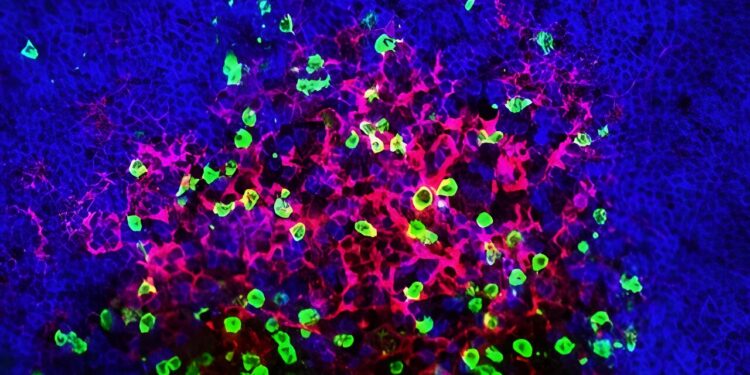

Recall germinal centers formed in response to secondary infection generate a second line of defense, repelling memory B cells in favor of naive cell formation. Credit: Rockefeller University

Some infectious diseases, like COVID or the flu, are constantly evolving, transforming just enough to outsmart our immune systems and reinfect us repeatedly. But subsequent reinfections often do not lead to the most serious consequences, and for good reason.

Upon first exposure to a pathogen, our immune system produces specially trained B cells, which have learned to identify and eliminate the virus. Later, these B cells remain primed and ready to produce powerful booster antibodies.

Scientists have long thought that the body eventually clears these types of infections primarily by resetting old immune cells: refining those previously formed in the germinal centers, which are the specialized structures in our lymph nodes and spleen where B cells learn to identify and eliminate threats. .

But recent work suggests that “germinal recall centers” – those formed during re-exposure – actually generate a different second line of defense. Relying largely on naive, untrained B cells, these reactivated centers focus on developing entirely new antibodies, while experienced B cells spring straight into action.

A new study in Immunity explains how this two-tiered system benefits the immune response, with results that have implications for vaccine boosting strategies.

“We studied the underlying principles that explain how the body responds to repeated exposures, whether it’s a vaccine or a virus, and how germinal recall centers shape that response,” explains Dr. first author Ariën Schiepers, graduate student in Gabriel Victora’s laboratory.

For the study, Victora, Schiepers and colleagues examined mice repeatedly immunized with the same antigen and assessed the antigen-binding abilities of the booster B cells. What they found was that existing antibodies, derived from B cells that had resisted the first infection, actively blocked B cells with overlapping specificities from entering recall germinal centers. When they enhanced the mouse models with variants of the original virus, they discovered why this system made sense.

In response to a viral variant, recall germinal centers guided naive B cells toward the new antigenic target. This prevents the immune system from investing in B cells from a previous infection and repeatedly producing antibodies targeting a missing virus.

“It’s an elegant feedback system, with antibodies generated in the first response helping to form new antibodies against the variant,” says Schiepers. “Germinal recall centers are like librarians who add new titles to the immune system’s library, ensuring that it doesn’t just reach for the same old book over and over again.”

The results suggest implications for booster shots. While traditional boosters work well for childhood vaccines by increasing antibody levels, the approach becomes more complex as viruses evolve. Boosting with a variant antigen can reduce overlap with previous antibodies and allow the immune system to better target new variants.

“This demonstrates exactly why there is a real advantage in strengthening against a variant,” says Schiepers.

More information:

Ariën Schiepers et al, Opposing effects of pre-existing antibody help and memory T cells on germinal recall center dynamics, Immunity (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.immuni.2024.05.009

Provided by Rockefeller University

Quote: Here’s why B cells benefit from booster shots (October 3, 2024) retrieved October 3, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.