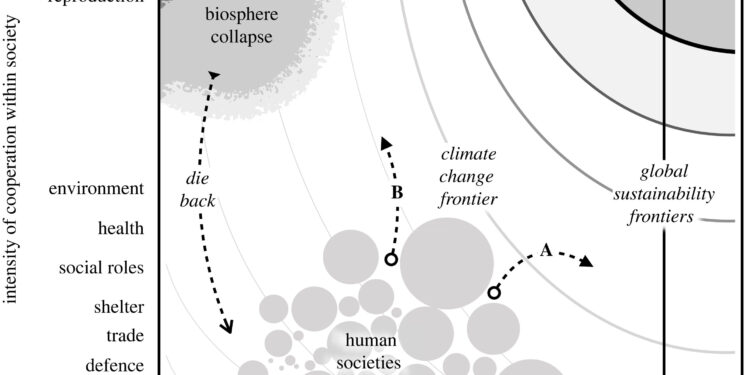

The dimensions of environmental management create an attractive landscape for long-term human evolution. Environmental sustainability challenges (curved boundaries) require a minimum level of cooperation in a society of a certain minimum spatial size. Alternative potential pathways lead humanity toward different long-term evolutionary outcomes. In Path B, competition between societies for common environmental resources creates cultural selection between groups for increasingly direct competition and conflict. Path A, increasing cooperation between societies, facilitates the emergence of global cultural traits to preserve shared environmental benefits. Credit: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences (2023). DOI: 10.1098/rstb.2022.0259

Central features of human evolution may be preventing our species from solving global environmental problems such as climate change, according to a recent study led by the University of Maine.

Humans have come to dominate the planet through tools and systems for exploiting natural resources that have been refined over thousands of years through the process of cultural adaptation to the environment. Tim Waring, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Maine, wanted to know how this process of cultural adaptation to the environment might influence the goal of solving the world’s environmental problems. What he discovered was counterintuitive.

The project sought to understand three fundamental questions: how human evolution worked in the context of environmental resources, how human evolution contributed to multiple global environmental crises, and how global environmental limits might alter the outcomes of human evolution in the future.

Waring’s team presented their findings in a new paper published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. Other authors of the study include UMaine alumnus Zach Wood and Eörs Szathmáry, a professor at Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest, Hungary.

Human expansion

The study explored how human societies’ use of the environment has changed over our evolutionary history. The research team studied changes in the ecological niche of human populations, including factors such as the natural resources they used, the intensity of their use, the systems and methods that emerged to use these resources, and the impacts environmental impacts resulting from their use.

This effort revealed a set of common patterns. Over the past 100,000 years, human groups have progressively used more types of resources, with more intensity, on larger scales, and with greater environmental impacts. These groups then often spread to new environments with new resources.

Global human expansion was facilitated by the process of cultural adaptation to the environment. This leads to the accumulation of adaptive cultural traits – social systems and technologies to help exploit and control environmental resources such as agricultural practices, fishing methods, irrigation infrastructure, energy technology and systems social resources to manage each of them.

“Human evolution is primarily driven by cultural change, which is faster than genetic evolution. This greater speed of adaptation has allowed humans to colonize all of the world’s habitable lands,” says Waring, an associate professor at the Senator George J. Mitchell Center of UMaine. for Sustainability Solutions and the School of Economics.

Furthermore, this process accelerates due to a positive feedback process: as groups become larger, they accumulate adaptive cultural traits more quickly, which provides more resources and enables faster growth.

“Over the past 100,000 years, this has been good news for our species as a whole.” Waring says, “but this expansion has depended on large amounts of available resources and space.”

Today, humans are also running out of space. We have reached the physical limits of the biosphere and claim most of the resources it has to offer. Our expansion is also catching up with us. Our cultural adaptations, particularly the industrial use of fossil fuels, have created dangerous global environmental problems that endanger our security and access to future resources.

