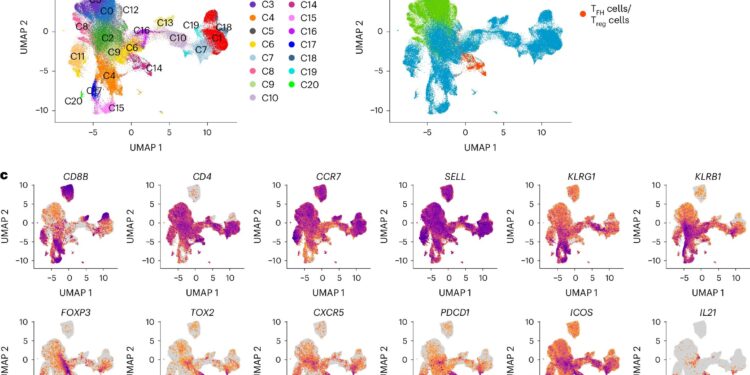

scGEX and TCR profiling captures diverse T cell phenotypes in blood and lymph nodes after influenza vaccination. Credit: Natural immunology (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41590-024-01926-6

Researchers at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine have discovered why the flu vaccine may be ineffective. They found that a specific type of immune cell, called follicular helper T cells, indirectly controls the anti-flu response.

These helper cells often “see” the wrong parts of the virus, likely leading to less effective immunity. The findings, which could guide better vaccine design, were published today in Natural immunology.

“The annual flu vaccine provides some level of protection, but it could be improved,” said co-senior author Paul Thomas, Ph.D., of St. Jude’s Department of Host-Microbe Interactions. “We found that the current formulation of the flu vaccine could likely be improved by focusing on the surface proteins of the flu and excluding the internal proteins of the virus that distract the immune system.”

The results showed that the annual flu vaccine boosts the immune response of vaccinated people, but often not against the most beneficial proteins. The best anti-flu responses target the two flu surface proteins, hemagglutinin and neuraminidase, which change from year to year.

Scientists try to adapt the vaccine each year to account for new surface proteins of dominant flu strains, while the rest of the formulation remains constant. The less-than-ideal immune responses were caused by the vaccine targeting unchanging internal proteins, rather than the more beneficial surface proteins.

“In the current standard flu vaccine, we have this mix of other proteins that we may not need,” Thomas said. “New vaccine formulations should focus the T cell response only on the surface proteins. A simple way to do that is to give the immune cells only those surface proteins to look at, removing the other off-target peptides.”

Lymph node examination reveals lack of immunity

Previous research has shed light on why the flu vaccine has such variable effectiveness, but this study provides a much clearer mechanism. The ideal immune response to the flu involves antibodies. Antibodies bind to targeted proteins to prevent their function and attract immune cells. B cells make antibodies, but they don’t decide which target to target.

Another group of immune cells, called follicular helper T cells, activate B cells in the lymph nodes. This study is the first to offer a high-resolution perspective of helper cells taken from the lymph nodes of people who received the flu vaccine, revealing new insights into how these T cells direct effective immunity against the flu, or not.

“Most studies focus on blood, which is easy to collect but not where the main T-cell response occurs,” said co-first author Stefan Schattgen, Ph.D., of St. Jude’s Department of Host-Microbe Interactions. “We were able to get a better view by looking directly at the lymph nodes over time.”

To study the immune response to vaccination, the scientists examined lymph node samples from a small group of study participants over two years. The researchers identified the fragments of viral proteins to which the follicular helper T cells responded, revealing their preference for internal proteins.

“We found that a large group of follicular helper T cells are responding to the same proteins they see every year, instead of targeting the surface proteins that we’re updating and want them to target,” Thomas said.

Locking the defective response in the lymph node

The researchers documented how immune cells in lymph nodes respond to the vaccine, contrasting with previous research and revealing a new element of the mechanism underlying the vaccine’s poor performance.

“In the blood, we only see a small, brief anti-influenza T-cell response, but in the lymph nodes, it can persist for months,” Schattgen said. “This ‘locks’ the anti-influenza immunity. So if we start an immune response against the wrong target, it can get ‘stuck’ on that internal protein instead of the new surface proteins.”

The results show that the effectiveness of the annual flu vaccine can be hampered by an immune response to the wrong proteins, those in the vaccine that are carried over from year to year. Maintaining this incorrect immunity over the long term prevents the body from creating new, more effective antibodies.

This reflects a well-known immunological phenomenon called antigenic original sin or imprinting, when a person develops an inappropriate immune response to an influenza infection because of previous exposure to influenza.

“We are finally coming to understand the underlying mechanism of antigenic original sin,” Thomas said. “Robert Webster suggested many years ago that the process involves B cells. We have now shown that follicular helper T cells are likely part of the imprinting process that forces B cells to preferentially recall a memory response.”

With knowledge gained about the factors that make the flu vaccine less effective in some people, researchers hope to find ways to use this new knowledge to increase the effectiveness of the vaccine.

“It’s fascinating that we continue to learn a lot about how flu vaccines affect the human immune response,” Thomas said. “And it’s exciting to show that there are still new ways to improve these vaccines and provide better protection.”

More information:

Stefan A. Schattgen et al., Influenza vaccination stimulates maturation of the human T follicular helper cell response, Natural immunology (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41590-024-01926-6

Provided by St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital

Quote:Helper T cells could be key to improving annual flu vaccines (2024, August 20) retrieved August 20, 2024, from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.