that can detect these symptoms.

Inert ingredients add another level of mystery. Although the EPA reviews and must approve all inert ingredients, it does not require the same toxicity testing as for active ingredients.

Indeed, according to FIFRA, inert ingredients are protected as trade secrets or confidential business information. Only the total percentage of inert ingredients is required on the label, often grouped together and described as “other ingredients.”

Credit: Lilla Frerichs/public domain

Sublethal weapons

Growing evidence suggests that inerts are not as harmless as their name suggests. For example, exposure to two types of adjuvants – organosilicon and non-ionic surfactants – can impair the learning performance of bees. Bees rely on their learning and memory functions to gather their food and return to the hive. The loss of these crucial skills can therefore endanger the survival of a colony.

Inerts can also affect bumblebees. In a 2021 study, exposure to alcohol ethoxylates, a coformulant of the fungicide Amistar, killed 30% of bees exposed to it and caused a number of sublethal effects.

Although some inerts may be non-toxic on their own, it is difficult to predict what will happen when they are combined with active ingredients. Research has shown that when two or more agrochemicals are combined, they can become more toxic to bees than when applied alone. This is called synergistic toxicity.

Synergy can also occur when inerts are combined with pesticides. Another 2021 study showed that non-toxic adjuvants by themselves led to increased colony mortality when combined with insecticides.

A better testing strategy

Growing evidence on inert toxicity highlights three key changes that could better support bee health and minimize their exposure to potential stressors.

First, pesticide environmental risk assessments could test the entire pesticide formulation, including inert ingredients, to provide a more complete picture of a pesticide’s toxicity to bees. This is already done in some cases, but could be required for all outdoor uses where bees may be exposed.

Second, inerts could be identified on product labels to enable independent research and risk assessment.

Third, more testing may be needed to assess long-term sublethal effects of pesticides on bees, such as learning disabilities. Such research would be particularly relevant for pesticides applied to flowering crops or flowers that attract bees.

Researchers and environmental groups have been advocating for such changes since at least 2006. However, because pesticide regulations are dictated by federal law, the changes require congressional action. This would pose a policy challenge, as it would increase the regulatory burden on the chemical industry.

Nonetheless, growing concerns about bumblebee declines and significant annual colony losses among beekeepers argue for a more cautious approach to pesticide regulation. With a growing global population and increasingly strained food supplies, it is more important than ever to support the contribution of bees to agriculture.

More information:

Nicole S. DesJardins et al, “Inert” coformulants of a fungicide cause acute effects on the learning performance of honey bees, Scientific reports (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-023-46948-6

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()

Quote: “Inert” ingredients in pesticides could be more toxic to bees than scientists thought (December 5, 2023) retrieved December 5, 2023 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.