Five decades of evolutionary response of D. subobscura to global warming in Europe. Credit: Nature Climate change (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41558-024-02128-6

UAB researchers have observed that rising temperatures and heatwave episodes over the past two decades have accelerated the presence of genetic variations that increase tolerance to high temperatures in populations of flies commonly found in European forests, Drosophila subobscura.

The evolutionary response was generated by an increase in the relative frequency of genetic variations already existing in individuals of the species, not by new variations. This therefore implies a rate of global warming that may have endangered species with lower levels of genetic variation.

Research into evolutionary responses to global warming is a challenging task. Studies on the subject are rare, and those that exist date back to the end of the last century.

In order to update the monitoring of these evolutionary responses in a context of increased global warming, researchers from the Department of Genetics and Microbiology of the UAB Francisco Rodríguez-Trelles Astruga and Rosa Tarrío Fernández studied the genetic variations of the fly Drosophila subobscura, much smaller than the housefly and commonly found in many European forests.

In this species, adaptation to climate is ensured by a type of genetic variation called chromosomal inversion polymorphism. Some inversions, a type of mutation that changes the orientation of genome segments, give the individual greater tolerance to cold temperatures, while others give it greater tolerance to heat.

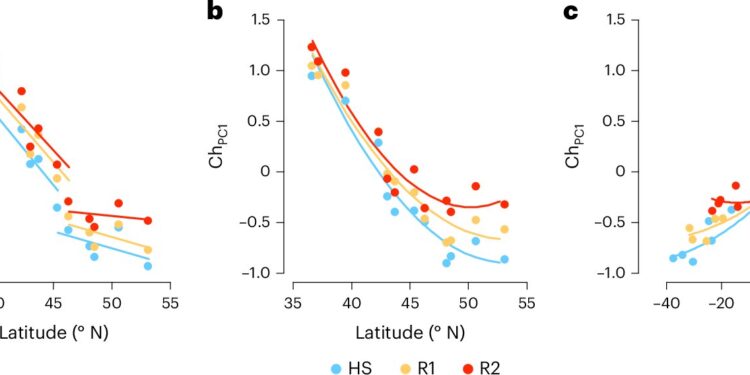

The results, obtained by UAB researchers and published in Nature Climate changeconfirm the results obtained in previous studies, which indicated that the proportion of inversions favouring heat tolerance increased and those favouring cold tolerance decreased. The study shows, for the first time, how this pattern has accelerated at an unprecedented speed over the last two decades in temperate Europe compared to the Mediterranean, following the impact of longer and more intense heat waves.

“The study began in 2015 and required hard work in the field and in the laboratory. We spent four years capturing samples of Drosophila subobscura in 12 locations in Europe at different latitudes. Local residents recounted their experiences of heat waves that they had never seen before. Later, we genetically characterized each of the samples in our laboratory at UAB,” explains Rodríguez-Trelles.

Researchers collected samples in Vienna, Austria; Leuven, Belgium; Lagrasse, Montpellier and Villars, France; Tübingen, Germany; Groningen, Netherlands; Leuk, Switzerland; Malaga, Punta Umbria, Riba-roja de Túria and Queralbs, Spain.

The 12 European sampling sites and their distribution relative to the Mediterranean-temperate climate transition zone. Credit: Nature Climate change (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41558-024-02128-6

Projections indicate that, unless greater efforts are made to mitigate global warming, central European populations of this species will become genetically indistinguishable from southern European populations by 2050.

According to Professor Rodríguez-Telles, coordinator of the UAB’s doctoral program in genetics, “this is unprecedented, because it is a model species that appears in textbooks as an example of how genetic variability helps adapt to climates that exist in different latitudes.”

The researchers did not detect any new inversions in the Drosophila subobscura samples, except for existing ones, leading them to conclude that the rate of new inversions is too slow to compensate for rising temperatures. This prospect is particularly worrisome in light of the growing number of insect species that are less able than Drosophila subobscura to adapt evolutionarily to global warming.

Plasticity and evolution, adaptation mechanisms in the face of rising temperatures

Human-caused global warming continues to worsen, and the adverse consequences are accumulating as science predicts. Organisms adapt to rising temperatures in two main ways: plasticity and evolution. While the former operates at the individual level, the latter operates at the population and species level. Examples of plasticity are in situ physiological acclimatization or moving to a location where the temperature is more tolerable.

When an increase in temperature exceeds the adaptive capacity of some individuals and there are no thermal shelters, the survival of the species depends on the genetically more thermotolerant individuals. This is when evolution is triggered, a response mechanism analyzed in this study.

“Observing evolutionary responses to global warming is both good news and bad news,” says Rodríguez-Trelles.

“This is good because it means that there are genetic variations that help to tolerate heat stress. Bad because it means the death of the unfortunate ones whose thermotolerant genetic variations are insufficient. Moreover, if global warming proceeds too quickly and lasts too long, even those with higher thermotolerance may succumb, leading to the extinction of the species,” he concludes.

More information:

Francisco Rodríguez-Trelles et al, Acceleration of the evolutionary response of Drosophila subobscura to global warming in Europe, Nature Climate change (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41558-024-02128-6

Provided by the Autonomous University of Barcelona

Quote:Global warming prompts rapid evolutionary response in fruit flies, study finds (2024, September 13) retrieved September 13, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.