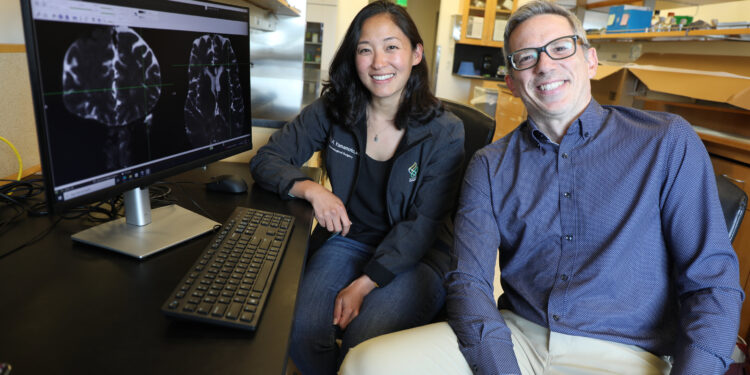

Erin Yamamoto, MD, and Juan Piantino, MD, are among the co-authors of a new study from Oregon Health & Science University that used imaging in neurosurgery patients to definitively reveal the existence of pathways elimination of waste in the human brain known as the glymphatic system. Credit: OHSU/Christine Torres Hicks

Scientists have long theorized about a network of pathways in the brain thought to remove metabolic proteins that would otherwise build up and potentially lead to Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia. But until now, they had never definitively revealed this network in humans.

A study involving five patients undergoing brain surgery at Oregon Health & Science University provides for the first time imaging of this network of perivascular spaces (fluid-filled structures along arteries and veins) in the brain.

“No one has shown this before,” said lead author Juan Piantino, MD, associate professor of pediatrics (neurology) in the OHSU School of Medicine and faculty member in the Neuroscience Section of the OHSU School of Medicine. Papé Family Pediatric Research Institute of OHSU.

“I’ve always been skeptical about this myself, and there are still many skeptics who still don’t believe it. That’s what makes this discovery so remarkable.”

The study is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The study combined the injection of an inert contrast agent with a special type of magnetic resonance imaging to discern cerebrospinal fluid flowing along distinct pathways in the brain 12, 24 and 48 hours after the surgery. By definitively revealing the presence of an efficient waste disposal system in the human brain, the new study supports the promotion of lifestyle measures and medications already developed to maintain and enhance it.

“This shows that spinal fluid doesn’t enter the brain randomly, like if you put a sponge in a bucket of water,” Piantino said. “It goes through these channels.”

More than a decade ago, scientists at the University of Rochester first proposed the existence of a network of waste elimination pathways in the brain, similar to the body’s lymphatic system, which is part of the immune system. These researchers confirmed this using real-time imaging of the brains of living mice. Because of its reliance on glial cells in the brain, they coined the term “glymphatic system” to describe it.

However, scientists have not yet confirmed the existence of the glymphatic system through imaging in humans.

Pathways revealed in patients

The new study examined five OHSU patients who underwent neurosurgery to remove brain tumors between 2020 and 2023. In each case, the patients consented to having an inert gadolinium-based contrast agent injected by a lumbar drain used as part of the normal surgical procedure. for tumor removal. The tracer would be transported with the cerebrospinal fluid to the brain.

Subsequently, each patient underwent magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI, at different times to trace the spread of cerebrospinal fluid.

Rather than spreading evenly through brain tissue, the images revealed fluid moving along pathways, through perivascular spaces in clearly defined channels. Researchers documented this finding with a specific type of MRI known as fluid-attenuated inversion recovery, or FLAIR.

This type of imaging is sometimes used following the removal of brain tumors. It turns out that this also revealed tracer gadolinium in the brain, unlike standard MRI sequences.

“That was the key,” Piantino said.

“You can actually see the dark perivascular spaces in the brain become bright,” said co-senior author Erin Yamamoto, MD, a neurological surgery resident at the OHSU School of Medicine. “It was quite similar to the imaging shown by the Rochester group in mice.”

Eliminate waste from the brain

Scientists believe that this network of pathways effectively rids the brain of metabolic waste generated by its energy-intensive work. The waste products include proteins such as amyloid and tau, which form clumps and tangles in brain images of Alzheimer’s patients.

Emerging research suggests that medications may be helpful, but much of the focus on the glymphatic system has focused on lifestyle-based measures to improve sleep quality, such as maintaining a sleep schedule. regular sleep, establishing a relaxation routine and avoiding screens. bedroom before going to bed. Researchers believe that a well-functioning glymphatic system efficiently transports protein waste to veins exiting the brain, particularly at night during deep sleep.

“People thought these perivascular spaces were important, but it was never proven,” Piantino said. “Now it is.”

The authors credited the late Justin Cetas, MD, Ph.D., who initiated the study as an OHSU neurosurgeon before leaving OHSU to become chairman of neurological surgery at his alma mater, the Center for health sciences from the University of Arizona in Tucson. He died in a motorcycle accident in 2022.

More information:

Piantino, Juan, The perivascular space is a conduit for cerebrospinal fluid flow in humans: a proof-of-principle report, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2024). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2407246121. www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.2407246121

Provided by Oregon Health and Science University

Quote: Imaging in neurosurgery patients reveals brain waste disposal pathways for the first time (October 7, 2024) retrieved October 7, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.