Global limits

To see what these findings mean for solving global challenges such as climate change, the research team examined when and how sustainable human systems emerged in the past. Waring and his colleagues discovered two general trends. First, sustainable systems tend to develop and spread only after groups have struggled or failed to maintain their resources.

For example, the United States regulated industrial emissions of sulfur and nitrogen dioxide in 1990, but only after determining that they caused acid rain and acidified many bodies of water in the Northeast. This late action presents a major problem today as we threaten other global limits. When it comes to climate change, humans need to solve the problem before we cause a crash.

Second, researchers have also found that strong environmental protection systems tend to solve problems within existing societies, not between them. For example, managing regional water systems requires regional cooperation, regional infrastructure and technologies, and these arise from regional cultural evolution. The presence of companies of the right scale is therefore a critical limiting factor.

Effectively tackling the climate crisis will likely require new global regulatory, economic and social systems that generate greater cooperation and authority than existing systems like the Paris Agreement. To establish and operate these systems, humans need a functioning social system for the planet, which we do not have.

“One of the problems is that we don’t have a coordinated global society that could implement these systems,” Waring says. “We only have sub-global groups, which probably won’t be enough. But you can imagine cooperative treaties to address these common challenges. So that’s the easy problem.

The other problem is much worse, Waring says. In a world full of sub-global groups, the cultural evolution of these groups will tend to solve the wrong problems, benefiting the interests of nations and corporations and delaying action on shared priorities. Cultural evolution between groups would tend to exacerbate competition for resources and could lead to direct conflict between groups and even human decline on a global scale.

“This means that global challenges such as climate change are much more difficult to solve than previously thought,” says Waring. “It’s not just that this is the hardest thing our species has ever done. It absolutely is. The bigger problem is that central elements of human evolution are likely harming our ability to solve them. To solve the world’s collective challenges, we must swim against the tide.”

Look forward to

Waring and his colleagues believe their analysis can help determine the future of human evolution on a limited Earth. Their paper is the first to propose that human evolution may oppose the emergence of global collective problems and that additional research is needed to develop and test this theory.

Waring’s team proposes several applied research efforts to better understand the drivers of cultural evolution and explore ways to reduce global environmental competition, considering how human evolution works. For example, research is needed to document the patterns and strength of human cultural evolution in the past and present. Studies could focus on past processes that led to human domination of the biosphere, as well as how cultural adaptation to the environment occurs today.

But if the broad outlines prove correct and human evolution tends to oppose collective solutions to global environmental problems, as the authors suggest, then some very pressing questions will need to be answered. This includes whether we can use this knowledge to improve the global response to climate change.

“There is of course hope that humans can solve climate change. We have built cooperative governance before, but never like this: in a rush on a global scale,” Waring says.

The growth of international environmental politics offers some hope. Examples of success include the Montreal Protocol to limit ozone-depleting gases and the global moratorium on commercial whaling.

New efforts should include the promotion of more intentional, peaceful, and ethical systems of mutual self-restraint, particularly through market regulations and enforceable treaties, which ever more closely bind human groups across the planet into a functional unit .

But this model might not work for climate change.

“Our paper explains why and how building cooperative governance on a global scale is different and helps researchers and policymakers be more clear-eyed about how to work towards global solutions,” says Waring.

This new research could lead to a new policy mechanism for addressing the climate crisis: altering the process of adaptive change among businesses and nations can be a powerful way to address global environmental risks.

As for whether humans can continue to survive on a limited planet, Waring says: “We have no solution to this idea of a long-term evolutionary trap, because we barely understand the problem. that’s right, we need to study this much more carefully. »

More information:

Timothy M. Waring et al, Processes characteristic of human evolution brought about the Anthropocene and may hinder its global solutions, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences (2023). DOI: 10.1098/rstb.2022.0259

Provided by University of Maine

Quote: Evolution could prevent humans from solving climate change, researchers say (January 2, 2024) retrieved January 2, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.