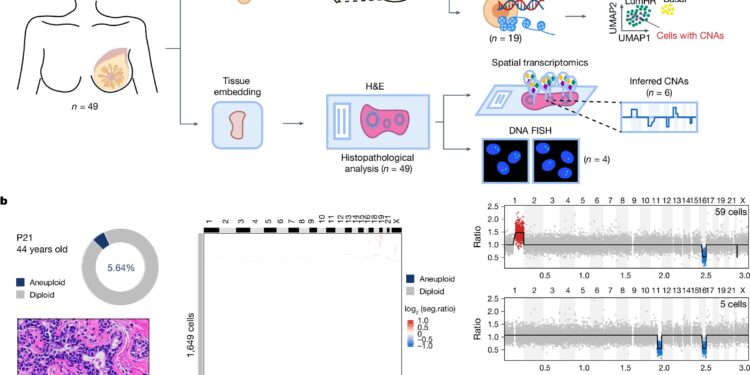

Study overview and data from an individual woman. Credit: Nature (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-08129-x,

A new study led by researchers at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center reveals that in healthy women, some breast cells that otherwise appear normal may contain chromosomal abnormalities typically associated with invasive breast cancer. The results challenge conventional wisdom about the genetic origins of breast cancer, which could influence methods of early cancer detection.

The study, published today in Naturefound that at least 3% of normal breast tissue cells from 49 healthy women contain gain or loss of chromosomes, a condition known as aneuploidy, and that they grow and accumulate with age. This raises questions about our understanding of “normal” tissues, according to lead researcher Nicholas Navin, Ph.D., chair of systems biology.

As researchers continue to develop earlier detection methods using molecular diagnostics as well as ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and biopsies, these findings pose a challenge and highlight the potential risk of false positive identification, because the cells can be mistaken for invasive breast cancer.

“A cancer researcher or oncologist seeing the genomic image of these normal breast tissue cells would classify them as invasive breast cancer,” Navin said.

“We have always been taught that normal cells have 23 pairs of chromosomes, but this seems inaccurate because all of the healthy women we analyzed in our study had irregularities, which raises the very provocative question of when cancer actually occurs.”

The study builds on Navin’s previous work on the Human Breast Cell Atlas, which profiled more than 714,000 cells to generate a comprehensive genetic map of normal breast tissue at the cellular level.

For the current study, researchers examined samples from 49 healthy women with no known diseases undergoing breast reduction surgery. They studied chromosomal copy number changes in normal breast tissue compared to clinical data in breast cancer.

Aneuploid cells in breast tissue from 49 disease-free women and metadata correlations. Credit: Nature (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-08129-x,

Using single-cell sequencing and spatial mapping, the researchers specifically studied breast epithelial cells. Navin points out that epithelial cells, which line and cover the inside and outside of the body, are thought to cause cancer.

Researchers reported that a median of 3.19% of epithelial cells in these normal breast tissues were aneuploid and more than 82.67% had expanded copy number changes commonly found in breast cancers. invasive. Interestingly, a woman’s age is significantly correlated with the frequency of aneuploid cells and the number of copy number changes, with older women accumulating more of these cellular changes.

The most common changes were extra copies of chromosome 1q and losses of chromosomes 10q, 16q and 22, commonly seen in invasive breast cancers. Previous studies have identified specific genes in these regions that are also associated with breast cancer, according to Navin.

The data reveal that these aneuploid cells represent the two known cell lineages of the mammary gland, which have distinct genetic signatures that can be estrogen receptor (ER) positive or negative. One lineage exhibited copy number changes similar to those in ER-positive breast cancers, while the other appeared to exhibit events consistent with ER-negative breast cancers, highlighting their potentially different origins.

Navin notes that this is a report on rare aneuploid cells found in the normal population and that further longitudinal studies are needed to identify potential risk factors, if any, that may lead to these cells become cancerous. Additionally, epithelial cells are found in many body systems, highlighting the possibility that these findings may translate to other organs.

“It just shows that our bodies are imperfect in some ways and that we can generate these types of cells over the course of our lives,” Navin said.

“This has some pretty big implications, not just in breast cancer, but potentially for multiple types of cancer. It doesn’t necessarily mean that everyone is walking around with a precancer, but we need to think about ways to place larger studies to understand the implications for cancer development.

More information:

Yiyun Lin et al, Normal breast tissues harbor rare populations of aneuploid epithelial cells, Nature (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-08129-x

Provided by the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center

Quote: Healthy women have cells that resemble breast cancer, study finds (November 20, 2024) retrieved November 20, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.