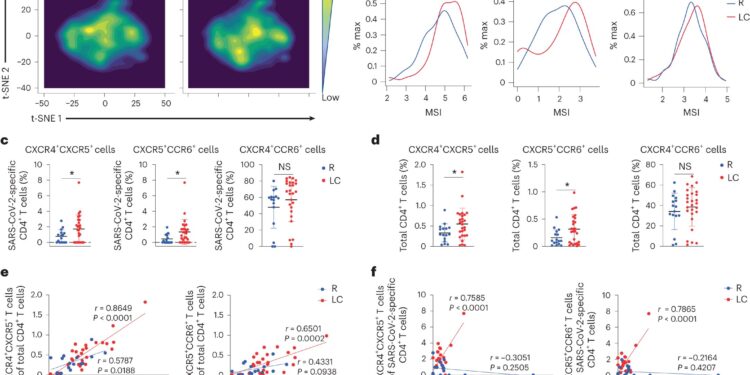

CD4 specific to SARS-CoV-2+ T lymphocytes from individuals with CL preferentially express homing receptors associated with migration to inflamed tissues. Credit: Natural immunology (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41590-023-01724-6

People with long COVID have dysfunctional immune cells that show signs of chronic inflammation and faulty movement in organs, among other unusual activities, according to a new study led by scientists at the Gladstone Institutes and UC San Francisco (UCSF).

The team analyzed immune cells and hundreds of different immune molecules in the blood of 43 people with and without long COVID. They looked particularly deeply into the characteristics of each person’s T cells, immune cells that help fight viral infections but can also trigger chronic inflammatory diseases.

Their conclusions, which appear in Natural immunology, support the hypothesis that long COVID could involve low-level viral persistence. The study also reveals a mismatch between T cell activity and other components of the immune system in people with long-term COVID-19.

“Our findings provide a critical first step in understanding what is happening with T cells in long COVID,” says lead author Nadia Roan, Ph.D., principal investigator at Gladstone and professor at UCSF. “This opens the way to answering current questions about the different types of long COVID, the mechanisms that cause them, and how to treat and prevent them.”

A blank group to study

Long COVID, also known in the medical community as “post-acute sequelae of COVID” or PASC, is broadly defined as symptoms that persist or appear after initial infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

The trajectory of long COVID can vary greatly between individuals; some have initial COVID symptoms that never go away, some have symptoms that come and go, and still others have new symptoms that appear weeks or months after their viral infection. Additionally, vaccination status and subsequent infections may impact long-term COVID risk and disease progression.

“It’s a very heterogeneous condition,” says Roan. “There is a diverse mix of long COVID cases, which makes it difficult to understand what is happening. That’s why it was so important to eliminate some of this variability. We analyzed and compared a set of blank samples that are not complicated by the effects of vaccination or reflux-infection, which can affect T cells and other immune responses.”

Roan’s group partnered with researchers at UCSF, including infectious disease experts Michael Peluso, MD, and Timothy Henrich, MD, who are part of a multidisciplinary team conducting an observational COVID study called LIINC , short for Long-term Impact of Infection With Novel Coronavirus. .

The study follows a cohort of people who were infected once with COVID in 202 and were not vaccinated or reinfected over the next eight months. Those who consistently had symptoms throughout the study period were classified as having long-term COVID, while those who had no symptoms after their initial infection were classified as the control group.

To study participants’ blood collected eight months after COVID infection, the team used six different technologies, including one they had previously implemented to deeply interrogate T cell function in the context of COVID-19. human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. The technique, called CyTOF, measures the levels of different molecules on the surface or inside of T cells.

Several key markers of long COVID

While the overall number of T cells and the number of T cells that react specifically with the SARS-CoV-2 virus were similar between people with long COVID and those who recovered without lingering symptoms, the researchers identified several significant differences. Notably, a subset of T cells called CD4 T cells, which are responsible for overall coordination of immune responses, were in a more inflammatory state in people with long COVID.

“Not everyone with long COVID had these pro-inflammatory cells, but we only saw them in the long COVID group,” says Kailin Yin, Ph.D., a postdoctoral researcher in the Roan lab and co-first author of the study. “This highlights the idea that there is not just one uniform thing that characterizes all individuals with long COVID.”

In another subset of T cells called CD8 T cells, which normally kill cells infected by viruses or bacteria, researchers observed signs of exhaustion preferentially in people with long COVID. Interestingly, these signs were only observed in T cells that recognize the SARS-CoV-2 virus, and not in the broader population of CD8 T cells.

“Such exhaustion is typically seen in chronic viral infections such as HIV, and means that the T cell branch of the immune system stops responding to a virus and no longer kills infected cells,” explains Peluso, an assistant professor in the department. of Medicine from UCSF and co. -first author. “This finding is consistent with some hypotheses that long COVID, or at least some cases, are caused by persistent infections with the SARS-CoV-2 virus.”

The team also discovered an unusually high number of “tissue” T cells, which are T cells that can migrate to tissues throughout the body. This was observed not only by CyTOF, but also by two other technologies, including one that monitors individual cells for thousands of different proteins they are capable of producing.

“It was really interesting because in other studies we are doing in mice, we are also seeing that high levels of tissue receptors are associated with behavioral changes after recovery from SARS-CoV-2 infection “, explains Roan. “In this current study, we are not looking at specific tissues, but our results indirectly suggest that in cases of long COVID, something is happening in the tissues, recruiting T cells to migrate there.”

Finally, researchers showed that in people with long-term COVID-19, levels of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 are unusually high and do not synchronize as they usually do with T cell levels who fight the virus.

“This finding suggests that during a long period of COVID, there is a breakdown in coordination between different branches of the immune system,” says Henrich, a professor in the UCSF Department of Medicine.

It is important to note that the new study was not designed to test potential treatments for long COVID or to assess the feasibility of using T cell markers as a diagnostic. But, says Roan, this opens new avenues to explore in this direction. His team is already planning future experiments on T cells found in specific tissues from people with long COVID and will examine how antiviral and anti-inflammatory drugs might change the characteristics of T cells associated with the disease.

“In the long term, testing interventions will be essential,” says Roan. “With a lot of these associations related to long COVID, we don’t know what’s the chicken and what’s the egg until we test the treatments.”

More information:

Kailin Yin et al, Long COVID manifests as T cell dysregulation, inflammation, and uncoordinated adaptive immune response to SARS-CoV-2, Natural immunology (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41590-023-01724-6

Provided by Gladstone Institutes

Quote: Study: In patients with long COVID, immune cells do not follow the rules (January 11, 2024) retrieved January 11, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.