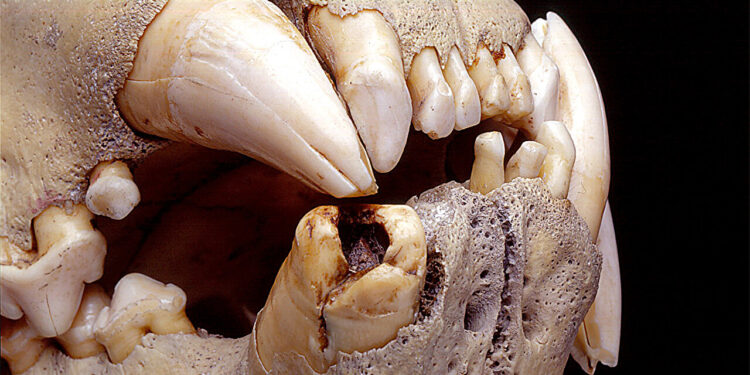

Lions’ teeth have been damaged during their lives. Study co-author Thomas Gnoske discovered thousands of hairs embedded in the exposed cavities of broken teeth. Credit: Photo Z94320, courtesy of the Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago

In 1898, two male lions terrorized a bridge builders’ camp on the Tsavo River in Kenya. The lions, massive and without manes, crept into the camp at night, pillaged the tents and snatched their victims. Tsavo’s notorious “man-eaters” killed at least 28 people before Lt. Col. John Henry Patterson, the civil engineer in charge of the project, shot them dead. Patterson sold the lion remains to the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago in 1925.

In a new study, Field Museum researchers collaborated with scientists at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign for an in-depth analysis of hairs carefully extracted from lions’ broken teeth. The study used microscopy and genomics to identify some of the species consumed by lions. The results are reported in the journal Current biology.

The initial discovery of the hairs occurred in the early 1990s, when Thomas Gnoske, collections manager at the Field Museum, found the lion skulls in a warehouse and examined them for signs of what they had consumed .

He was the first to determine that they were older adult males, although they were without manes. He was also the first to notice that thousands of broken and compacted hairs had accumulated in the exposed cavities of the lions’ damaged teeth over the course of their lives.

In 2001, Gnoske and Julian Kerbis Peterhans, a professor at Roosevelt University and assistant curator at the Field Museum, first reported the damaged state of the teeth – which they said may have contributed to the predation of humans by the lions – and the presence of embedded hairs. in broken and partially healed teeth. Preliminary analysis of some of the hairs suggested they came from elk, impala, oryx, porcupines, warthogs and zebras.

In the new study, Gnoske and Peterhans facilitated a new examination of certain hairs. Co-authors Ogeto Mwebi, Senior Research Scientist at the National Museums of Kenya; and Nduhiu Gitahi, a researcher at the University of Nairobi, conducted the microscopic analysis of the hair.

Alida de Flamingh, a postdoctoral researcher at U of I, conducted a genomic investigation of hair with U of I anthropology professor Ripan S. Malhi. They focused on a separate sample of four individual hairs and three tufts of hair extracted from the lions’ teeth.

Malhi, de Flamingh and their colleagues are developing new techniques to learn about the past by sequencing and analyzing ancient DNA preserved in biological artifacts. Their work in partnership with indigenous communities has yielded much insight into human migration and the pre- and post-colonial history of the Americas.

They contributed to the development of tools to determine the species and geographic origins of current and ancient tusks of African elephants. They advanced their efforts to isolate and sequence DNA from museum specimens and traced the migration and genomic history of dogs in the Americas.

In his current work, de Flamingh first looked for and discovered familiar signs of age-related degradation in what remained of the nuclear DNA in the lions’ tooth hairs.

“To establish the authenticity of the sample we are analyzing, we look to see if the DNA exhibits these patterns that are typically found in ancient DNA,” she said.

Once the samples were authenticated, de Flamingh focused on the mitochondrial DNA. In humans and other animals, the mitochondrial genome is inherited from the mother and can be used to trace matrilineages over time.

There are several benefits to focusing on mtDNA in hair, researchers say. Previous studies have shown that hair structure preserves mtDNA and protects it from external contamination. MtDNA is also much more abundant than nuclear DNA in cells.

“And because the mitochondrial genome is much smaller than the nuclear genome, it is easier to reconstruct in potential prey,” de Flamingh said.

The team built a database of mtDNA profiles of potential prey species. This reference database was compared to mtDNA profiles obtained from hair. The researchers considered the species suggested in the previous analysis and those known to be present in Tsavo at the time the lions were alive.

Researchers have also developed methods for extracting and analyzing mtDNA from hair fragments.

“We were even able to obtain DNA from fragments shorter than the nail on your little finger,” de Flamingh said.

“Traditionally, when people want to get DNA from hair, they focus on the follicle, which contains a lot of nuclear DNA,” Malhi said. “But these were fragments of hair shafts that were over 100 years old.”

This effort yielded a treasure trove of information.

“DNA analysis of the hair identified giraffe, human, oryx, waterbuck, wildebeest and zebra as prey, as well as hairs from lions,” the researchers reported .

The lions were found to share the same maternally inherited mitochondrial genome, supporting early reports theorizing that they were siblings. Their mtDNA also matched an origin in Kenya or Tanzania.

The team found that the lions had consumed at least two giraffes, as well as a zebra likely native to the Tsavo region.

The discovery of wildebeest mtDNA was surprising because the closest wildebeest population in the late 1890s was about 50 miles away, the researchers said. Historical reports, however, note that the lions left the Tsavo area for about six months before resuming their rampage on the bridge builders’ camp.

The absence of buffalo DNA and the presence of a single buffalo hair, identified by microscopy, was surprising, de Flamingh said. “We know from what Tsavo lions eat today that buffalo are their favorite prey,” she said.

“Colonel Patterson kept a handwritten field journal during his time at Tsavo,” said Kerbis Peterhans. “But he never recorded in his journal seeing buffalo or native cattle.”

At the time, cattle and buffalo populations in this part of Africa were being devastated by rinderpest, a highly contagious viral disease introduced to Africa from India in the early 1880s, Kerbis Peterhans said.

“This has virtually wiped out livestock and their wild relatives, including Cape buffalo,” he said.

The human hair mitogenome has a wide geographic distribution and scientists declined to describe or analyze it further for the present study.

“There may still be descendants in the area today and to practice responsible and ethical science, we use community-based methods to extend the human aspects of the larger project,” they wrote.

The new results represent a significant expansion in the type of data that can be extracted from skulls and hairs of the past, the researchers said.

“We now know that we can reconstruct complete mitochondrial genomes from fragments of lion hairs that are more than 100 years old,” de Flamingh said.

There were thousands of hairs embedded in the lions’ teeth, compacted over the years, the researchers said. Further analysis will allow scientists to at least partially reconstruct the lions’ diet over time and perhaps determine precisely when their habit of preying on humans began.

More information:

Compacted hairs from broken teeth reveal historic lion food prey, Current biology (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2024.09.029. www.cell.com/current-biology/f… 0960-9822(24)01240-5

Provided by University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Quote: Hidden in the teeth: DNA study reveals these 19th century lions fed on humans and giraffes (October 11, 2024) retrieved October 11, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.